The story is basically me looking back over the past few years and wondering what the heck was I thinking, and how many times did I guess wrong, and how many times did I change my mind about equipment and process. I actually opened some of the cabinet doors in my work area to discover each great idea that never got out of its blister pack and shipping carton. I’ve determined it cost about 2 bucks in equipment to handload, so where did I spend $3.2 million? the following illustrates some of my tendencies toward excess. But first…

Handloading was borne out of necessity. With factory ammo in short supply, uniquely dimensional cartridges common place, handloading was required in support of hunting, war and general self defense. Even the U.S. Government got into the handloading act in 1866 when they provided field reloading tools with the introduction of the .50-70 Govt. I’m pretty sure handloading wasn’t traumatic to these folks as they were experienced with muzzle loading rifles and cap and ball revolvers, not a steady diet of factory ammo like modern “Which way are the woods?” man. They metered powder, seated projectiles to a critical depth and finished up with a percussion cap routinely. Pictured left, the difference between muzzle loading and handloading is primarily the container that holds the components.

Handloading was borne out of necessity. With factory ammo in short supply, uniquely dimensional cartridges common place, handloading was required in support of hunting, war and general self defense. Even the U.S. Government got into the handloading act in 1866 when they provided field reloading tools with the introduction of the .50-70 Govt. I’m pretty sure handloading wasn’t traumatic to these folks as they were experienced with muzzle loading rifles and cap and ball revolvers, not a steady diet of factory ammo like modern “Which way are the woods?” man. They metered powder, seated projectiles to a critical depth and finished up with a percussion cap routinely. Pictured left, the difference between muzzle loading and handloading is primarily the container that holds the components.

Necessity handloading, as a life or death necessity, gave way to recreational and economical handloading in the 1940’s and has persisted to varying degrees of popularity and activity since. It is difficult to tell if we are in the midst of popularity spike or in the midst of a competitive market frenzy. There has been a steady stream of new component introductions, die sets are available by the time new factory cartridges are released and the sale of specialized test equipment has steadily increased in visibility in publications as well as at the range. While there are more specialized tools on the market geared toward the precision handloader, and the effects of electronics has made its way into powder scales and dispensing systems, there appears to be little evolution or innovation in the basic handloading tools other than material and manufacturing cost reduction. Early shooters would not be lost around most modern reloading hardware.

Reloading or Handloading….

Joe, what is the difference between reloading and handloading ? Thank you stranger, glad you asked. If the subject of the effort is $3 a box .30-30 WCF ammo for use during local deer season, you are probably reloading. If you’re a fancy lad, and the subject of the effort is $20 per round 577 Nitro Express ammo destined for use on a $50,000 safari, you are no doubt handloading. Kidding, just kidding….really. Reloading infers the recycling or reuse of cartridge casings from expended ammo. Handloading infers the assembly of a cartridge, first use or repeat use of brass, and possibly infers an original combination of components assembled with great care. So you can reload your spent brass, reload your reloads, reload your handloads, and handload your reloads, but you can’t reload new brass. Never know, someone might ask. No, nope, they probably won’t.

I would advance the proposition that there are four basic reasons for handloading:

-

Savings – Modest for inexpensive factory ammo, huge for premium and large capacity ammo.

-

Unique combinations – Assemble components not readily available in factory loaded form.

-

Performance – Optimize component selection and assembly for a specific firearm and purpose.

-

Enjoyment – Handloading can be fun and challenging.

Savings – Under some circumstances, it may make little economic sense to handload. Savings derived from handloading two boxes of centerfire ammo would not offset the expenditure for reloading equipment, components and other related supplies. Reloading a box of spent 460 Weatherby brass for a savings of $80, sounds like a huge savings, but the savings would pale in comparison to a handloading error induced misfire that resulted in an unsuccessful $20,000 safari. There are, however, many circumstances where handloading makes a great deal of sense. Big bullets cost big money and at .458″, the .45-70 and 458 Winchester magnum can be costly to shoot. Use of manufacturer bulk bullets and quality cast bullets alone can reduce the cost of even 20 rounds by $8. It’s relatively easy to spend $30 – $50 per box for premium 7mm Remington Magnum ammo, while a box can be reloaded to similar levels of components and performance for only $10. 416 Weatherby factory ammo runs between $90 and $100 per box of 20 rounds, 338-378 Weatherby about $10 less. I can reload 20 cartridges with premium bullets for $20 and $10 per box respectively. Handgunners, who may shoot more frequently and in greater volume than long gunners, can replace 20 round boxes of Speer Gold Dot 45 ACP ammo at $13, with reloads with the same Gold Dot bullets for $3.00. A similar benefit applies to basically any handgun ammo beyond the .380 ACP.

Savings – Under some circumstances, it may make little economic sense to handload. Savings derived from handloading two boxes of centerfire ammo would not offset the expenditure for reloading equipment, components and other related supplies. Reloading a box of spent 460 Weatherby brass for a savings of $80, sounds like a huge savings, but the savings would pale in comparison to a handloading error induced misfire that resulted in an unsuccessful $20,000 safari. There are, however, many circumstances where handloading makes a great deal of sense. Big bullets cost big money and at .458″, the .45-70 and 458 Winchester magnum can be costly to shoot. Use of manufacturer bulk bullets and quality cast bullets alone can reduce the cost of even 20 rounds by $8. It’s relatively easy to spend $30 – $50 per box for premium 7mm Remington Magnum ammo, while a box can be reloaded to similar levels of components and performance for only $10. 416 Weatherby factory ammo runs between $90 and $100 per box of 20 rounds, 338-378 Weatherby about $10 less. I can reload 20 cartridges with premium bullets for $20 and $10 per box respectively. Handgunners, who may shoot more frequently and in greater volume than long gunners, can replace 20 round boxes of Speer Gold Dot 45 ACP ammo at $13, with reloads with the same Gold Dot bullets for $3.00. A similar benefit applies to basically any handgun ammo beyond the .380 ACP.

Generally speaking, the savings from handloading is derived from reusing brass a number of time, and excluding the additional labor, material, overhead and profit of factory assembled ammunition. I use to buy factory ammo, shoot it, then reload it. Now I just buy brass, new or once fired, and skip the costly step. AS an example, I can buy once fired 223 Remington brass for 5¢ each, and safely reload each 10 times. 5¢ divided by 10, the number of times I can reuse the brass, means half a penny a piece per case. 1 lb, or 7,000 grains of smokeless powder runs about $16, each case uses about 26 grains, so about 6¢ for powder. A primer adds about another 1 1/2¢; a total so far of 8¢ per round. Now I can stuff in a 40 grain Hornady V Max for another dime and we conclude at 18¢ per round or $3.60 per box of 20. I could also load a 45 grain Remington soft point at 6¢ for $3.20 per box of 20. Hornady factory varmint ammo is $15 per box of 20 through discount online shopping. Remington ammo is $17 per box of 20 so there is $10 ~ $15 worth of savings per box even for this small inexpensive cartridge.

Cost of brass/number of times used + cost of powder+cost of primer+cost of bullet

The only thing to keep in mind is the investment made in equipment. For $270, you could buy a Lyman Crusher 2 Single Stage Press Expert Kit or similar that contains every tool needed to reload with the exception of a $25 set of cartridge specific dies, and be off and running. You could do the same with a Lee press for under $80. Based on the saving potential, you would have to load 10~15 boxes of 223 Remington ammo to cover the investment of equipment and begin showing actual savings. While the cost of equipment pretty much remains the same, the savings differs based on the cartridge.

257 Weatherby Magnum – .90 / 10 = .09+.18+.02+.13= 42¢ or $8.40 per box. Factory ammo is $40 per box, so $31.60 per box in savings and the equipment is paid for in 8.5 boxes. I can recover almost $80 per box of 416 Weatherby; 3 boxes for payback. In reality, I load for all of these and my equipment was covered in the first 30 days of use.

Unique combinations – Handloading generated savings may be irrelevant. When I feel the need to create a cartridge with poor sectional density, minimal bullet availability and no practical purpose, I can only rely on handloading equipment and odd combinations of components to provide what no sane manufacturer would. Sometimes, just sometimes, one of these weird creations can be optimized to serve a useful purpose. My 358-378 RG isn’t much with lightweight and middle weight .358″ bullets, but with a 310 grain Woodleigh or 280 grain A Frame bullets it will absolutely flatten jackrabbits, assuming they are not a protected specie. My 17-357RG may sound like “What the heck was he thinking?” fodder, but I have a 2 lb, 3200 fps varmint shooting handgun. In a more general sense, I like CCI Primers, they are reliable and seem to produce a little more velocity with heavy charges. I like heavy Woodleigh and Swift bullets for my .338 and .358 caliber rifles, and GS Custom banded bullets for my .257″ guns. I like Alliant Powder most of the time, Hodgdon powder some of the time, and four or five other brands every once in a while. Handloading affords me the opportunity to assemble these components into optimal assemblies, and I can assemble in quantities I need, when I need them.

Unique combinations – Handloading generated savings may be irrelevant. When I feel the need to create a cartridge with poor sectional density, minimal bullet availability and no practical purpose, I can only rely on handloading equipment and odd combinations of components to provide what no sane manufacturer would. Sometimes, just sometimes, one of these weird creations can be optimized to serve a useful purpose. My 358-378 RG isn’t much with lightweight and middle weight .358″ bullets, but with a 310 grain Woodleigh or 280 grain A Frame bullets it will absolutely flatten jackrabbits, assuming they are not a protected specie. My 17-357RG may sound like “What the heck was he thinking?” fodder, but I have a 2 lb, 3200 fps varmint shooting handgun. In a more general sense, I like CCI Primers, they are reliable and seem to produce a little more velocity with heavy charges. I like heavy Woodleigh and Swift bullets for my .338 and .358 caliber rifles, and GS Custom banded bullets for my .257″ guns. I like Alliant Powder most of the time, Hodgdon powder some of the time, and four or five other brands every once in a while. Handloading affords me the opportunity to assemble these components into optimal assemblies, and I can assemble in quantities I need, when I need them.

Performance – There is a great myth I see expressed too frequently, “Factory ammo is so good these days, you could not match its performance with handloads of greater accuracy or higher velocity”. The day I started handloading, I stopped buying factory ammo that wouldn’t group 1 1/2″ – 2″ in most of my rifles, and started getting sub MOA out of just about any gun I owned. If I am feeling lazy, pressed for time, or just shooting to make noise, I will grab a box of cheap white or yellow box factory ammo and blast away, if I am interested in working down to dime size groups and eking out the last bit of velocity, I handload. I can reduce muzzle flash in my handguns, boost 45 ACP performance to impressive levels, put holes through tree trunks with my Ruger .45 LC, and make my 416 Weatherby shoot incredibly flat and with great accuracy. I can also download my .45-70 for plinking, or upload for bear. I have found opportunities to improve performance of a cartridge and firearm significantly with just a little handloading experimentation.

Performance – There is a great myth I see expressed too frequently, “Factory ammo is so good these days, you could not match its performance with handloads of greater accuracy or higher velocity”. The day I started handloading, I stopped buying factory ammo that wouldn’t group 1 1/2″ – 2″ in most of my rifles, and started getting sub MOA out of just about any gun I owned. If I am feeling lazy, pressed for time, or just shooting to make noise, I will grab a box of cheap white or yellow box factory ammo and blast away, if I am interested in working down to dime size groups and eking out the last bit of velocity, I handload. I can reduce muzzle flash in my handguns, boost 45 ACP performance to impressive levels, put holes through tree trunks with my Ruger .45 LC, and make my 416 Weatherby shoot incredibly flat and with great accuracy. I can also download my .45-70 for plinking, or upload for bear. I have found opportunities to improve performance of a cartridge and firearm significantly with just a little handloading experimentation.

Enjoyment – What constitutes enjoyment is pretty subjective. I like the organized flow of a cartridge work up and load development. I like the preciseness of data tracking, measurement and using precision tools and machinery. I like to see the influence of my efforts, the changes I make and approaches I take, expressed as objective results. In short, I am a married man with children, so any time I can feel in command, stand as the captain of my ship, be the chief honcho, or a major poobah, it is a wonderful and unique experience. I mostly load in moderate volume. Production doesn’t hold a potential for great excitement; the work is repetitive, high sustainable levels of concentration are required and, by intent, nothing out of the ordinary occurs. It is only my enthusiasm for the step following handloading, shooting, that gets me through any production effort. There is socialization in handloading, but it is cliquish in nature; people of similar handloading interests seem to congregate around specific manufacturers of equipment. Manufacturers producing single stage and turret presses of quality manufacturer tend to draw the precise folks, the experimenters and the new cartridge and wildcat loaders. Manufacturers producing semi automated and progressive presses get the folks who like to talk about output; tons and tons of 308 Winchester and 223 Remington reloads.

Purchasing Handloading Equipment – The Devil’s Tools

I do not know why the prospect and act of buying handloading equipment reduces most people to putty brains, me included. It just seems the first step in putting together equipment and supplies for the purpose of assembling hazardous and explosive material should not a trip to an Internet message board to ask the question, “I am new to handloading. How much powder should I put in my 308 cartridges?”. To which a guy who calls himself Popeye22 will answer, “Just fill it up with whatever you got”. Buy a book you cheap bastard. If you can spend $3.2 million on a Dillon press, why not pop for $30 to buy a life saving device? Remember, the guy at the shooting spot next to you, and your potentially exploding rifle, is probably me. Good manuals will explain the purpose and use of all essential loading equipment, the handloading process, safety in loading and handling materials, and safe load data. I can’t help but chuckle, or at least snort, when I see Popeye22 explain to unknowing minions how to use before and after case head measurement to check for an excessive pressure condition. Contrary to being arcane information, this is standard technique published in virtually every quality handloading manual. Did I mention Sierra? Think of the $30 expenditure as your opportunity to become Popeye23.

I do not know why the prospect and act of buying handloading equipment reduces most people to putty brains, me included. It just seems the first step in putting together equipment and supplies for the purpose of assembling hazardous and explosive material should not a trip to an Internet message board to ask the question, “I am new to handloading. How much powder should I put in my 308 cartridges?”. To which a guy who calls himself Popeye22 will answer, “Just fill it up with whatever you got”. Buy a book you cheap bastard. If you can spend $3.2 million on a Dillon press, why not pop for $30 to buy a life saving device? Remember, the guy at the shooting spot next to you, and your potentially exploding rifle, is probably me. Good manuals will explain the purpose and use of all essential loading equipment, the handloading process, safety in loading and handling materials, and safe load data. I can’t help but chuckle, or at least snort, when I see Popeye22 explain to unknowing minions how to use before and after case head measurement to check for an excessive pressure condition. Contrary to being arcane information, this is standard technique published in virtually every quality handloading manual. Did I mention Sierra? Think of the $30 expenditure as your opportunity to become Popeye23.

Once you get the gist of what handloading is about, along with the various techniques and processes required, you have to make a key decision – Do you want to make high quality to excellent ammunition, or are you willing to live with more moderate quality goals in pursuit of exceptionally high volume? At the risk of annoying those pesky “blue” people, I would state categorically that amateur volume production equipment, when used as intended, does a lousy job of reloading. I’m not suggesting this is the result of substandard equipment, but rather a byproduct of the forced incorrect sequence of assembly the equipment follows when processing spent cases, particularly when utilizing automated case feeding systems.

Once you get the gist of what handloading is about, along with the various techniques and processes required, you have to make a key decision – Do you want to make high quality to excellent ammunition, or are you willing to live with more moderate quality goals in pursuit of exceptionally high volume? At the risk of annoying those pesky “blue” people, I would state categorically that amateur volume production equipment, when used as intended, does a lousy job of reloading. I’m not suggesting this is the result of substandard equipment, but rather a byproduct of the forced incorrect sequence of assembly the equipment follows when processing spent cases, particularly when utilizing automated case feeding systems.

Cases need to be thoroughly cleaned and inspected, and cleaning can’t be accomplished with a spent primer in place. So the sequence is decap, then clean. Cases need to be trimmed to proper and uniform length for a seating die to work correctly, unfortunately, case dimensions are not stable as a base reference point until after resizing. A single stage, single or multiple die station, press, permits the proper sequence to be followed, a progressive press does not. In fact, for a progressive press to pay off in output capacity, it depends on a spent and still primed case being fed into the press and the sequence of assembly not interrupted until the round is finished. No controversy, just a statement of fact. The use of new brass solves the dirty primer pocket problem but, since new brass should be passed through a sizing die before loading, the potential for incorrect trim length remains. Press mounted powder dispensers are another weak spot, even with alarms and devices designed to flag shot throws or double charges. Mechanical powder dispensers were generally made for metering ball powder, not the long extruded type so common in handloading for the past 20 years. In use, dispensers are sensitive to vibration, handle effort and velocity as well as powder density in the hopper. Throw 50 charges in the 30 grain and above range and scale check; I’d bet the results will park your eyebrows up next to your hairline, or at least where your hairline use to be. So if you don’t mind loading dirty cases, of indeterminist length, with varying powder charges in large quantity, progressive presses are definitely the way to go. I just ate a half a cracker, put on my glasses, and realized the remaining half is covered with odd rust colored spores. Hmm….

For those of you remaining

OK, if you’ve survived the suggestion of buying a book and not wasting your money on high speed automated loading of 100 rounds of ammo per month, you may as well hear some more. The basis for equipment selection is really quite simple; once you buy it, what the heck are you going to do with it? A would-be handloader needs to figure out what cartridges will be loaded, at the onset and in the near future, and to what quantity and level of quality they will be loading each. Typically, drawn by the lore of a basement ego ammo factory, people tend to overstate the variety of cartridges they will handload (well I might decide to buy a 22-300 Vundervopper), then multiply the quantity of each by 1,000 and determine that each handload will be of bench rest competition quality. No, I don’t know understand the dynamics of this scenario, but perhaps it is a pitiful cry for help from people who don’t how to express their handloading enthusiasm in any form other than volume – although I have seen some use terminology like “bullet to case longitudinal concentricity”. The important thing is, don’t BS yourself by trying to reach too far to cover extreme eventualities. By the same token, not building in enough slack to account for probable future combinations can also result in a less than thrilling outcome. In handloading, you can’t even decide to “just buy the best” to cover everything, as the most expensive equipment is typically the least flexible in use and very limited in application. You wouldn’t want to buy a Dillon Super 1050 Auto-indexing system set up if you planned on handloading modest quantities of magnum rifle cartridges, and you wouldn’t to want to buy an RCBS Rock Chucker if you intend to handload 5,000 rounds of .45 ACP or 308 Winchester ammo every day.

At the center of the equipment selection process, the piece that will set the stage for most of your other equipment requirements is the press. Presses are made in a number of variations, however, they are generally categorized as: single station, turret, manually indexed progressive and auto indexed progressive. As stated previously, it is my unpopular opinion that progressive presses lead to bad reloading habits for most people and, by design, trade off quality for speed. As bad at that sounds, under some circumstances the approach may be reasonable; depending upon the type of cartridge, the degree of quality sacrificed and the gain in speed. I could probably live with a few reloads of 45 ACP and similar ammo for non critical use, not self defense or combat, without cleaning primer pockets each time. I would probably not worry about case stretch and trimming, particularly if I needed and could load 1000 plus rounds an hour.

I frequently handload a wide variety of cartridge in short quantities, with a mix of components within each batch. Subsequently, I go through a lot of set ups and change equipment and dies over routinely. A long run to me a couple hundred rounds of a favorite .223 Remington load, or 4 boxes of 338-378 Weatherby. I do handload handgun ammo; 45 ACP, 40 S&W, 357 SIG, 45 Colt, 44 Magnum. I may knock off a few hundred rounds of the first three, perhaps a box or two of the remaining. I may also go months without reloading any of these. This means I am not a candidate for auto progressive, or fixed sequenced manually indexed progressive equipment. When the runs are short, I generally use a single stage press, when I have a larger run, particularly with mixed cartridge types, I use a turret press for speed and convenience.

Single Stage – Single Station Presses

Single station presses hold one die, and have one cartridge locating position. Dies are changed as the handloading process progresses. Representative models are: CH4D Champion Press, Forster Co-Ax, Hood Press, Hornady Lock-N-Load Classic, Lee Classic Cast Press, and Lyman Crusher II.RCBS offers several single stage presses for different applications: Ammo Master, Partner, Reloader Special – 5 and the popular Rock Chucker. Redding, another industry mainstay produces the Boss, Big Boss and Ultramag single stage presses.

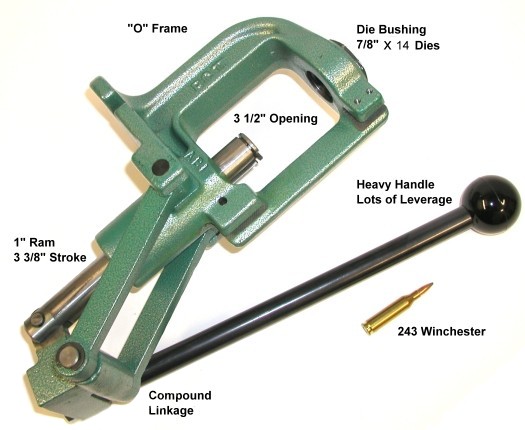

The Rock Chucker is a typical single station “O” frame design, which means the upper frame that locates the die is cast in a one piece closed loop for maximum strength. There are also “C” type presses, open on one side, like the Redding Ultramag and Forster Co-Ax. and hybrids like the Ammo Master with a die plate located above the press body with three steel struts. The Rock Chucker die station is fit with a bushing to provide standard die size 7/8″ x 14 threads when installed, or the bushing may be removed for use of larger size dies, or the press may be fit with a Piggy Back 4 accessory that converts the Rock Chucker to a 5 station manual indexing progressive press. “O” type presses have one fixed die station and one fixed shell holder position. They are made to perform one process step at a time; precisely and consistently.

When reviewing competing presses there are a few areas worth investigation. Long cartridges require a lot of room above the shell holder and below the die, the Rock Chucker II pictured above has 3 7/8″ of clearance, the newer Rock Chucker Supreme model clearance was extended to 4″. The ram is a beefy 1″ in diameter, the compound linkage increases mechanical advantage and the handle is huge – all of that means a lot of leverage, which really comes in handy when full length resizing large case cartridges and a much smoother action when seating bullets or crimping. This press is cast iron and weighs over 20 lbs, another plus when round to round consistency of process is required. By comparison, the Hornady Lock-N-Load Classic of alloy construction is not as rigid, requires more effort in use and weighs only 12 lbs. The cost of the two presses in retail outlets is virtually identical. The expensive press in the mix identified above is the CH4D Champion, approximately $250 in bare bones form. The least costly are the aluminum framed Lee Reloader “C” type at $18 or Lee Challenger at $29 at discount retail outlets. I think there are three good comparable presses in the pile: Rock Chucker Supreme, Big Boss and Lyman Crusher II. They are all sturdy cast iron, have large opening and long strokes for large cartridges and sell at a comparable price $90~$110.

Lock-N-Load and Snap In-Out Die changing and similar features are mostly solutions in search of a problem. When equipment remains essentially unchanged in function for a number a decades companies will dig for differentiation in a competitive market place. I personally own a thousand or so Lock-N-Load bushings I keep in a box under my handloading bench. Once wrapped around all of my dies for competing in the quick draw die change events, I came to the realization it actually took longer to install and setup L-N-L bushed dies then standard dies so I stopped using them. There are too many variations in brass and bullet types to be able to pop in a bushed die and start working. If there is a net time savings in the use of quick change die schemes, it would be measures as an exception and in a few brief seconds.

Lock-N-Load and Snap In-Out Die changing and similar features are mostly solutions in search of a problem. When equipment remains essentially unchanged in function for a number a decades companies will dig for differentiation in a competitive market place. I personally own a thousand or so Lock-N-Load bushings I keep in a box under my handloading bench. Once wrapped around all of my dies for competing in the quick draw die change events, I came to the realization it actually took longer to install and setup L-N-L bushed dies then standard dies so I stopped using them. There are too many variations in brass and bullet types to be able to pop in a bushed die and start working. If there is a net time savings in the use of quick change die schemes, it would be measures as an exception and in a few brief seconds.

Turret Presses

A turret press is a pretty good compromise when it comes to quantity, laziness and quality of finished product, a piece of equipment I most frequently use. The unit pictured is the RCBS Turret press, however, Redding, Lyman and Lee all make competing models. Quality and prices vary, running from the $85 4 hole Lee Turret Press deluxe kit, to the 6 hole $125 Lyman T-Mag and $165 RCBS units, to the $190 T-7 Redding.

All manufacturers offer additional heads as accessories for holding pre-set die sets, the 7 hole Redding might make sense for a universal decapping or lube die, or a mechanical powder dispenser. Additional press heads are a low of $8 for the Lee press, $28 for the Lyman unit, $36 for the RCBS, and $50 for the Redding. I believe the Lyman, RCBS and Redding are a toss up in regard to quality and capability. They are all heavy cast iron, the Lyman and RCBS weigh about 20 lbs, the Redding unit at close to 30 and all are supplied with a basic priming system and spent primer catcher. If I were to make the purchase today, I might be tempted to select the Redding with it’s 4 3/4″ clearance and 7 hole head, but I’ve had no problem loading long cartridges my RCBS press. I typically load three heads; two sets of straight wall dies, three sets of bottle neck and full of multi step forming does for a wildcat, then I change out dies when necessary. Change out takes a minute or two, dies or heads, and the turret rotates in either direction for lefthanders and people living in the U.K. Unlike a progressive press where multiple cartridges are processed in one shot, exertion is low with a single cartridge location and any sequence of operation can be selected. All other accessories, shell holders, dies and powder dispensers used with a turret press are the same as single stage – single station presses.

The other stuff and the real money…

Shell Holders

Unless you have committed to an auto progressive press, in which case you would not be reading this, the rest of the equipment sources are up for grabs….with the exception of shell holders. I tried buying shell holders to match die manufacturers in hopes of maintaining some theoretical dimensional relationship between the two, rather than selecting holders based on the press manufacturer, but the results were mixed. Mostly, the shell holders didn’t fit, particularly Hornady holders in RCBS presses, but there also seemed to nothing to gain in this arrangement. Now I match shell holders to press and used dies from a variety of manufacturers.

Unless you have committed to an auto progressive press, in which case you would not be reading this, the rest of the equipment sources are up for grabs….with the exception of shell holders. I tried buying shell holders to match die manufacturers in hopes of maintaining some theoretical dimensional relationship between the two, rather than selecting holders based on the press manufacturer, but the results were mixed. Mostly, the shell holders didn’t fit, particularly Hornady holders in RCBS presses, but there also seemed to nothing to gain in this arrangement. Now I match shell holders to press and used dies from a variety of manufacturers.

Dies

Some tools are necessary for functional and safety considerations, some are nice to have but perhaps superfluous and other, for competitive shooters, are required. Virtually any dies of 7/8″x14 size can be utilized in virtually any press. Die selection, like presses, is mostly determined by application. Basic level dies are plenty accurate, the next step up under a variety of brand names have micrometer adjustment of bullet seating dies. $20~$30 will get you a perfectly good set of handloading does for non-belted centerfire cartridges from any of the major suppliers; Forster, Hornady, Lyman, RCBS, and Redding. The next level up with micrometer adjustment, bushed dies, top load bullet seating, etc. can be had in the range of $75~$139; the low end of this range is pretty terrific with broader applications. I think the best die value on the market today, and one of the easiest to use when it comes to bullet seating and concentric ammo is the Hornady New Dimensionwith it’s floating bullet alignment design.

Perhaps as a cost reduction effort, but one that is beneficial to handloaders, Hornady went to a more or less generic die body. The cartridge specific bushing or sleeve (1) floats in the body, prevented from falling out by a retaining clip. When a bullet is placed in the case mouth and the case is lifted to the die, the bullet is picked up by the sleeve and brought into alignment before it enters the die body or squashes your fingers. The seating stem (2) locates the nose of the bullet and the seater adjusting screw determines seating depth. Other manufacturers offer other approaches.

The RCBS Competition Die with side bullet loading and micrometer adjustment is a quality piece, RCBS offers a precision bushing and seating system, CH4D was a leader in offering Titanium Nitride (TiN) Coating in dies where carbide inserts were not an option. I get really good results with my handloads, so I don’t buy much of the specialized tooling. After trying just about all of the products out there I have settled on RCBS and Hornady dies for handgun and rifle ammo with custom cartridge die sets coming from CH4D.

Scales and Dispensers

“Well, that’s called a mechanical scale, son. People used them years ago before digital scales were available”. What can I say, I like my 10/10 scale, it is quick to use and doesn’t require an electrical outlet, or battery – still, I never use it anymore. Digital scales are relatively inexpensive, accurate and reliable. If you are fond of mechanical scales, a 500 grain capacity, magnetically dampened unit can be had for about $50 from any of the major equipment companies.

A good digital scale can be purchased in the range of $99~$150. I think the PACT BBK 2 Electronic Scale is a great value; capacity, accuracy, checking weights, and power source. Most of the majors make a similar product. I like AC power, although some like the PACT will run on a 9V or AA batteries. I worry about reading variations based on voltage drop off in use, and I am never that far away from an electrical outlet that battery power is required.

A good digital scale can be purchased in the range of $99~$150. I think the PACT BBK 2 Electronic Scale is a great value; capacity, accuracy, checking weights, and power source. Most of the majors make a similar product. I like AC power, although some like the PACT will run on a 9V or AA batteries. I worry about reading variations based on voltage drop off in use, and I am never that far away from an electrical outlet that battery power is required.

It is my humble opinion that data port scales designed to control power powder dispensers are a huge waste of time and money. The concept of powered charge metering is terrific, but the delays necessary to check and verify metering make for a too slow process. The latest RCBS unit, the RCBS ChargeMaster 1500 Powder Scale and Dispenser Combo is spec’d to meter 22 grains of powder in 16 seconds. Sounds fast ? Stare at a clock for 16 seconds, and think small powder charge; a full length magnum in one full minute. I have the prior generation set up and it is useless as a production tool, and too specialized in charge set up and calibration to make it a good load development tool.

Within the capability of these types of powder dispensers, one is as good an another, and that includes the very pricy Harrell models. Some are tuned for large cases, 50 grains or so and up, and some in the opposite direction. Manufacturers dress them up with brass hardware and micrometer adjustment to create the presence of precision, but functionally there isn’t a lick of difference. Pay $40 or $250 they work best with ball powder, struggle with multiple grain accuracy over a string of charges of extruded or stick powder and work best when used in a narrow configuration for a narrow application. I use a scale to meter charges mostly, however, on a good day with sub maximum charges I may load a pile of handgun ammo using this type of dispenser.

Powder tricklers are indispensable. Every equipment manufacturer makes one, they go for about $10, and are essential for quick adjustments to scale charges. I know there are battery powered models for twice the price, but this sort of defeats the purpose of the manually adding a tenth or two of powder at a time to top off a charge. I would only suggest that you select one that is made of cast metal rather than plastic, just for the sake of durability. You may want to get one from your primary equipment supplier so all of the colors will match on that decorator handloading bench…you big wus.

Priming Tools

I‘ve been using the RCBS APS priming system for years. I have tried other systems, press and bench mounted, and I’ve found nothing that compares. Press loaded systems jam at the worst times and primers get contaminated from powder debris and loading and unloading into tubes. More of a problem, because of the mechanical advantage of a handloading press, I can’t “feel” primers being properly seated and I have to rely on an mechanical stop adjustment and my consistent press actuation for proper assembly. I have settled on a bench mounted APS press which is very fast and reliable.

RCBS makes a hand held version for people who like to squeeze fit primers and a press mounted unit for anyone who wants to load from a progressive handloading press like the Pro 2000. The problem is the hand primer is only as consistent as a user’s handshake and the press mounted unit brings all of the problems inherit in press mounted priming systems. If you want to conserve funds and get by with a standard system, use the one that comes with the reloading press and exercise care in handling and set up. It is annoying to have a hammer drop and no bang to follow. Off press priming tools, APS or other wise run approximately $30 for handheld and $60 for bench mounted presses.

Measuring Equipment

Case length control is critical, particularly if the intention is to crimp. Cases longer than the set up length will over crimp and possibly bulge a case to the point it won’t chamber, short cases will under crimp and not sufficiently secure a bullet. Trimming to a uniform length will be a good step toward uniform crimping and all that is needed is a decent digital or plain caliper. This is a area that can get really expensive, quickly, but not necessarily. A decent digital caliper can be purchased at an auto parts store for under $15 with .001″ accuracy and resolution – more than enough for quality handloading and well within the control limitations of trimming and bullet seating equipment. A caliper of this type will also serve when used with bullet comparator or headspace tools.

Not a necessary piece of equipment, but case head measurement where .0002″ increases in a fired case means excess chamber pressure requires a more specialized tool; a 1″ range multi anvil micrometer for instance. You can save yourself a ton by purchasing a mechanical version with thimble readings from Enco for under $80 and .0001″ accuracy with a checking standard. A general machinist supply house will almost always be less costly than specialized versions of products sold through handloading equipment suppliers, and the selection will be more limited.

Lyman makes a simple profile gauge for checking case length. If all you need to do is check length from a selection of popular cartridges, $14 and you’re all set. For a buck more you can get a dial caliper, a much more flexible and accurate tool. Cartridge overall length is critical and a simple profile gauge designed to measure from bullet tip to primer face will not suffice, nor will taking measurement with a dial caliper referencing the same locations on a cartridge. Measurements need to be taken from the point on the bullet that would first contact the gun’s rifling to the rear of the cartridge, which requires a modestly priced specialized tool. Investing under $35 into a Stoney Point headspace gauge and another into a Stoney Point bullet comparator greatly improved the safety and quality of my handloads and optimized ammo for use with my firearms. These tools are easy to use and work with a wide range of cartridges. If you have a spare moment, you may want to check out the original detailed coverage of these items. Combined, these tools can determine each gun’s maximum cartridge length capacity, and measure assembled ammo to that specification.

Lyman makes a simple profile gauge for checking case length. If all you need to do is check length from a selection of popular cartridges, $14 and you’re all set. For a buck more you can get a dial caliper, a much more flexible and accurate tool. Cartridge overall length is critical and a simple profile gauge designed to measure from bullet tip to primer face will not suffice, nor will taking measurement with a dial caliper referencing the same locations on a cartridge. Measurements need to be taken from the point on the bullet that would first contact the gun’s rifling to the rear of the cartridge, which requires a modestly priced specialized tool. Investing under $35 into a Stoney Point headspace gauge and another into a Stoney Point bullet comparator greatly improved the safety and quality of my handloads and optimized ammo for use with my firearms. These tools are easy to use and work with a wide range of cartridges. If you have a spare moment, you may want to check out the original detailed coverage of these items. Combined, these tools can determine each gun’s maximum cartridge length capacity, and measure assembled ammo to that specification.

Lathe Type Case Trimmers

If you are loading bottle neck cases, a trimmer is a necessity, I have some 45 ACP and 40 S&W brass that hasn’t changed in length since…well, forever. I started with a manual RCBS unit, then went to a powered version when I noticed I would have to take a nap halfway through a 100 case session. I have a neat neck turning accessory that can only be used in manual mode, but it is pretty quick to use. The RCBS unit does not share shell holders with the RCBS presses, so these are an additional investment. The manual set up runs about $65, pilots and holders extra. The power unit can be added to a manual trimmer for about $165 or purchased as a set for only $179; cheaper than buying separately.

If you are loading bottle neck cases, a trimmer is a necessity, I have some 45 ACP and 40 S&W brass that hasn’t changed in length since…well, forever. I started with a manual RCBS unit, then went to a powered version when I noticed I would have to take a nap halfway through a 100 case session. I have a neat neck turning accessory that can only be used in manual mode, but it is pretty quick to use. The RCBS unit does not share shell holders with the RCBS presses, so these are an additional investment. The manual set up runs about $65, pilots and holders extra. The power unit can be added to a manual trimmer for about $165 or purchased as a set for only $179; cheaper than buying separately.

I think the Hornady manual trimmer is perhaps better made and offers more adjustment range for case length and better case lock up, but it does not really have a power drive unit. For $60 it is a solid piece of equipment. It uses Hornady press shell holders, pilots and .172″ cutter are extra cost accessories. Trimmers from Redding and Lyman are very similar to the RCBS unit in structure and price, Lyman also has a power drive unit, also similar in price.

Recently, I have been working with a Forster trimmer; there were two specific features that caused me to do so. The Forster unit performs the same functions as the other lathe type units, but it also was offered with optional bases to accommodate extremely short and long cases. In addition, Forster offers inside neck reamers, something I needed to thin brass on a specific wildcat cartridge case I formed from much larger diameter brass, without outside neck turning. A $10 adapter allows the use of an electric drill or screw driver for power and they offer a vertical power trimmer for approximately $49. Collets, sold separately for $8, retain cases while in operation. Regardless the specific selection, a trimmer is not a luxury item for bottle neck cartridges, it is a necessity for making good ammo. Manual is fine, power is a nice addition for volume, Forster offer some interesting functions not found in other brands.

Recently, I have been working with a Forster trimmer; there were two specific features that caused me to do so. The Forster unit performs the same functions as the other lathe type units, but it also was offered with optional bases to accommodate extremely short and long cases. In addition, Forster offers inside neck reamers, something I needed to thin brass on a specific wildcat cartridge case I formed from much larger diameter brass, without outside neck turning. A $10 adapter allows the use of an electric drill or screw driver for power and they offer a vertical power trimmer for approximately $49. Collets, sold separately for $8, retain cases while in operation. Regardless the specific selection, a trimmer is not a luxury item for bottle neck cartridges, it is a necessity for making good ammo. Manual is fine, power is a nice addition for volume, Forster offer some interesting functions not found in other brands.

Bullet & Stuck Case Pullers

Occasionally, just occasionally, something isn’t quite right and ammo needs to be disassembled, or perhaps a batch of ammo loses its identity. There are basically two types of tools that can pull a bullet without causing damage; inertial and collet. Inertial pullers, like the one pictured left from RCBS, are simple and adaptive. The only problem is pulling more than a few bullets can take a lot of whacking and these don’t hold up to heavy use.

Occasionally, just occasionally, something isn’t quite right and ammo needs to be disassembled, or perhaps a batch of ammo loses its identity. There are basically two types of tools that can pull a bullet without causing damage; inertial and collet. Inertial pullers, like the one pictured left from RCBS, are simple and adaptive. The only problem is pulling more than a few bullets can take a lot of whacking and these don’t hold up to heavy use.

Collet pullers work from a die station in the loading press. A collet, one for each bullet diameter, fits inside of housing that fits into the standard 7/8″x14 thread hole in a handloading press. The collet opened, the cartridge is raised in the press until the bullet enters the collet, then the collect is tightened around the bullet until it has a tight grip. Finally, the cartridge is lowered in the press and the case is pulled away from the bullet. Little effort is required and bullets generally are not damaged. The RCBS unit has a small T bar at the top of the puller housing that tightens the collet. The Hornady unit has a camming lever for quick tightening and release. There is a prior Real Guns article that covers all types in detail, including operation and price.

If you ever get in a hurry and attempt to full length resize a big case in a dry die you may discover the need for a stuck case puller. A stuck case puller can really come in handy if you don’t feel like living through the embarrassment and delay associated with sending a die stuck case back to the manufacturer for removal. The puller runs about $10~$12 and is easy to use. Basically, it is a drill, tap and Allen head bolt. You drill through the primer pocket, as long as there isn’t a live primer, tap the hole, insert a collar that straddled the die opening, put the bolt through the collar, and screw the bolt into the threaded case as the case is extracted from the die with each turn on the bolt. Easier to use than explain; not routinely required. In fact, I haven’t had a stuck case in years.

Case Cleaning and Prep

Case cleaning in really important and cases should not be final inspected or worked until this step is accomplished. There are a few methods of cleaning case – Vibratory cleaners are very common, utilizing ground walnut shell or corn cob media to clean. There are polish additives to make for a brighter finish. For about $60 you can have a large capacity unit with a clear and screen sifting lid that will handle over 1000 38 Special cases at a time. Not sure why manufacturers still reference the 38 Special as it has been about 2 decades since anyone has seen one. Another $10~$12 will fill it up with cleaning media. Sometimes these are called tumblers; they are not, they really are vibratory cleaners and once you plug one in, you will appreciate the description.

Case cleaning in really important and cases should not be final inspected or worked until this step is accomplished. There are a few methods of cleaning case – Vibratory cleaners are very common, utilizing ground walnut shell or corn cob media to clean. There are polish additives to make for a brighter finish. For about $60 you can have a large capacity unit with a clear and screen sifting lid that will handle over 1000 38 Special cases at a time. Not sure why manufacturers still reference the 38 Special as it has been about 2 decades since anyone has seen one. Another $10~$12 will fill it up with cleaning media. Sometimes these are called tumblers; they are not, they really are vibratory cleaners and once you plug one in, you will appreciate the description.

This is a tumbler, if you’ve ever collected rocks and tried to make large coarse rocks into smaller smooth rocks it will look familiar. A tumbler has a powered base that rotates, in this case, a five sided drum filled with dry or wet cleaning media. The drum’s internal five flats keep the empty cases and the user in a state of agitation. I believe RCBS is the only company still providing this type of equipment, which is unfortunate as it is probably a more flexible piece of equipment than a vibratory cleaner.

Extra drums can be purchased and preloaded with different media, wet or dry, just as extra dry hoppers are sold for a number of vibratory cleaners. At approximately $260 for the unit and $80 for extra drums, these are not inexpensive and they are probably borderline obsolete for the average handloader. The draw back for this type of equipment is small capacity; about 300 38 Special cases.

The easiest way to clean cases inside and out and have a bright finish is with liquid cleaner, a method I have switched to for almost all case cleaning. Birchwood Casey brass cleaner is sometimes difficult to find in stores or online, but it is really good stuff and comparatively inexpensive. It is also fast; 20 minutes and no noise. A $9 bottle will clean about 8,000 cases. Perhaps a bit easier to use, longer lasting as a solution, and made for larger quantities of brass is Iosso, which has been reviewed elsewhere on the site in great detail

The easiest way to clean cases inside and out and have a bright finish is with liquid cleaner, a method I have switched to for almost all case cleaning. Birchwood Casey brass cleaner is sometimes difficult to find in stores or online, but it is really good stuff and comparatively inexpensive. It is also fast; 20 minutes and no noise. A $9 bottle will clean about 8,000 cases. Perhaps a bit easier to use, longer lasting as a solution, and made for larger quantities of brass is Iosso, which has been reviewed elsewhere on the site in great detail

Iosso, at $15 per quart with soaking bucket and parts bag, will clean approximately 2,000 case – fast. In most cases 20 seconds is enough, in stubborn cases, a few minutes. A quart refill without the accessories is $8 or $25 for a gallon. Iosso cleaner removes powder fouling residue, oxidation, tarnish, discoloration, dirt, and grime. It also does a great job of cleaning inside of the casings and the primer pocket where tumbling media doesn’t do a very good job. If I were to do it all over again, I would probably use liquid cleaner exclusively. The only real precaution is don’t over soak, it will eat up the brass, and extra case must be taken to insure cases are dry inside before charging with power or seating a primer.

Other Stuff

Other small tools are necessary besides those supplied or required by the noted accessories, and they are every bit as important as a press when assembly quality handloads. A $10 deburring tool is necessary to clean up case mouths and allow a bullet to enter a case correctly. A primer pocket brush, bit reamer, will clean up gunk that could cause seating problems and contamination misfires. Personally, I think everyone should be issued a $5 J. Dewey Crocogator Universal Primer Pocket Cleaner as, unlike primer pocket brushes, it will last for a very long, long…long time. Loading blocks, loading trays and covered ammo boxes are essential. They seem to run about $5 no matter what they are or what size. In process handloads need to be identified and organized, finished ammo needs to be protected in storage and in use.

Other small tools are necessary besides those supplied or required by the noted accessories, and they are every bit as important as a press when assembly quality handloads. A $10 deburring tool is necessary to clean up case mouths and allow a bullet to enter a case correctly. A primer pocket brush, bit reamer, will clean up gunk that could cause seating problems and contamination misfires. Personally, I think everyone should be issued a $5 J. Dewey Crocogator Universal Primer Pocket Cleaner as, unlike primer pocket brushes, it will last for a very long, long…long time. Loading blocks, loading trays and covered ammo boxes are essential. They seem to run about $5 no matter what they are or what size. In process handloads need to be identified and organized, finished ammo needs to be protected in storage and in use.

There are lots of other specialty tools that can be purchased. I know I have them and I always know where they are because I virtually never use them. Cartridge headspace gauges, concentricity dial indicators, optical comparators, eye loops and other forms of magnifiers. Best bet is to visit Sinclair where you will find every piece of equipment made for the critical competitive shooter – great stuff, just doesn’t apply much for me. My determination of when I am making good or bad ammo is range and chronograph data. My handload objective is to shoot sub MOA, not sub half MOA. As long as I can meet that objective, anything more is an overkill. That said, this is probably the area where most handloaders differentiate themselves from others; the tools and tricks of the trade, so to speak, that they feel will give them an edge toward meeting their personal objective.

I hope there was some useful information here. I thought my stumbling and bumbling and coming to realizations might spare you some time and money, or maybe even give you an idea where to spend more of both.

Joe

Email Notification