If the number of bullet types and manufacturers active in the market is a sign of firearms industry health, we’ve got to be in pretty good shape. It’s nice to see the effort being made by manufacturers in experimentation and research and development. I was sifting through piles of boxes on my bench, thinking it may be time to standardize on a few and eliminate the rest, when I decided I needed to make one more round of personal research to try some of the newer and more specialized products before reaching a conclusion.

If the number of bullet types and manufacturers active in the market is a sign of firearms industry health, we’ve got to be in pretty good shape. It’s nice to see the effort being made by manufacturers in experimentation and research and development. I was sifting through piles of boxes on my bench, thinking it may be time to standardize on a few and eliminate the rest, when I decided I needed to make one more round of personal research to try some of the newer and more specialized products before reaching a conclusion.

The arrival of a package from Midway USA was different than most bullet deliveries for a couple of reasons. First, almost a year ago, I had stopped buying from Midway USA; too many out of stock items, the delivery of a used or blemished scope as new material, incorrect order status. I made a decision to try Midway again, with the hope the original problems I experienced with them were only temporary in nature. Second, the invoice for 3 boxes of 50 bullets each was $135 and change, compared to about $35 for my more typical selection. The cost of working up bullet selection can carry some pretty steep price tags.

My Midway order shipped the day it was received, the material arrived within 4 business days, and every thing was as ordered – even the typically hard to locate items. So I’ll keep buying, unless some event causes me to assume my original opinion. The steep invoice for bullets wasn’t a Midway issue. In fact, the price was pretty competitive for any mail order supplier, and untouchable through local retail. The fact that Midway carries an extensive selection of these types of bullets goes into their “plus column”. The trend in bullets is for special purpose, or special situation products at two and three times the cost of general purpose goods.

Determining a basis for evaluation

I don’t think the features described on a box of bullets, or on a product data sheet matter very much. They are, after all, the benefits expressed by the company that is trying to sell them, and perhaps not exactly reflecting how the product would be generally used. So I started making a personal priority list of the elements would be important to me in bullet selection, based on my use of the product and my type of shooting.

Cost: Primarily, I handload to reduce cost of ammo. I can build a box of .338-378’s for under $17 with excellent components, rather that buy a box of 20 over the counter for $85. With these savings, I can generate more ammo and still have enough money left over to buy a bore scope. Then, I can use the bore scope so I can tell when I’ve shot out the Weatherby barrel from all of this extra ammo. On the average, specialty brand/type bullets would add $14 to that $17 box of handloads. Not insignificant, and cause to expect some practical benefit from these types of bullets.

Cost: Primarily, I handload to reduce cost of ammo. I can build a box of .338-378’s for under $17 with excellent components, rather that buy a box of 20 over the counter for $85. With these savings, I can generate more ammo and still have enough money left over to buy a bore scope. Then, I can use the bore scope so I can tell when I’ve shot out the Weatherby barrel from all of this extra ammo. On the average, specialty brand/type bullets would add $14 to that $17 box of handloads. Not insignificant, and cause to expect some practical benefit from these types of bullets.

Manufacturing Uniformity: Bullets made the same, shoot the same, an attribute in a bullet that could make hand loaders look a lot better as shooters. Consistent weight, concentricity and security of jacket and core, balance, could all add up to tighter groups, a more predictable point of impact and improved field accuracy. In everyday product, there can be significant variation from one brand to another, or even within the same box of bullets. Comparative uniformity could be a key indicator of real quality, not just a price tag issue.

Flexibility and Availability: Handloading permits me to try many cartridge combinations mass producing factories wouldn’t touch. An array of specialized bullets could extend this horizon for me, hopefully extending my list of practical loads. In addition, sporting goods stores don’t always stock a great variety of the types of cartridges I like to shoot, in fact some stores don’t even stock things I don’t like to shoot. I picked up my .338-378 about 15 minutes after a version chambered for this cartridge hit the stores. 10 minutes after that, I discovered I could buy any factory load I wanted, as long as the selection used 200 grain bullets. By the next day, armed with 40 recently emptied cases and a sore shoulder, I was able to load a decent spectrum of bullet weights and loads for my new gun. Bullets I would select for ongoing use needed to be routinely available.

Extreme Accuracy Potential: Not a leading reason for me to handload. I’ve never really found a gun that wouldn’t eventually respond to some factory load, and consistently produce exceptional accuracy results, and most of my handloading effort goes into getting that same level of accuracy across a greater number of combinations. I can get consistent sub MOA out of cost effective (cheap) Sierra 250 and 200 grain Spitzer soft points. I’m sure there are bullets like the 300 grain match product from Sierra that would really drop them in at 500 yards, but not with my finger on the trigger.

Reliable Hunting Performance: A lot seems to be said about jacket toughness, core bonding, controlled expansion and weight retention in premium bullets. Outside of hunting situations the issue would be irrelevant, and in hunting situations I’m not sure there has been a problem to solve for quite some time. For the past 20 years or so this may be an area of diminishing returns for bullet manufacturers and hunters. I can’t remember pulling a fragmented bullet out of an animal that was shot even at very close range. I’ve never had a bullet that didn’t properly expand, unless I was shooting at something too far away, with a bullet that was traveling too slow and way, way out of it’s design parameters when it hit. I’ve never had a bullet shed a jacket. I’m sure it happens, but just not within my realm of experience.

Some people hunt all of the time, for all sorts of game, under all types of conditions. Periodically, I am a seasonal, regional North American Hunter. On top of that, my hunting stories are incredibly boring, “I took the shot and it feel over”, followed by the astute observation, “I found the bullet mushroomed at the end of the wound channel”, or “I could see the entire state of Kansas through that exit wound”. Key here is that the animal is always available for a postmortem. If I were hunting something big, something very tough and close up, I wouldn’t be using handloads. I don’t think I have the knowledge to compensate in handloads, and take into consideration the effects of extreme temperature and humidity in another country, on another continent. I just wouldn’t want to hear the “pffsst” of a squib load depositing a bullet half way down the barrel, as several thousand pounds of meat with horns is closing at 20 feet.

With these elements to consider, I made a pile of all this gunk and started weeding my way through it.

How do they compare ?

|

Brand | Type | Grains | Qty | Price | Unit cost |

| Sierra | Game King Spitzer BT |

250 | 50 | 13.99 | .28 | |

| Nosler | Ballistic Tip Spizer BT |

200 | 50 | 13.99 | .28 | |

| Speer | Boat Tail Spitzer BT |

225 | 50 | 16.99 | .34 | |

| Speer | Grand Slam Semi Spitzer |

250 | 50 | 25.99 | .52 | |

| Barnes | XLC Spitzer |

225 | 50 | 38.99 | .78 | |

| Swift | A-Frame Semi Spitzer |

275 | 50 | 47.99 | .96 | |

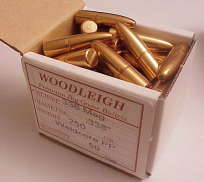

| Woodleigh | Weldcore PP Semi Spitzer |

250 | 50 | 48.99 | .98 | |

|

L to R: Sierra 250 gr, Speer 225 gr, Speer 250 gr, Nosler 200 gr, Barnes 225, Swift 275, Woodleigh 250 |

||||||

Price: Sierra is the consistent price leader and about the same in both 200 grain and 250 grain versions of the Game King. Nosler, typically a premium brand, comes close with its Ballistic Tip but they only offer heavier weights in their “Partition” line at over 3 times the cost. Grand Slams have already increased my $17 box of ammo by $5 and Woodleigh increases cost by $14.

Table Legend – Table Legend –

The table indicates measurement taken from 5 random samples pulled from each box of 50. The last column entry of the extreme spread within that population. L = overall length of bullet |

Sierra 250 |

L | 1.442 | 1.439 | 1.442 | 1.442 | 1.442 | .003 |

| D | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .000 | ||

| OR | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | ||

| W | 250.0 | 249.8 | 250.0 | 249.9 | 249.9 | .2 | ||

| Speer 225 |

L | 1.293 | 1.288 | 1.288 | 1.289 | 1.293 | .004 | |

| D | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .000 | ||

| OR | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | ||

| W | 225.2 | 225.2 | 225.4 | 225.4 | 225.3 | .2 | ||

| Speer 250 | L | 1.333 | 1.331 | 1.329 | 1.332 | 1.334 | .005 | |

| D | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .000 | ||

| OR | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | ||

| W | 249.9 | 250.0 | 249.5 | 249.5 | 250.1 | .6 | ||

| Nosler 200 | L | 1.334 | 1.335 | 1.335 | 1.334 | 1.334 | .001 | |

| D | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .000 | ||

| OR | .0005 | .0005 | .0005 | .0005 | .0005 | .0005 | ||

| W | 200.3 | 199.8 | 200.2 | 201.0 | 200.0 | .5 | ||

| Barnes 225 | L | 1.384 | 1.383 | 1.384 | 1.384 | 1.384 | .001 | |

| D | .340 | .339 | .339 | .339 | .340 | .001 | ||

| OR | .0005 | .0000 | .0000 | .0005 | .0000 | .0005 | ||

| W | 225.5 | 225.2 | 225.2 | 225.5 | 225.2 | .3 | ||

| Swift 275 | L | 1.443 | 1.441 | 1.440 | 1.438 | 1.440 | .005 | |

| D | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .000 | ||

| OR | .0005 | .0005 | .0005 | .0005 | .0005 | .0005 | ||

| W | 274.5 | 274.4 | 274.5 | 275.0 | 275.6 | 1.2 | ||

| Woodleigh 250 |

L | 1.292 | 1.293 | 1.290 | 1.290 | 1.293 | .003 | |

| D | .338 | .338 | .338 | .338 | .337 | .001 | ||

| OR | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | ||

| W | 250.0 | 250.5 | 250.1 | 249.2 | 250.2 | 1.3 |

Manufacturing Uniformity: Both Sierra and Speer seemed to have a handle on uniform production, virtually tied for bullet to bullet consistency. Significant variation in length could impact bullet seating and distance to rifling measurements, under/oversized diameters could have an impact on velocity potential, and inconsistent weight could vary MV and accuracy. I’d assume an out of round condition presents the most significant potential accuracy and trajectory problems as a bullet begins to move down range and attempts to stabilize around the actual bullets axis and CG. However, this would probably only be at issue if the out of round condition were the result of a lack of uniform thickness in the bullet’s jacket, which may cause an out of balance condition to persist after the bullet leaves the barrel. If the jacket thickness is uniform, the combination of a straight bore, a lot of heat and pressure make for an excellent swaging tool, and what comes out should be without the .005″ out of round condition.

I don’t believe the Barnes bullets had the same problem as the Swift and Nosler products. The Swift and Nosler out of round condition was very consistent from one bullet to the next, reflective of process results and acceptable manufacturing tolerance. The Barnes bullets OR was not always present from one bullet to the next, and appears to be more related to Barnes not maintaining uniform application of their proprietary coating. Not knowing the weight of the coating, or condition of the coating when the bullet exits the barrel, I couldn’t forecast the impact on bullet performance if, in fact, there was any.

Variations in weight, within these recorded ranges, are a non-event when it comes to practical ballistic considerations. In the case of the Woodleigh, an extreme spread of 1.3 grains in bullet weight, assuming a baseline of 3200 fps and a bullet weight of 250 grains, would yield essentially: no measurable difference in bullet trajectory, approximately 20 ft/lbs in kinetic energy, and 4 to 5 fps in velocity.

Flexibility and Availability:

Sierra Game King: Available through many Internet and local retail outlets. After taking out the shipping cost component, the prices on the Internet are very much the same, but at least 30% less expensive than retail in this area, not even taking into consideration sales tax.

Sierra Game King: Available through many Internet and local retail outlets. After taking out the shipping cost component, the prices on the Internet are very much the same, but at least 30% less expensive than retail in this area, not even taking into consideration sales tax.

Sierra does sell specialized bullets on a direct to customer basis, but not the Game King line. They can be purchased in 215 and 250 grain versions, the two most popular hunting weights for the .338 bore in magnum capacity cartridges.

Nosler Ballistic Tip: The Ballistic Tip is only available in the lighter 180 and 200 grain versions. The heavier bullets are reserved for Nosler’s pricey Partition line. Nosler does not sell direct to customers, all products are readily available on the Internet, but tend to require a day or two to arrive from local distribution when purchased from a retail dealer.

Nosler Ballistic Tip: The Ballistic Tip is only available in the lighter 180 and 200 grain versions. The heavier bullets are reserved for Nosler’s pricey Partition line. Nosler does not sell direct to customers, all products are readily available on the Internet, but tend to require a day or two to arrive from local distribution when purchased from a retail dealer.

The 200 grain is able to reach a .250 sectional density, about the threshold for proper bullet weight for sustainable energy and flat trajectory for most bore sizes.

Speer Boat Tail and Grand Slam: The Boat Tail in 225 grain version only and is readily available. Speer makes an even less expensive 200 grain. No problem with having access to them, I just overlooked them. Speer does not sell any bullet products direct to customer.

Speer Boat Tail and Grand Slam: The Boat Tail in 225 grain version only and is readily available. Speer makes an even less expensive 200 grain. No problem with having access to them, I just overlooked them. Speer does not sell any bullet products direct to customer.

Speer pushes the 250 grain bullet into the Grand Slam line and eliminates this very popular weight from their low cost bullet offerings. Grand Slam bullets were easy to locate on the Internet, not so at local retail stores.

Barnes: The XLC, coated solid copper X bullets, are available in 185 grain and 225 grain version. The uncoated X line bullets are available in the range of 160 – 250 grains. I could only locate 225 grain XLC’s in local stock, but most of the X series above 185 grains were available. I could find virtually all types of Barnes bullets in just about all weights in stock with online operations.

Barnes: The XLC, coated solid copper X bullets, are available in 185 grain and 225 grain version. The uncoated X line bullets are available in the range of 160 – 250 grains. I could only locate 225 grain XLC’s in local stock, but most of the X series above 185 grains were available. I could find virtually all types of Barnes bullets in just about all weights in stock with online operations.

Barnes does not sell customer direct, however, they do seem to have an impressive list of dealers and distributors. Barnes is the only manufacturer to squeeze some supplementary load data into their bullet boxes. A nice touch, especially for .338-378 owners.

Swift: Their A Frame product is available in three very nice weight selections for the .338 bore; 225, 250 and 275 grains. I could not locate them in local retail outlets, nor in many online operations. I did find them at Midway USA, and they were in stock for immediate shipment. Price is the same across the weight range. Swift, like the Speer Grand Slam comes packaged with individual spots for each bullet so they are protected in shipment. I spend half an hour trying to fish one out before I dumped the box out on the counter.

Swift: Their A Frame product is available in three very nice weight selections for the .338 bore; 225, 250 and 275 grains. I could not locate them in local retail outlets, nor in many online operations. I did find them at Midway USA, and they were in stock for immediate shipment. Price is the same across the weight range. Swift, like the Speer Grand Slam comes packaged with individual spots for each bullet so they are protected in shipment. I spend half an hour trying to fish one out before I dumped the box out on the counter.

Swift has owned the swiftbullets.com domain since July 99, and it’s listed on Shooter’s name servers, but I was unable to locate a functional Swift bullet web site for further information.

Woodleigh: I have the feeling there is a little P.T. Barnum at work here. With bullet weights available in the .338 bore from 225 to 300 grains and in every type of tip from solids to protected point, wherever found the caution, ” Hard to import from Australia, may or may not be available, willing to backorder for you…..” Where they were listed as being sold on the Internet, they were available for immediate shipment. Local retailers thought I was being humorous when I asked if they carried Woodleigh.

Woodleigh: I have the feeling there is a little P.T. Barnum at work here. With bullet weights available in the .338 bore from 225 to 300 grains and in every type of tip from solids to protected point, wherever found the caution, ” Hard to import from Australia, may or may not be available, willing to backorder for you…..” Where they were listed as being sold on the Internet, they were available for immediate shipment. Local retailers thought I was being humorous when I asked if they carried Woodleigh.

Selling as a tough jacketed bullet for rugged game, they are also sold in conjunction with Premium ammo from Federal and others.

General Observations

I’m going to take a break here and finish up the examination and shooting portions for the next and final installment. I pretty much know what to expect from some of the bullets from previous experience, so I will be able to baseline and make sure the gun is capable of shooting as well as it was the last time I published data.

The Swift looks a lot like the Grand Slam with an almost identical ogive profile, but a distinctly with a longer shank to get to the 275 grain weight. It’s nice to see the weight wasn’t pushed to the front where it would blunt the nose and decrease the ballistic coefficient, but that shank is .680″ long compared to a more typical .450″. The result is case capacity drops 20 grains to accommodate the material below the cannelure vs. 15 grains for the shorter bullet shank.

The Swift looks a lot like the Grand Slam with an almost identical ogive profile, but a distinctly with a longer shank to get to the 275 grain weight. It’s nice to see the weight wasn’t pushed to the front where it would blunt the nose and decrease the ballistic coefficient, but that shank is .680″ long compared to a more typical .450″. The result is case capacity drops 20 grains to accommodate the material below the cannelure vs. 15 grains for the shorter bullet shank.

In a cartridge like the .338-378 the result is mild charge compression perhaps with IMR 7828, maybe a little more with RL 25. But in a smaller case like the .338 Winchester, the extra length may prevent max loads as a result of the lost capacity. Water capacity drops from 71.5 to only 66.2 grains. The only other odd construction used in the Swift bullet was the open base, a lot like a tube jacket.

I’m doing more research on the Woodleigh bullet so I can fill in more of the blanks in the blanks in the next installment. In the picture adjacent to the previous paragraph you may be able to see how much thicker the ogive is on the Woodleigh than the Swift or the Speer. At this point I assume the ballistic coefficient for the Woodleigh isn’t all that good.

I’m doing more research on the Woodleigh bullet so I can fill in more of the blanks in the blanks in the next installment. In the picture adjacent to the previous paragraph you may be able to see how much thicker the ogive is on the Woodleigh than the Swift or the Speer. At this point I assume the ballistic coefficient for the Woodleigh isn’t all that good.

Of the six bullets in this picture, one was received with a badly damaged tip and another is a “pull”. There is a distinct case ring around the bullet shank and some surface corrosion. I’m not sure what that’s all about or how it would have gotten mixed into a box of new bullets.

The jacket material is a different color than most, which seems to be the result of a unique mix of materials used in the jacket construction. I’ll be back in a couple of weeks with the final results from the range and description of any problems that might have been encountered on the way to develop new loads.

More “The .338-378 Weatherby Revisited”:

The .338-378 Weatherby Revisited Part I

The .338-378 Weatherby Revisited Part II

Handload Data 338-378 Weatherby Magnum

Thanks,

Joe

Email Notification