Okay, I’m one of those guys who pokes at the firearms industry for a perceived lack of technological development, and the absence of magnetic pulse propulsion. Meanwhile, I can’t even easily make the short leap from mechanical to electronic scale. This story represents my journey from the dark world of mechanical gadgetry, to world of electronic enlightenment.

Okay, I’m one of those guys who pokes at the firearms industry for a perceived lack of technological development, and the absence of magnetic pulse propulsion. Meanwhile, I can’t even easily make the short leap from mechanical to electronic scale. This story represents my journey from the dark world of mechanical gadgetry, to world of electronic enlightenment.

Powder measurement and dispensing is to handloading, what the keyboard is to computing; the slowest, most human skill dependent, least reliable step in a functional process. Give me a cartridge that holds between 5 and 50 grains of ball powder, a progressive press with an automated powder level checker stuck in one die head location, and I’ll intrepidly crank away making thousands of rounds of ammo, with an on-press dispenser throwing the charges. Move me away from production, into short runs with large capacity cases, things begin to change – when 7mm mag and .257 Weatherby rounds start zipping around on the shell plate, I’m ready for an off-press dispenser that will allow me to closely control the powder charging process.

At the 110 grain plus case capacity level, I’m ready to start counting physical grains of powder, or at least weigh every single charge. It’s either those choices or run the risk of being the first to place an Ultralight Weatherby into low orbit as a result of an incorrect powder charge. I have tried numerous gravity feed, cavity metered systems, and none have been capable of throwing uniform large charges of long grained powder such as IMR 7828, or even shorter RL 25 shown at the right. Most even have a problem with large doses of finer grained powders, such as H870 or H1000.

At the 110 grain plus case capacity level, I’m ready to start counting physical grains of powder, or at least weigh every single charge. It’s either those choices or run the risk of being the first to place an Ultralight Weatherby into low orbit as a result of an incorrect powder charge. I have tried numerous gravity feed, cavity metered systems, and none have been capable of throwing uniform large charges of long grained powder such as IMR 7828, or even shorter RL 25 shown at the right. Most even have a problem with large doses of finer grained powders, such as H870 or H1000.

I believe the much of the problem with large charge metering is caused by a lack of uniform powder density within the dispenser’s hopper. Use up a third of the hopper volume, letting the operating handle bump the dispenser a number of times, and charges will become uniform. Unfortunately, as the hopper is at it’s last third of capacity, the weight filling the cavity is less and the charges start to throw lighter. In any event, I though it was time to find a better way, or weigh….Sorry.

I don’t know many companies actually manufacture popular electronic scales, however, I’m sure it’s far fewer than there are brand names. As cleverly disguised as they are with different logos, and plastic colors, many share an almost identical appearance. If you’ve seen the RCBS Powder Pro Digital Scale and Powder Master Electronic Dispenser along side of PACT’s Digital Precision Powder Scale and Digital Precision Powder Dispenser, you probably understand what how similar these products can be.

While weeding my way through the different products, I concluded there are cheap scales and expensive electronic scales, however, there are no inaccurate scales. I believe virtually everything on the market guarantees tenth grain accuracy within their lower powder measuring weight ranges, just like their mechanical counterparts. The smallest of these scales usually have a low and high operating range of approximately 0-350 grains and 350-750 grains respectively. Accuracy may diminish to two tenths of a grain in the upper operating range, primarily because reading error is actually expressed as a percentage rather than in absolute weight. What about people who handload at the edge, and find less than one tenth of a grain to be critical to their maximum loads ? Well, considering a mouse fart could raise ambient temperature enough to negate a tenth grain over/under difference, there is a special requirement here that may be beyond the scope of this article.

The big price differential between a cheap and expensive electronic scale is based only on a few factors: whether or not is being sold through Dillon, the scale’s maximum weight range – 750 grains for the cheapies and 1500 for the expensive, uniform one tenth accuracy across the scale’s entire weight range and, finally, the existence of a data port. The higher prices electronic scales typically have an infrared port that can transmit data to a printer or, as we’ll see later, to a special powder dispenser. The powder draw of the data port technology may be the reason non-port scales are found in AC/battery and battery power only configurations, while port models are only available in AC versions.

The PACT BBK is typical of the lower cost electronic scales. It is powered by a 9 volt battery and has a capacity of 750 grains / 50 Grams. The scale is accurate within a tenth of a grain, up to 300 grains, and within and +- two tenths from 300 to 750 grains. The BBK comes with two check weights for calibration.

The PACT BBK is typical of the lower cost electronic scales. It is powered by a 9 volt battery and has a capacity of 750 grains / 50 Grams. The scale is accurate within a tenth of a grain, up to 300 grains, and within and +- two tenths from 300 to 750 grains. The BBK comes with two check weights for calibration.

This type of scale has no greater accuracy than a quality mechanical scale. Just like their mechanical counterparts, they are sensitive to drafts, temperature changes and heavy handed treatment. The low cost versions are susceptible to drift and require periodic recalibration. The PACT is available for under $89. Its twin, the RCBS Partner is priced at $125.

Dillon’s D-Terminator electronic scale offers a slight improvement over the PACT BBK category, but none that would necessarily be helpful in routine applications. Like the BBK, the Dillon is also a standalone item and not made to integrate with printers or dispensers. The top weight handled is upped to 1200 grains and the scale works with either battery or AC power sources. The product looks a little dated in that Dillon is stating the scale has the highest capacity on the market, no longer the case, and they point to being the only product with an angled display for better viewing – essentially all of the electronic scales I looked at have the same type and size display. Accuracy is reported as one tenth grain over the weight range. Retail is $169.

Dillon’s D-Terminator electronic scale offers a slight improvement over the PACT BBK category, but none that would necessarily be helpful in routine applications. Like the BBK, the Dillon is also a standalone item and not made to integrate with printers or dispensers. The top weight handled is upped to 1200 grains and the scale works with either battery or AC power sources. The product looks a little dated in that Dillon is stating the scale has the highest capacity on the market, no longer the case, and they point to being the only product with an angled display for better viewing – essentially all of the electronic scales I looked at have the same type and size display. Accuracy is reported as one tenth grain over the weight range. Retail is $169.

My Choice

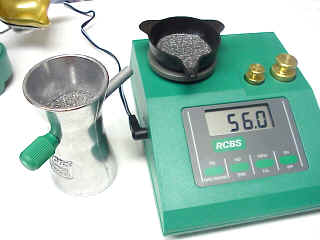

The RCBS Powder Pro Digital Scale, at 1500 grains, has the greatest capacity of the scales I evaluated, and best +/- tolerance over the entire range. The Powder Pro features an infrared data port which would help me toward my goal of improved metering and dispensing. The scale is powdered with an AC adapter, rather than battery, which is a preference for me – I really dislike dead batteries, and not since the old Miami Vice TV series have I seen a need for a portable powdered scale.

The RCBS Powder Pro Digital Scale, at 1500 grains, has the greatest capacity of the scales I evaluated, and best +/- tolerance over the entire range. The Powder Pro features an infrared data port which would help me toward my goal of improved metering and dispensing. The scale is powdered with an AC adapter, rather than battery, which is a preference for me – I really dislike dead batteries, and not since the old Miami Vice TV series have I seen a need for a portable powdered scale.

I purchased the RCBS product for $169 locally; it’s listed typically at $179 on the Internet. FYI, the PACT Digital Precision Powder Scale (same important specs, different color) is approximately $30 less.

Electronic versus Mechanical Scale

My original RCBS 10-10 has been a very reliable piece of equipment and able to meet all of my handloading needs.

My original RCBS 10-10 has been a very reliable piece of equipment and able to meet all of my handloading needs.

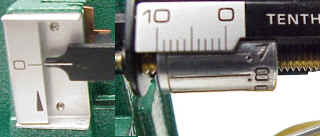

The scale can handle weights up to 1,010-grains +/- 0.1-grain A micrometer poise allows adjustment from 0.1 to 10 grains. The scale has magnetic dampening, self-aligning agate bearings, hardened steel pivot knives and a plastic cover.

There are many good things to say about a product of this type. There are no components that will drop dead at the worst possible moment, the scale is pretty sturdy and there is no battery to fail or an electrical outlet to find. Once a little skill is developed, weighing charges is actually pretty quick. The 10-10 runs about $100, with lesser capacity mechanical scales priced as low a $30.

I began with check weights on both scales. Check weights are accurate standards used to verify and calibrate both mechanical and electronic scales. I had on hand 10, 20 and 50 gram weights. The electronic scale has a high and low calibration mode, with the cross over point equal to 20 grams. 20 grams on the electronic scale weighed in at 308.7 grains, rather than the correct 308.6, which I felt might

I began with check weights on both scales. Check weights are accurate standards used to verify and calibrate both mechanical and electronic scales. I had on hand 10, 20 and 50 gram weights. The electronic scale has a high and low calibration mode, with the cross over point equal to 20 grams. 20 grams on the electronic scale weighed in at 308.7 grains, rather than the correct 308.6, which I felt might  be an issue of digital rounding, or and indication of the +/- tenth grain accuracy. Oddly enough, the mechanical scale, as can be seen on the beam and poise pictures, indicated the exact same weight as the electronic scale, 308.7. My conclusion was, if I could weigh in within less than one tenth of a grain on both, and I truly needed to look for some criticism of greater significance. Note: I eventually was able to verify the weight using more accurate lab equipment and found it to be off approximately .005 grains.

be an issue of digital rounding, or and indication of the +/- tenth grain accuracy. Oddly enough, the mechanical scale, as can be seen on the beam and poise pictures, indicated the exact same weight as the electronic scale, 308.7. My conclusion was, if I could weigh in within less than one tenth of a grain on both, and I truly needed to look for some criticism of greater significance. Note: I eventually was able to verify the weight using more accurate lab equipment and found it to be off approximately .005 grains.

The other check weights all came in correctly on both scales. The digital display numbers rolled a little if the surface the scale was sitting on was measurably bumped. But then again the beam on the mechanical scale bobbed when bounced, then eventually settled into a stable reading.

At this point things really got exciting. I weighed many different types of powders and compared readings for differences – there were none. Then I tried working with a trickler to see of the electronic scale was sensitive enough to pick up very small dribbles of powder; it was and it did.

At this point things really got exciting. I weighed many different types of powders and compared readings for differences – there were none. Then I tried working with a trickler to see of the electronic scale was sensitive enough to pick up very small dribbles of powder; it was and it did.

I tried timing myself measuring off 20, 100 grain units of powder on both scales in search of a speed benefit from one or the other; nothing. The digital display kept up with the electronic scale and the electronic scale kept up with me. I frequently preset scale weight, then trickle powder until the beam lines up on zero. With the digital scale I could trickle powder and watch the increments rack up until I reached the desired reading. Temperature in the room didn’t seem to vary enough to alter either scale’s reading, and a breeze from an active air conditioning vent caused the digital reading to wander a couple of tenths, and the mechanical scales beam to wander a similar amount. Both worked normally when taken out of the moving air stream.

Conclusion Part I

At this moment I cannot see any benefit to the digital scale over the mechanical scale. The mechanical scale has fewer parts, no springs or parts that will change over time and it weighs material in at the same level of accuracy and consistency as the more expensive digital product. For part II, I’m going to bring in the automated dispenser system, tie it in to the digital scale and see if the combination is worth more in delivered time and accuracy than the mechanical scale and the mechanical measure.

Thanks,

Joe

Email Notification