The 1895G is truly an interesting firearm, and perhaps one with a split personality.

The 1895G is truly an interesting firearm, and perhaps one with a split personality.

The dominant trait? Accuracy. I was a person who believed lever gun groups could only be measured in feet. I struggled with an old Marlin 336 .30/30 to keep most of the lead in a 6″ circle. Consequently, I could only use it to hunt incredibly large deer.

I don’t know what Marlin did to address this issue when they designed the 1895G, but the gun is as accurate as most of my bolt action rifles. It didn’t even seem to matter what bullets or loads I was shooting, group size was close, even though point of impact shifted significantly with each different handload. The only odd component of the accuracy issue, is the rifle’s metallic sights, which can’t bring shot placement within 5 inches of a vertical bullseye. Curiously enough the scope, after being mechanically and optically aligned to bore center, needed to be cranked up a huge amount to be on vertical target. My guess is there is some pressure on the barrel, or odd harmonic at work here, but I haven’t taken the time as yet to explore this issue.

The unpleasant side

I shot boxes of factory 300 grain .45-70 Remington factory loads that were incredibly accurate, mild in recoil and muzzle blast, without so much as having to blink. I really enjoyed that part of the day. Unfortunately, I began my handload evaluation with 400 and 405 grain full up loads, and recoil could only be described as fierce. To put the definition of “fierce” in context, I spend a great deal of time shooting high end loads for the .416 and .338-378 Weatherby Magnums without a muzzle brake, and they don’t bother me at all. The 1895G .45-70 hot loads are just plain nasty and I was left with a blood red shoulder bruise as a memento. Where does this smack attack come from?

A 300 grain bullet, chugging along at 1,700 fps kicks up about 25 ft/lbs of recoil from the Marlin. A 405 grain bullet clocking along at 2,000 fps results in a thumping 56 ft lbs of recoil. That is about the same as a 300 grain .375 H&H bullet leaving the muzzle at 2700 fps. The gun belched flames, pitched the muzzle up and out of the rest, and kicked very sharply. The process was environmentally objectionable enough for people on adjacent benches to move over by one or two spots. The gun is just not designed for this level of cartridge performance; not in reference to the strength of the rifle, but rather its geometry.

The gun is laid out like a fence post. It is light, made to come straight back at the shooter and has a recoil pad that’s as non-shock absorbing as a brick. Marlin should have tossed in the extra “buck-fifty” for a quality Sorbothane pad. The muzzle brake, while seemingly ineffective in reducing rearward thrust, did seem very good at scorching the eyebrows off of shooters immediately to the right and left of the muzzle. Yes, the Guide Gun has maintained it’s traditional saddle carbine heritage, but not without a penalty to the shooter. It is not made to shoot volumes of heavily charged ammo from a bench at paper targets. At 2,000 fps for a 400 grain bullet, and 3,500 ft/lbs of ME, there aren’t too many moose, black bear or elk that would duck this gun, at least well inside of 200 yards; actually, lets call it 150 yards.

Accuracy

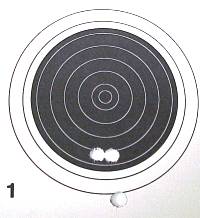

And here, of course, is the reason why none of my other whining about recoil is of consequence. That is a three shot .750″ group at the top left, and a group of even smaller dimensions, below and to the right. I could consistently shoot this way, regardless the bullets selected or charge, with the exception of Win 748 loads, which were compressed and would not group below 1.5″.

And here, of course, is the reason why none of my other whining about recoil is of consequence. That is a three shot .750″ group at the top left, and a group of even smaller dimensions, below and to the right. I could consistently shoot this way, regardless the bullets selected or charge, with the exception of Win 748 loads, which were compressed and would not group below 1.5″.

Of the four powders I used to assemble these loads, Winchester was the only ball powder. The rest were stick or cylindrical, and none within this group were compressed. I think I could have done considerably better than what appears here, but to tell you the truth, after 30 rounds or so the recoil was distracting.

There is another side to this issue that is my only point of concern. Bullets and charges altered point of impact significantly. The target on the right shows a 2 shot group of 400 grain Speer bullets, the one shot below was a 405 grain Remington bulk bullet.

There is another side to this issue that is my only point of concern. Bullets and charges altered point of impact significantly. The target on the right shows a 2 shot group of 400 grain Speer bullets, the one shot below was a 405 grain Remington bulk bullet.

Within a powder type group, but varied bullet weights, the 400 and 405 grain bullets would almost always shoot 3″ away from the 350 grain bullets, then another inch further to the 300 grain bullets, but that offset could be above, below, to the left, etc. I guess my word of advice is to sight in with a specific load, and bring enough ammo with you, so you won’t have to sight in again.

I would be remiss in not noting the Leupold Vari-X II 2-7x scope and solid one piece mount were very nice to work with, and both held adjustments even when exposed to a lot of bouncing around. The 7x is more than enough for this rifle and the low end presented an extremely wide field of view. Nicer still, there seemed to be a decent amount of eye relief latitude, so coming up with a good sight picture was quick and easy.

A couple of comments before the handload data

No brass was killed in the production of this article. No flat primers, no flow through bolt face cavities and no flattened headstamps. All that means is relatively conservative loading. I would doubt if a lever action of this type would yield much in the way of traditional high pressure symptoms, much in advance of something breaking. I noted in the last installment, Remington ammo burned dirty, but I thought this might be a function of this cartridge. No chance, the handloads (left) burned clean.

No brass was killed in the production of this article. No flat primers, no flow through bolt face cavities and no flattened headstamps. All that means is relatively conservative loading. I would doubt if a lever action of this type would yield much in the way of traditional high pressure symptoms, much in advance of something breaking. I noted in the last installment, Remington ammo burned dirty, but I thought this might be a function of this cartridge. No chance, the handloads (left) burned clean.

The Marlin’s trigger pull was of aerobic quality, 5 3/4 lbs. It was clean and there was no creep, but on several occasions, I thought I might pass out as a result of not breathing, while gradually squeezing the trigger, and waiting for the damn gun to go off. I’ve never had a trigger job on a Marlin, so I really don’t know what could be done. I am also missing half the skin on my right thumb, right next to the nail. Feeding banana size rounds into that little magazine port leaves something to be desired. I need to find my little “JM” hammer spur extender. It is difficult to get a thumb under even a small scope ocular. I guess I need to get a sling, but I’d like to get one that allows the gun to lie flat on my back, rather than with the underside of the lever performing a crude yet persistence form of surgery as I bobble around the countryside.

Bottom line – I like this gun and would and will take it hunting for almost anything, in closely wooded areas. I’ll pick a couple of favorite loads and see if I can index my scope adjustments so I can reliably swap between the loads. For this level of price and performance, it would be hard to do better than the 1895G.

Handloads

These are my handloads, from my gun, with my components. I don’t know if, or suggest, they will work well for anyone else. In fact, these may generate excessive pressure even for other Model 1895G users. They are not, N-O-T, suitable for any other type of rifle, particularly older trapdoor type rifles chambered for the .45-70, or modern reproduction pieces of similar design and strength. They may be okay for bolt action and falling block rifles of superior strength, but I do not know that, nor have I attempted to test or qualify these handloads for this purpose.

IMR4198 and Reloder 7 were no doubt the best performers in terms of accuracy and velocity. Win 748 would not be a future choice. There were no poor performing bullets in terms of velocity or accuracy. One of the best performers were the incredibly cheap bulk Remington 405 grain bullets. With care, and outside of the 748 loads, the gun could shoot .750″ or less groups all day. My three favorite handloads are noted in bold above.

I couldn’t get a huge leap in fps between the 350 and 400 grain bullets. Maybe I was just being too cautious, but it didn’t seem to make sense to push the 350 any faster. The top 405 generated over 3,800 ft/lbs of muzzle energy, the 350 about 3,300, and the 3,000. I think that all works for me in the gun’s intended purpose.

At the risk of further angering the one person who apparently took exception to my indelicate handling of the Shooting Times article on the .450 Marlin; the only thing I couldn’t get out of the .45-70 that they published for the .450 Marlin were the 250 grain loads (I didn’t attempt any), and the high velocity 300 grain bullet loads. Quite frankly, I’m not sure how ST got both the bullet and 63 grains of R7 in that little case. But then, what do I know ?

Great gun and great cartridge – I’ll put up the load data on the home page and look forward to some further experimentation.

More “The Model 1895G”:

The Model 1895G Part I

The Model 1895G Part II

The Model 1895G Part III

The Marlin 1895G – reducing felt recoil

Handload Data 45-70 Gov’t

Thanks,

Joe

Email Notification