An update and interim article – I wanted to select bullets that would function properly in feed and ejection cycles and expand properly at elevated velocity. A week into the process I realized I had no way to make that determination prior to completing the project, so I did what most of us do when confronted with a new situation; opened a catalog to the 45 ACP bullet section, closed my eyes, and stabbed at the page with a pencil 10 times. All an all, I think I faired pretty well in that all of the selections appear to be relatively round and near the correct groove diameter for the 45 ACP.

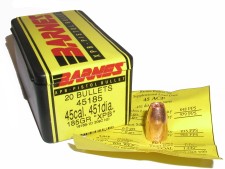

Barnes XPB

When I received the invoice for the project’s Barnes XPB bullets, a thought came to mind for a possible single bullet packaging Barnes might want to consider. At 65 cents per bullet, 20 bullets per box, the XPB is a natural for a limited edition series. Handgunners typically shoot a lot of ammo during the course of a year, making 20 bullets an odd container count and 2,000 rounds of development and practice bullet a pricy proposition at $1,300. The same quantity from virtually every other quality bullet supplier runs in the neighborhood of $180, including Remington‘s Golden Saber. A little higher end, Speer Gold Dots with their excellent field report ratings, would cost $260 for the same quantity. Any way you cut it, there is the price of a new Kimber 45 ACP pistol hiding in the high price of Barnes XPB bullets.

When I received the invoice for the project’s Barnes XPB bullets, a thought came to mind for a possible single bullet packaging Barnes might want to consider. At 65 cents per bullet, 20 bullets per box, the XPB is a natural for a limited edition series. Handgunners typically shoot a lot of ammo during the course of a year, making 20 bullets an odd container count and 2,000 rounds of development and practice bullet a pricy proposition at $1,300. The same quantity from virtually every other quality bullet supplier runs in the neighborhood of $180, including Remington‘s Golden Saber. A little higher end, Speer Gold Dots with their excellent field report ratings, would cost $260 for the same quantity. Any way you cut it, there is the price of a new Kimber 45 ACP pistol hiding in the high price of Barnes XPB bullets.

My previous experience with the X and XLC products, cause me to believe the XPB and other X type bullets for low velocity application may not be tremendously useful. I use them all of the time in hot magnum rifle handloads, where the solid copper alloy shank and nearly closed nose cavity holds up admirably. X bullets for the 30-30 WCF, 45-70 Government and 45 ACP, however, are exceptionally long for their weight as an accommodate of their low sectional density. The result is deep seating and a further loss of already marginal cartridge powder capacity. In addition , the solid bullets seem to require a design induced weakness to assure adequate expansion at low impact velocity. This 185 grain bullet is a good example of both issues.

My previous experience with the X and XLC products, cause me to believe the XPB and other X type bullets for low velocity application may not be tremendously useful. I use them all of the time in hot magnum rifle handloads, where the solid copper alloy shank and nearly closed nose cavity holds up admirably. X bullets for the 30-30 WCF, 45-70 Government and 45 ACP, however, are exceptionally long for their weight as an accommodate of their low sectional density. The result is deep seating and a further loss of already marginal cartridge powder capacity. In addition , the solid bullets seem to require a design induced weakness to assure adequate expansion at low impact velocity. This 185 grain bullet is a good example of both issues.

As 185 grain bullets go, the Barnes bullet is long, .725″ long, compared to .534″ for the Speer Gold Dot pictured left. The Barnes nose cavity is .350″ deep and wide. The Gold Dot’s “V” shaped cavity is .200″ deep, however, because it is cone shaped the wall thickness is greater than that of the Barnes bullet. The solid shank length for both bullets is almost the same. Barnes reloading manuals, at least releases 2 and 3, do not contain handgun data. This is a bit odd because Barnes produces a substantial number of handgun bullets. Inside the box was a little yellow slip sheet labeled “supplemental load data”, featuring exactly two modest handloads. I’m not sure how it is possible to supplement something that hasn’t previously existed; see “Barnes reloading manuals do not contain…” Hmm… Yes, I know I may have just stumbled across the reason Real Guns doesn’t draw a lot of industry advertisers.

Remington

I selected two Remington bullets for this application, a conventional 185 grain jacketed hollow point bullet I routinely buy in bulk, and the 185 Golden Saber home security / law enforcement product. Remington loads the latter in a +P premium load package for the noted use. If you are not familiar with Golden Saber bullets, there are a few interesting approaches Remington took in design. The jacket, harder than copper, is made of brass for tighter control of expansion. The nose jacket has slits, actually the jacket is folded under at each slit and embedded in the lead core. The bullet has two dimensions at parallel surfaces. The shank has a driving band that is barrel groove diameter then, just forward of the driving band the bullet is reduced to bore diameter; a measured .451″ and .442″ respectively. The stated intention of all of this is to have a nose diameter that will align the bullet in the bore while the driving band provides gas sealing to improve accuracy, while increasing velocity through reduced bore friction. OK, I’ll bite.

Speer 260 grain JHP

Not singling out the Barnes bullet for criticism, but because it lends itself to this comparison – The 260 grain Speer with a conventional lead core, copper jacket construction has a shorter overall length than the Barnes 185 grain. The difference, beyond the obvious increase in weight, is that heavy bullets utilize smaller powder charges, so loss of capacity to length is not as significant. I am looking forward to developing more loads around this particular heavy weight as it makes good sense for a high pressure 45 ACP load.

The Usual Suspects

|

Project Bullet selections |

||||||

| Company | Bullet | Type | Grains | Length | Seating Depth | C.O.L. |

| Barnes | XPB | HP | 185 | 0.723″ | 0.391″ | 1.230″ |

| Hornady | HP/XTP | JHP | 200 | 0.569″ | 0.237″ | 1.230″ |

| Hornady | HP/XTP | JHP | 230 | 0.638″ | 0.306″ | 1.230″ |

| Remington | – | JHP | 185 | 0.556 | 0.224 | 1.230 |

| Remington | GS | JHP | 185 | 0.532 | 0.230 | 1.200 |

| Sierra | Sports Master | JHP | 185 | 0.539 | 0.225 | 1.212 |

| Sierra | Sports Master | JHP | 240 | 0.642 | 0.355 | 1.185 |

| Speer | Gold Dot | JHP | 185 | 0.535 | 0.233 | 1.200 |

| Speer | Jacketed | JHP | 200 | 0.547 | 0.290 | 1.155 |

| Speer | Jacketed | JHP | 260 | 0.681 | 0.379 | 1.200 |

There isn’t much I can add to the information appearing in the table at this point. In days gone by, notes on potential feed and ejection reliability would be a topic of presentation. I don’t believe I’ve had a 45 of 1911 design in recent years that did not feed anything loaded, unless it was broken, and I haven’t had a broken 1911 for several years.

Powder Selection

There are lots of powder choices for the 45 ACP for any configuration. I thought I would select powder types that should be close to optimal for the pressure levels and components I’ve selected. The 45 ACP has a case capacity of about 25 grains. Pop in a 240 Grain Sierra bullet and there is barely 11 grains of capacity left over for powder. Capacity is a big consideration.

There are lots of powder choices for the 45 ACP for any configuration. I thought I would select powder types that should be close to optimal for the pressure levels and components I’ve selected. The 45 ACP has a case capacity of about 25 grains. Pop in a 240 Grain Sierra bullet and there is barely 11 grains of capacity left over for powder. Capacity is a big consideration.

I seem to get better results in terms of accuracy and velocity when powder selection results in a nearly full case. In addition, slower powder means larger charges for effect, and larger charges are less sensitive to charge variations; a grain of bullseye produces a lot more energy than a grain of Blue Dot and, therefore, produces greater changes in results with more modest changes in charge weight. The slow powder downside is two fold. Frequently, light bullets require a charge weight that outstrips capacity, and heavy bullets intrude far into a case, again not providing adequate assembled cartridge capacity. The second problem is defined clearly in the documentation that is packaged with QuickLoad, in fact, the section defining QuickLoad’s limitations.

I seem to get better results in terms of accuracy and velocity when powder selection results in a nearly full case. In addition, slower powder means larger charges for effect, and larger charges are less sensitive to charge variations; a grain of bullseye produces a lot more energy than a grain of Blue Dot and, therefore, produces greater changes in results with more modest changes in charge weight. The slow powder downside is two fold. Frequently, light bullets require a charge weight that outstrips capacity, and heavy bullets intrude far into a case, again not providing adequate assembled cartridge capacity. The second problem is defined clearly in the documentation that is packaged with QuickLoad, in fact, the section defining QuickLoad’s limitations.

Many published loads for metallic pistol cartridges include the use of powder designed primarily for shotshell use, powders such as: IMR 700X and 800X, Alliant’s American Select and Unique products, Hodgdon’s Lil ‘Gun, Longshot and Clays are shotshell powders first, but also are useful in handgun cartridges. Not in the context of the companies I’ve just noted, but as a more general concept advanced by the QuickLoad author, shotshell powders are routinely peak pressure tested to 15,000 psi and may not be tested for higher pressures found in handgun cartridges – even when load data is published for a particular cartridge. Some companies don’t test each lot of same type powder, even though powder characteristics may vary significantly from one lot to another. The problem is powder will have predictable peak pressure within ranges.

QuickLoad uses the example of a shotgun powder type that is routinely tested for peak pressure results between 10,000 and 15,000 psi. From a single lot, the powder supplier worked up some handgun loads that operated safely at 25,000 psi, a safe pressure for the handgun cartridge. A new lot of the same powder arrived and again tested safe in the 10,000 to 15,000 psi range. Unfortunately, when the charge was raised to handgun levels, the charge that once yielded 25,000 psi, now produced 60,000 psi.

QuickLoad is not necessarily an effective predictive pressure tool for longer cylindrical case cartridges. Again, as referenced from the QuickLoad documentation where an example of a 308 Winchester and 45-70 Government as being similar in capacity, yet the 308 Winchester produces much greater pressure in a shorter period of time. The explanation is that the primer ignites some powder, but not all, and as the now moving charge heads for the bore, the case shoulder forces powder back into the burning portion of the charge, causing it to ignite.

QuickLoad is not necessarily an effective predictive pressure tool for longer cylindrical case cartridges. Again, as referenced from the QuickLoad documentation where an example of a 308 Winchester and 45-70 Government as being similar in capacity, yet the 308 Winchester produces much greater pressure in a shorter period of time. The explanation is that the primer ignites some powder, but not all, and as the now moving charge heads for the bore, the case shoulder forces powder back into the burning portion of the charge, causing it to ignite.

Without a shoulder, the .45-70 case allows the powder to move unburned past the case mouth and ignite at various points in the barrel where there is a lot more chamber/bore volume to pressurize. Therefore, cylindrical cases tend to generate lower pressures than predicted, under some circumstance. Because this anomaly appears to be proportion to powder column length, I would guess the short 45 ACP case shows less deviation. Which means I really don’t know, I think so, but I wouldn’t venture out without a third method of quantifying pressure.

Conclusion

I can do this, which sometimes comes as a surprise even to me. I’m happy with the powder and bullet selections, primers are always CCI and I have enough test methods and components to put together three pressure levels. The next installment should have some results and hopefully loads at three pressure ceilings.

More “Hyper .45 ACP Loads and the .45 Thuper Revisited”:

Hyper .45 ACP Loads and the .45 Thuper Revisited Part I

Hyper .45 ACP Loads and the .45 Thuper Revisited Part II

Handload Data 45 ACP

Handload Data 45 Super level loads

Thanks,

Joe

Email Notification