I was sitting at my desk, morning stubble on my face, a cup of coffee in my hand, trying to think how to best put Remington‘s .300 Ultra Mag into proper context. In 1969, I was having a few beers down on BC Street in Okinawa with friends, when I first heard the Stones sing “Honky Tonk Woman”. A song about American culture, written by Brits while vacationing on a ranch in in Brazil. In 2006, I heard the Jerry Lee Lewis and Kid Rock concert rendition. The original was OK, but the 2006 version was sensational, and the latter is about how the Remington Ultra Mag plays in the world of thirty caliber magnums.

I was sitting at my desk, morning stubble on my face, a cup of coffee in my hand, trying to think how to best put Remington‘s .300 Ultra Mag into proper context. In 1969, I was having a few beers down on BC Street in Okinawa with friends, when I first heard the Stones sing “Honky Tonk Woman”. A song about American culture, written by Brits while vacationing on a ranch in in Brazil. In 2006, I heard the Jerry Lee Lewis and Kid Rock concert rendition. The original was OK, but the 2006 version was sensational, and the latter is about how the Remington Ultra Mag plays in the world of thirty caliber magnums.

There have been many popular .308″ magnums over the years beginning with the 1925 release of the .300 H&H Super. Some are short .308 Winchester length, some are .30-06 Springfield length and some are full length like the original H&H. The .300 Remington Ultra Mag is full length like the H&H, but larger in body diameter for increased capacity. The information that follows covers live fire performance of the round, rifle and optics, as well as developed handload data. I wrote this in a less than organized fashion, so free to skip around for anything that might be useful. If you find yourself nodding off periodically, that is a normal reaction to my material. One reader described my work as “Incredibly anesthetic…a stream of unconsciousness, rife with inferior monologue”.

Nuance rears its ugly head…

The .30-06 Springfield was used as the comparison piñata within the group as it is the cartridge most thirty magnum buyers wish to trump, in fact, double Donald Trump. No, I don’t know exactly what that means, but then neither do you…so I guess we’re even.

| Cartridge |

Case Length |

Base Dia. |

Shoulder Dia. |

Case Capacity |

180 Grain fps |

BBL Length |

Corrected fps |

Point Blank Increase |

Energy Increase |

| .30-06 Sprgfld | 2.494″ | .4698″ | .4410″ | 68.2 | 2700 | 24″ | 2948 | 289 | 3473 |

| .300 WSM | 2.100″ | .5550” | .5381″ | 81.3 | 3000 | 24″ | 3130 | +17 | +442 |

| .300 H&H | 2.850″ | .5120″ | .4498″ | 85.9 | 3050 | 26″ | 3135 | +17 | +454 |

| .300 Winchester | 2.620″ | .5126″ | .4891″ | 93.8 | 3000 | 24″ | 3183 | +21 | +576 |

| .300 Weatherby | 2.825″ | .5117″ | .4920″ | 98.9 | 3200 | 26″ | 3226 | +25 | +686 |

| .300 Ultra Mag | 2.850″ | .5500″ | .5250″ | 112.5 | 3300 | 26″ | 3259 | +28 | +771 |

| .30-378 Weatherby | 2.913″ | .5871″ | .5610″ | 133.0 | 3300 | 28″ | 3315 | +33 | +846 |

“Corrected fps” reflects theoretical parity by expressing the performance of all cartridges as if loaded to a uniform pressure of 64,000 PSI and utilizing a 26″ barrel standard. No, I am not suggesting the .30-06 Springfield should be loaded to this pressure level, but feel free to ignore this statement, take the information out of context and tar and feather me on a message board. The issue of uniform pressure and barrel length is of consequence because mainstream manuals sometimes leave a false impression of cartridge’s potential. Sierra and Hornady represent the .300 Weatherby, loaded to 65,000 PSI and with a 26″ test barrel. Their listings of the .300 H&H hold pressure to a SAAMI 54,000 CUP U.S. standard, with 24″ test barrel length, rather than applying a CIP 62,000+ PSI ceiling. The result is a 350 fps edge given to the Weatherby. If the H&H is loaded to CIP levels and pushed through a 26″ barrel, the Weatherby edge is reduced to only 91 fps.

To arrive at “Point Blank Range”, I used the Real Guns Exterior Ballistics Calculator, and set the critical target size at 6″. Essentially, “Point Blank Range” begins at the muzzle and terminates at the farthest distance a rifle’s crosshairs could be placed at the center of a 6″ target, with assurance a bullet would impact along the vertical axis of that 6″ circle. The listed .30-06 Springfield load could be fired from a rifle without hold over at any distance from zero to 289 yards and stay within that 6″ target. The .300 Remington Ultra Mag provides 28 more point blank yards for a total of 317. To compensate for the pointblank shortfall, the .30-06 Springfield shooter would only have to raise his rifle’s cross hair 2″, but that isn’t going to get him the additional 561 ft-lbs of energy of the .300 Remington Ultra Mag.

I tape my targets to a five gallon pail of sand and half inch gravel as a non-ricocheting backstop, then I place the bucket in front of another backstop; like several tons of granite and earth. I have popped the same with heavy .375 H&H loads and it mostly just sat there, waiting for me to stop the sand bleeding with a piece of duct tape after each set of a half dozen rounds fired. For some reason, the .300 Remington Ultra Mag was able to push that bucket all over the place.

Making a Buriden’s Ass of myself…

I have tried to elevate my decision making process to the point, “bright” and “shiny” aren’t the two prime consideration when selecting a firearm. I had no prior major investment in any of the .308″ magnums, subsequently I was able to skip over the marginally lower performing thirty magnum versions and focus on the .300 Remington Ultra Mag and .30-378 Weatherby. The performance difference between .30-378 Weatherby and .300 Remington Ultra Mag cartridges is negligible. However, the Remington Model 700 CDL is a really well made and nicely finished rifle, whereas the Weatherby Accumark is a little…rough. The Remington will easily shoot sub MOA in production trim, the Weatherby will not. The Remington has a three round capacity compared to the Weatherby’s two and the Remington weighs a full pound less. The Remington is nearly half the price of the Weatherby. Well, all right then, Remington it is.

I sometimes drift into marketing department vernacular, where adjectives become so overworked I have to resort to multiple explanation marks to show honest enthusiasm for a product. Consequently, when a really solid rifle does comes along, I often find myself groping around at the bottom of an empty accolade barrel. Let’s try this –

There are firearms I metaphorically snooze through in review; inspect, handload, shoot and report. There are firearms that are continually left at the back of the writing queue because they are so boring. Then there are rifles I have a difficult time writing about, because I have too much fun shooting them, like the Remington CDL. In the case of the Remington Model 700 CDL Ultra Mag, I set the chronograph and calculator aside for a couple of days and drove 78 miles just so I could shoot some two hundred yard targets. Wringing out the combination of Remington Model 700 CDL rifle and Bushnell Elite 6500 scope was…fun. I developed a real respect for the combination as one that can deliver lots of power down range, but also one that is easy to shoot with accuracy!!!…!!..!

On the benefits of wince free shooting…

I find the best way to qualify degree of recoil with an unfamiliar firearm is let one of your grown sons shoot it first with proper motivating statements like, “It hardly kicks. You’re mother shoots it all the time”. Notice the rifle, under discharge, is still laying in the rest. We tend to go all out on equipment, those are two of Home Depot’s, best folding plastic saw horses, topped with a piece of 3/4″ plywood I rescued from a project…I was suppose to complete last winter.

Between a bit of sporter heft and the rifle’s R3 recoil pad (Limb Saver), recoil is quite easy to handle, more of a push than a jab, at approximately 37.3 ft-lbs. Yes, even when I was the one pulling the trigger. The slight 1⅜” drop at the heel of the stock keeps muzzle jump in the category of minor. Under recoil, the rifle comes straight back and remains pretty much on target. Quite a contrast to the .500 Jeffery that tossed me around like Daffy Duck shooting a Thompson submachine gun. Report isn’t minor, and it is perhaps a little protracted, but it definitely lacks the annoying pressure wave concussion generated by some of the other large cartridges. I wore a set of 29 db reduction hearing protectors during live fire and found myself, at the end of two days of intensive shooting, without a pounding headache or responding to every question with, “Huh?” or “Whut?”.

The Remington Model 700 CDL’s weight, for a standard 26″ profile barreled gun, is not exceptional. The combination of rifle, high power Bushnell Elite 6500 scope and Brownells‘ Latigo sling came to 9 lbs 5 oz. I could easily bring this weight down to 6 lbs 5 oz, and not increase felt recoil, by pushing away from the dinner table five minutes sooner.

200 Yards is really far with real bullets…

The Bushnell Elite 6500 Scope and Warne mounts proved to be a really good pick. The scope didn’t shake out of adjustment. The cross hairs are a great color, they are easy to see, but they aren’t distracting. For the first time, in I don’t know how long, I could move a couple of clicks and the follow holes in the target moved right along with them and the increment of shift didn’t amplify or diminish with increased adjustment. The eye relief was excellent. No bumped eyebrows and no stock climbing required. I was shooting so well with the scope I actually changed off from a Latigo sling to a Brownells‘ 1¼” Competitor Plus Sling so I could shoot distance from several positions. I was happy with the results. Knowing I could shoot 3″- 5″ at 200 yards from a sitting position with a sling is a great confidence builder for hunting. I’ve learned to use almost anything growing out of the ground for a rest; animal, vegetable and/or mineral.

Parallax was easy to adjust out while looking through the Bushnell scope and the index on the scope pretty much matched up with an eye check for shift. Frequently, scopes are off more than a full index step during adjustment. I shot at 2.5x, I shot at 16x; the image was just as sharp and bright. I know that on the Internet everyone takes running shots at 500 yards. I’m just not that good. 200 yard targets are a ways off for me, so when I shoot well, the quality of the optics I am looking through has a lot to do with the results. I shot 200 yards at 10x, the default Mil Dot sync magnification and that worked out really well. The space between dot centers is one mil, or approximately 3.6″ at 100 yards and a hair over 7″ at 200 yards. It didn’t take long to get a brain scope connection going that made adjusting for distance and estimating the size of objects second nature. Discerning half and quarter mill positions also became easy. Estimating target size is pretty spiffy as long as the shooter has a general sense of distance. If you’re at all good at judging distances, the difference of 50 yards won’t make or break you. If you are plus or minus two hundred yards, that might get you seeing 48″ tall bunnies. Practice, practice, practice…or get a range finder. The one closing note I would make on this scope, and it speaks directly to the scope’s quality, when I pulled it from the rifle and removed the tightly secured rings, there was not a scratch, mark or impression left in the finish. It looked just as it did when it come out of the box.

Bullet points…

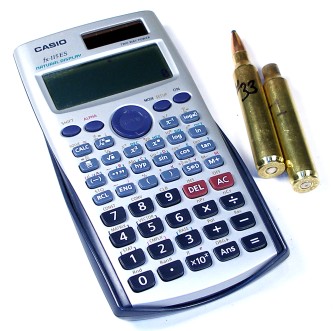

Bullet performance at elevated velocity can get a little dicey. The Remington CDL was fairly accurate across the weight range from 125 grains to 200 grains, however, it seemed to become exceptionally accurate from 165 grains up. The best 100 yard groups came from the least expensive and the heaviest bullet. The best 200 yard groups came with Barnes bullets. The best performing bullets, in terms of expanding and holding onto weight at any distance came from Barnes Delrin tipped TTSX bullets. I don’t know what they do in treating the alloy they use for their bullets, or what treatment they receive afterward the mechanical production steps, but I have never seen copper this malleable hang together so well when pushed this hard. They are from left to right – Barnes TTSX 130, 150, 168, and 180 grain. Barnes MRX 150, 165 and 180 grain. Remington 125 grain.

Bullet performance at elevated velocity can get a little dicey. The Remington CDL was fairly accurate across the weight range from 125 grains to 200 grains, however, it seemed to become exceptionally accurate from 165 grains up. The best 100 yard groups came from the least expensive and the heaviest bullet. The best 200 yard groups came with Barnes bullets. The best performing bullets, in terms of expanding and holding onto weight at any distance came from Barnes Delrin tipped TTSX bullets. I don’t know what they do in treating the alloy they use for their bullets, or what treatment they receive afterward the mechanical production steps, but I have never seen copper this malleable hang together so well when pushed this hard. They are from left to right – Barnes TTSX 130, 150, 168, and 180 grain. Barnes MRX 150, 165 and 180 grain. Remington 125 grain.

Based on results from the recent .30-06 Springfield project, I spent more time on short distance bullet recovery. Using a large container of sawdust and silt, a variation on the Folgers Test, I had the opportunity to see how bullets perform when stressed outside of design parameters for impact velocity. No, I am not being a pinhead and conducting unfair tests. I just wanted a way to sort out the toughest bullets that would expand to form the largest wound channel, in the event game doesn’t cooperate and show up at a distance prescribed by the bullet manufacturer. The pile of lead and copper jacket shards on the left were once the lead core jacketed bullets listed in the handload data. The bullets on the right are all of the Barnes Delrin tipped TTSX slugs. Only one of the TTSX bullets broke apart, one particular 130 grain load that was way over the top. I cut velocity by 75 fps and even this flyweight held together. I did not run this checkout with Barnes MRX product. They are specifically designed for long range shooting with a nose configuration that will upset and mushroom completely at 200 yard velocities.

Handloads…Do these primers look flat to you?

Before someone gets into a tizzy about the 130 grain load data that follows, that .220 Swift look alike load below was derived from a maximum load from the current Barnes manual, data which is predicated on shooting through a 24″ barrel in comparison to the Remington’s 26″ barrel. Please feel free to check the Barnes manual and let it speak for itself in terms of primer selection, COL, etc. I am not assigning them responsibility for my versions. There were no signs of excessive pressure in case and primer readings, no sticking bolts and strain gauge readings were not out of line with an acceptable warm load results.

Before someone gets into a tizzy about the 130 grain load data that follows, that .220 Swift look alike load below was derived from a maximum load from the current Barnes manual, data which is predicated on shooting through a 24″ barrel in comparison to the Remington’s 26″ barrel. Please feel free to check the Barnes manual and let it speak for itself in terms of primer selection, COL, etc. I am not assigning them responsibility for my versions. There were no signs of excessive pressure in case and primer readings, no sticking bolts and strain gauge readings were not out of line with an acceptable warm load results.

QuickLoad was not useful as an analysis tool for light bullets. Pressure results were significantly overstated and bullet length data is off considerably. As an example, the Delrin tipped 150 grain TTSX is listed as 1.283″, but is actually 1.208″. I triple checked standard load data from bullet manufacturers and powder suppliers against QuickLoad calculation and QuickLoad would consistently show 85,000 PSI for routine mainstream manual loads that showed no signs of excessive pressure in practice. My guess is something buggy in the coefficient of friction variables at the low end as weights. Bullets above 130 grains got progressively closer to manual data to the point 165 grain was a match and very, very close in velocity projections. When I get a chance I will get back to this issue. Oddly enough, I could understand the Barnes bullet with driving bands and lower bore friction might step outside the normal model for pressure, but other conventional shank bullets demonstrated similar high results with QuickLoad.

| Bullet Type | Bullet Weight | Net Water Capacity | COL | Powder Type | Powder Charge |

Calculated Muzzle Velocity |

Actual Muzzle Velocity |

| Barnes TTSXBT | 130 | 104.8 | 3.600 | Re 22 | 99.5 | 3692 | 3908 |

| Re 25 | 104.5 | 3722 | 3794 | ||||

| MagPro | 106.5 | 3724 | 3869 | ||||

| Barnes TTSXBT | 150 | 100.3 | 3.600 | Re 22 | 95.5 | 3505 | 3617 |

| MagPro | 100.0 | 3503 | 3622 | ||||

| 7828SSC | 95.5 | 3476 | 3604 | ||||

| Barnes TTSXBT | 168 | 100.2 | 3.600 | Re 19 | 90.5 | 3321 | 3454 |

| Re 22 | 91.5 | 3343 | 3366 | ||||

| RS Magnum | 102.5 | 3333 | 3457 | ||||

| Barnes TTSXBT | 180 | 99.1 | 3.600 | Re 22 | 87.0 | 3153 | 3170 |

| Re 25 | 90.0 | 3151 | 3115 | ||||

| RS Magnum | 98.5 | 3176 | 3286 | ||||

| Barnes MRX – BT | 150 | 103.6 | 3.575 | Re 22 | 95.5 | 3505 | 3534 |

| MagPro | 100.0 | 3503 | 3577 | ||||

| 7828SSC | 95.5 | 3476 | 3587 | ||||

| Barnes MRX – BT | 165 | 102.1 | 3.575 | Re 19 | 90.5 | 3321 | 3455 |

| Re 22 | 91.5 | 3343 | 3382 | ||||

| RS Magnum | 102.5 | 3333 | 3501 | ||||

| Barnes MRX – BT | 180 | 101.3 | 3.600 | Re 22 | 87.0 | 3153 | 3177 |

| Re 25 | 90.0 | 3151 | 3115 | ||||

| RS Magnum | 98.5 | 3176 | 3305 | ||||

| Hornady BTSP Interlock | 190 | 101.9 | 3.575 | Re 25 | 92.5 | 3096 | 3201 |

| H1000 | 93.5 | 3070 | 3099 | ||||

| 7828SSC | 89.0 | 3112 | 3211 | ||||

| H870 | 104.0 | 3155 | 3197 | ||||

| Nosler AccuBond | 200 | 98.6 | 3.600 | Re 22 | 87.0 | 3060 | 3096 |

| Re 25 | 88.0 | 2999 | 3023 | ||||

| 7828SSC | 87.5 | 3098 | 3152 | ||||

| MagPro | 90.0 | 3056 | 3107 | ||||

| Prvi PSP | 165 | 103.7 | 3.541 | Re 22 | 89.0 | 3172 | 3323 |

At least they stop the load sheets from blowing away… Whenever I set up to record data, I always drag out enough instrumentation to check wind velocity, temperature, humidity, hardware temperature changes and velocity. Personally, I was very impressed by the spinning wheels, flashing LCD’s and trying to get the little red dot from the Fluke infrared thermometer on a spot that was reflective enough to be accurate. What did I learn?

Whenever I set up to record data, I always drag out enough instrumentation to check wind velocity, temperature, humidity, hardware temperature changes and velocity. Personally, I was very impressed by the spinning wheels, flashing LCD’s and trying to get the little red dot from the Fluke infrared thermometer on a spot that was reflective enough to be accurate. What did I learn?

Ambient temp climbed from 69°F at noon to 82 °F at 2:30 PM without effect on accuracy. Humidity went from 32% to 22% and that…made no difference. Three shots through the barrel within one minute, at one point, raised temperature from 68°F to 85°F which also had no bearing on accuracy or apparent pressure. Finally, three more shots within another minute pushed breech barrel temperature to 92°F. Now that, that…had also no measureable effect on performance. OK, so I will conclude with these little instruments are colorful and can suggest intelligent consideration, they did no more than underscore the cartridge’s and rifle’s lack of sensitivity to temperature or humidity…or at least with the powder and primers selected. Good for South Dakota hunters who can enter the Black Hills in the dead of winter and leave in the afternoon with the presence of Spring.

Yes, but did you hit anything…

This was the best three shot 100 yard group. It was shot by my son who was incredibly lucky,

This was the best three shot 100 yard group. It was shot by my son who was incredibly lucky,  apparently three times in a row. Hey, if I could see and I still had hair I could have done as well. The group is less than ½” and he did it more than once. Of course it was the magic of my great handloads and exotic components that made it all possible…the cheapest PRVI PSP 165 grain bullets and a moderate load of Re22.

apparently three times in a row. Hey, if I could see and I still had hair I could have done as well. The group is less than ½” and he did it more than once. Of course it was the magic of my great handloads and exotic components that made it all possible…the cheapest PRVI PSP 165 grain bullets and a moderate load of Re22.

The second smallest group was tied between the Hornady 190 grain slug at 0.60″ group and the Nosler 200 grain Ballistic Tip at 0.80″, but the Barnes TTSX were very close also.

I’m not a long distance shooter, but this was the best of shooting off of a rest at 200 yards. The five shot group on the right is under 1.3″ and it was shot with Barnes MRX 168 grain bullets. The 2.3″ group to the far right was shot with Barnes 180 grain TTSX bullets.

I’m not a long distance shooter, but this was the best of shooting off of a rest at 200 yards. The five shot group on the right is under 1.3″ and it was shot with Barnes MRX 168 grain bullets. The 2.3″ group to the far right was shot with Barnes 180 grain TTSX bullets.

The five shot 1.7″ 200 yard group, left, was shot with 180 grain MRX bullets. The subject was covered in more depth in Part I, but the notion of heavier than lead core with it’s center of pressure shifted aft to provide increased stabilization about the bullets longitudinal axis seems to work well. Again, I am not a 200 yard shooter, but being able to put together groups like this is a great hunting confidence builder.

My conclusion with bullets is that hundred yard accuracy and tight groups are possible with virtually any popular commercial bullet, 200 yards and beyond could benefit from a special purpose bullet like the Barnes MRX product. They are pricey, but then they are for special purposes and conditions and worth the increased performance they can provide. In terms of hunting bullets, at this level of velocity and inside two hundred yards, I think the Barnes TTSX products would provide a lot of peace of mind when it comes to proper expansion and high levels of retained weight.

Copious notes and other mental wandering…

I’m not a precision handloader in the respect that I do not have a list of meticulous steps I work through universally for every cartridge. I always do the basics, which are more for safety than quality, but there are lots of finesse steps that have no effect on some cartridges and I don’t have a lot of time to waste…as I seem to waste it in so many other areas. So I try to identify what other precision steps are key to a cartridge’s personality.

The .300 Ultra Mag is a well behaved cartridge; predictable and consistent. That said, it is also a cartridge that responds significantly to the degree of care introduced into the handloading process in some areas. The cartridge has so much long range potential, it was only fair to try to do my part to give the cartridge a chance to do its job.

The .300 Ultra Mag is a well behaved cartridge; predictable and consistent. That said, it is also a cartridge that responds significantly to the degree of care introduced into the handloading process in some areas. The cartridge has so much long range potential, it was only fair to try to do my part to give the cartridge a chance to do its job.

Brass Prep

I began with new Remington Brass. Case length was 2.841″ +0.003″/-0.000″ compared to a case spec of 2.850″ +0.000″/-0.020″. The chamber spec to the case mouth is 2.860″ so there was little chance of the case mouth binding at the far end of the chamber, jamming a bullet and pressure spiking a handload.

The new brass case mouths were out of round, rough and had a distinct flare. Which is why all brass, regardless the source, needs to be prepped and sized. To get to square mouths and uniform necks, I ran all brass through a full length sizer and trimmed everything to 2.837″ +0.001″/-0.000″. SAAMI minimum length spec is 2.830″. There are other reasons for cutting a case mouth square. I used Hornady Custom Grade New Dimension Dies. The full length seater has a floating alignment sleeve that is designed to bring the bullet in concentric alignment with the case centerline.

The alignment sleeve diameter that slips over a case neck is 0.348″, the spec for brass is 0.344″ +0.002″/-0.000″ and the chamber spec is 0.346″ +0.002″/-0.000″. Raw Remington brass measured 0.350″ and was significantly flared at the mouth. The sleeve’s neck recess won’t form the neck to brass spec, but neck containment should at least insure the round will chamber after passing through this die. If no crimp is applied, between the sizer and the seater dies, assembled ammo will have a neck outside diameter of only 0.336″. Of greater consequence for bullet – case concentricity is the case mouth contact surface.

The alignment sleeve diameter that slips over a case neck is 0.348″, the spec for brass is 0.344″ +0.002″/-0.000″ and the chamber spec is 0.346″ +0.002″/-0.000″. Raw Remington brass measured 0.350″ and was significantly flared at the mouth. The sleeve’s neck recess won’t form the neck to brass spec, but neck containment should at least insure the round will chamber after passing through this die. If no crimp is applied, between the sizer and the seater dies, assembled ammo will have a neck outside diameter of only 0.336″. Of greater consequence for bullet – case concentricity is the case mouth contact surface.

The ridge inside the sleeve, cleverly marked “Case Mouth” at the right, is set into the sleeve only far enough to allow 0.185″ of the 0.306″ long neck to enter the sleeve. When the case is driven upward into the die, the case mouth contacts the ridge inside the alignment sleeve and bares all of the force required to seat the bullet in the case neck. Without case trimming to square the case mouth to the alignment sleeve, I could get bullet concentricity of 0.007″. With case trimming and the case mouth square to the ridge in the alignment sleeve, 0.002″-0.003″ was easy to attain.

Establishing COL…

I typically use a Stoney Point, now Hornady, COL gauge when I work with a new combination to determine how much dimensional latitude I have when handloading. If you’re interested in the subject, we made some cutaways and offered some information on the subject earlier. The process isn’t complicated, but illustration always helps. In this case, I didn’t have a .300 Ultra Mag modified case so I made one. Considering the price, it is easier to buy one, but if you don’t have one handy and you’re in the middle of a project… All you need to do is run a “K” drill through a case’s primer pocket and follow through with a 5/16″ – 36 tap, then chamfer the hole so there is no raised surface for the gauge to bump into. If you have a hard time locating a tap you can pick one up from Encofor a couple of dollars. I use a once fired case with the case mouth reamed out enough to allow a bullet to move with little resistance. I use an adjustable reamer, also from Enco, that cost about $15. If you just expand the case neck to allow a slip fit with a bullet, the neck will be too large to chamber.

Personally, in a case this large where powder capacity is not a limiting handload factor, I mostly check for sufficient bullet to rifling clearance for blunt, long ogive bullets and sufficient seating depth for light weight bullet. I don’t subscribe to the notion of seating out to the rifling where guns have healthy throats. The spec for a .300 Remington Ultra Mag is a .309″ throat, transitioning to a .308″ groove diameter. There isn’t much room for a right turn in there and, if you clean barrels as I do, there’s always enough gunk in the barrel to keep a bullet straight. For the heck of it, I flipped a bullet around in the test cartridge and closed the bolt. Then I measured the overall length and subtracted the case length spec. The Remington’s free bore, the clear area ahead of the case mouth, prior to the rifling leade measured 0.195″ so this isn’t a limiting factor in bullet seating. By measurement, a handloader will run into the magazine box’s forward wall before running out of rifling clearance. From what I can see, the .300 Remington Ultra Mag has two working lengths, lead core bullets below 200 grains and Barnes MRX at 3.575″ COL and everything else at 3.600″. No, I am not suggesting handloaders ignore other published specs, I am just indicating that, like “Ground Hog Day”, one of the worst Billy Murray movies ever made, the two numbers will show up over and over and over…and over again.

Personally, in a case this large where powder capacity is not a limiting handload factor, I mostly check for sufficient bullet to rifling clearance for blunt, long ogive bullets and sufficient seating depth for light weight bullet. I don’t subscribe to the notion of seating out to the rifling where guns have healthy throats. The spec for a .300 Remington Ultra Mag is a .309″ throat, transitioning to a .308″ groove diameter. There isn’t much room for a right turn in there and, if you clean barrels as I do, there’s always enough gunk in the barrel to keep a bullet straight. For the heck of it, I flipped a bullet around in the test cartridge and closed the bolt. Then I measured the overall length and subtracted the case length spec. The Remington’s free bore, the clear area ahead of the case mouth, prior to the rifling leade measured 0.195″ so this isn’t a limiting factor in bullet seating. By measurement, a handloader will run into the magazine box’s forward wall before running out of rifling clearance. From what I can see, the .300 Remington Ultra Mag has two working lengths, lead core bullets below 200 grains and Barnes MRX at 3.575″ COL and everything else at 3.600″. No, I am not suggesting handloaders ignore other published specs, I am just indicating that, like “Ground Hog Day”, one of the worst Billy Murray movies ever made, the two numbers will show up over and over and over…and over again.

If you can’t get better, load a bigger round…

In general, handloads for the Ultra Mag should perform better than smaller cartridges. The mechanical tools, dispensing and scaling equipment have a tolerance that is not measured as a percentage of total, but in more absolute terms. As an example, if a scale will deliver two tenths of a grain accuracy up to 150 grains or so, a two tenths variance on a .223 Remington handload is 1% error, however, with the .300 Ultra Mag with 5x the capacity, the two tenths is only 0.2% error. So, basically, I think we are saying that handloaders who are less than precise should just start handloading a larger cartridge to improve the quality of their production. Yes, I am kidding. Did you see my work on the .500 Jeffery?

A case in search of a better powder…

There are a number of powders that work well with the .300 Ultra Mag. I picked a handful that would provide the greatest bullet weight coverage and the most full cases. I did not identify one that worked consistently best even with similar bullet weights and bullet geometry. The Ultra Mag could use a slower powder. The capacity offers an opportunity for longer pressure persistence and the 26″ barrel length should be able to take advantage of this increase. This is the first cartridge in a very long time that responded well to MagPro and Magnum. Good results with what is out there, but when you can’t fill a case with Re25 or H870, there is room for something slower.

Good brass life…

| Case | Case Length | Neck | Shoulder | Case Head |

| New-Sized | 2.841 | 0.343 | 0.522 | 0.547 |

| Max Loads | 2.841 | 0.348 | 0.528 | 0.549 |

| Moderate Load | 2.840 | 0.346 | 0.527 | 0.549 |

The dimensions noted above are an average of ten pieces of each category, however, there was a lot of uniformity from one example to another. Five firings of each type showed no significant change to these numbers, although I would suggest annealing brass before it rings like a bell when struck.

I ran into out of stock conditions at leading suppliers during the course of this project. Checking with Remington, the shortage was caused by high demand for loaded ammunition and the popularity of their more recent managed recoil products. Be patient.

So what do we have here?

Hmm… I believe the .300 Remington Ultra Mag is a well engineered cartridge. If you climb into a new generation Ferrari, the first thing that comes to mind, besides the sticker price, is how so much performance could be packed into a civilized package. They start up and idle like a Honda, but scoot down the road pushing the little 263 CI engine to 8500 RPM and 490 HP. The Remington Model 700 CDL and .300 Remington Ultra Mag cartridge really put it out there when it comes to power, but it is a civilized combination to shoot. Performance isn’t sensitive to environment, no degradation at temperature and humidity extremes. Recoil isn’t severe, the barrel doesn’t begin to glow red after a handful of shots and the gun is comfortable to hold point and shoot. It is just a really solid heavy hitter and I’d say I found my third North American rifle to fill the big and dangerous game slot.

Remington’s Model 700 CDL 300 Ultra Mag Part I

Remington’s Model 700 CDL 300 Ultra Mag Part II

Email Notification