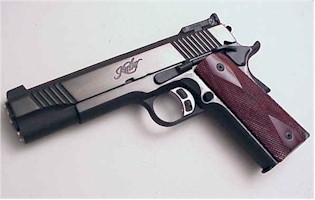

Since my last article, I was able to spend some time going over the Kimber, running some comparisons with a short barreled Officer’s model Colt, and developing a better understanding of the gun. As a result, some of the points made collectively by articles covering the .45 Super® became more understandable, some appeared to be inconsistent.

The Kimber package includes a fiber filled plastic bushing wrench, sturdy and no scratches to the gun’s finish on disassembly, a small flat sight adjusting screw driver and an Allen wrench for the grip screws.

The Kimber package includes a fiber filled plastic bushing wrench, sturdy and no scratches to the gun’s finish on disassembly, a small flat sight adjusting screw driver and an Allen wrench for the grip screws.

Like virtually all 1911 models, the barrel bushing is rotated clockwise, the recoil spring plug is carefully eased out of the slide until the pressure is unloaded, then the plug and recoil spring are removed and set aside. The spring has a closed loop and open loop end. The open loop end is positioned against the recoil spring plug.

The Kimber Gold Match has a solid barrel bushing that is hand fit to a stainless barrel. Nice fit. With the bushing rotated out of the way, the hammer is then cocked, and the slide is brought back until the semicircle of the slide stop tab is under the semicircle cut into the slide. Next, the slide stop is pushed out, and the slide is moved forward and off of the frame. The bushing is rotated counter clock wise and out of the frame, then the barrel is pulled forward and out of the slide. About one minute from the turn of the bushing to an organized pile of parts.

Based upon recent experience, I can only believe the new method for a manufacturer to prepare a gun for shipment, begins with a dunk in a vat of WD 40. I wiped off some of the gunk and took a look at chamber support of the brass cartridge, the slide, then put each part under a magnifying lamp to examine the quality of machine work and part finishing. The gun is well made. No rough parts, very tight fit and lock up of barrel lugs, smooth finishes, and sharp edges broken. I remained as pleased with the Kimber as I was before I had a chance to look inside.

Knowing that .45 Super® conversion companies wouldn’t modify a gun with an Officer length slide, I wanted to see what slide weight differential would qualify a gun as acceptable or unacceptable for conversions. The Kimber slide weighted in the same as the one on my Colt Gold Cup. At 10.4, oz The Officer’s Model was 3.4 oz lighter. I started playing around with numbers, slide weights and muzzle velocity, and I think I understand 30lb spring used in the .45 Super® conversion kits.

The recoiling slide energy increases as the square of the velocity. The velocity of the 185 grain bullet in the .45 ACP is approx 940 fps. The .45 Super® 185 grain velocity performance is approximately 1300 fps, or about a 38% increase for the .45 Super®. The 38% increase in velocity would result in a 90% increase in opening slide energy. The standard spring for the government model is 16 lbs. A corresponding 90% increase in spring rate would be 30 lbs. As an alternative, they may have just kept upping spring rates until the slide stayed on the gun.

I tried to come up with a more absolute relationship between slide weight, bullet weight, bullet velocity and spring rates, but I couldn’t. The answer kept coming up as 10 lbs, but because I hadn’t taken into consideration friction or energy lost to mechanical actuation, the result should have been higher than 16 lbs. I need to think about that a little bit more.

I had an opportunity to place the cutaway cases in the Kimber barrel, headspace on the case mouth and see how much more protection the .45 Super® offered. As you can see, there is still powder cavity beyond the closed portion of the barrel and well into the feed ramp.

I had an opportunity to place the cutaway cases in the Kimber barrel, headspace on the case mouth and see how much more protection the .45 Super® offered. As you can see, there is still powder cavity beyond the closed portion of the barrel and well into the feed ramp.

The .023 thicker web represents 13% more material, which is significantly better than a standard or +P case. and offers a greater pressure safety margin.

The Kimber operating manual, less than exciting, cautioned against handloading, suggesting the effort required great expertise, and the use of handloads in the Kimber would void the warranty. On the other hand, I believe that handloads made with reasonable care will always out perform factory ammo. I decided I would conduct tests with carefully selected handloads, working up from .45 ACP levels through the top .45 Super®, recording results throughout the process. But first….

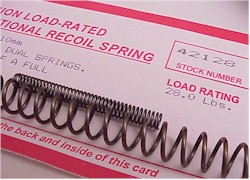

Springs

No matter how I looked at this conversion, the key elements were obviously springs; recoil and firing pin. The ability for the gun to handle a decent selection of loads, while remaining reliable in operation, would be determined by the spring selection.

No matter how I looked at this conversion, the key elements were obviously springs; recoil and firing pin. The ability for the gun to handle a decent selection of loads, while remaining reliable in operation, would be determined by the spring selection.

While Wolff Gunsprings does not catalog a spring set specifically for the .45 Super®, they produce a broad selection of spring rates for 1911 type pistols. I felt, based on earlier research on conversion kits and gun modifications, I could find what I needed within their catalog listings. Since the Kimber takes the same spring as the Colt government model, I had a full range of extra power rates to choose from, 22lbs through 28 lbs.

The Wolff 28lb spring, and companion firing pin spring, were originally intended to replace the double spring in the 10mm Colt Delta. This became my starting point. Whenever springs are changed, it’s always best to start with the high end of the range. Worst case, you’ll get a failure to extract / eject, or maybe a stove pipe jam when the empty doesn’t clear the port. So you pop the gun open, drop down to the next lightest rating, and try it again. If you begin your selection from the light side of spring selection, you run the risk of hammering the slide and frame and causing damage, before you get to the correct selection.

How do you know when you’ve got it right ? If the empties get tossed about 3 to 6 feet from the gun, the recoil spring is just about right. If casings are going much farther, it would be appropriate to move up to the next spring rate. If empties are ending up at your feet, you may want to go to the next lighter spring. Not rocket science, but a tried and true method. Once again, the Wolff site is a great source of spring information, and a spring tune can bring a major improvement to your favorite gun.

It’s pretty common to find double springs in auto pistols that require heavy spring rates, or guide rod kit suppliers offering dual springs as a part of their products. Wolff can frequently supply a single spring that will do a better job.

It’s pretty common to find double springs in auto pistols that require heavy spring rates, or guide rod kit suppliers offering dual springs as a part of their products. Wolff can frequently supply a single spring that will do a better job.

Dual concentric springs may coil bind, and two springs will wear and fatigue at different rates, both conditions causing erratic effective spring rates. The single spring approach adds a considerable amount of reliability and consistency of operation to an auto pistol, and at a lower cost.

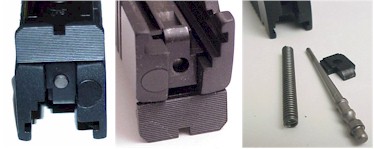

The use of an higher rate firing pin spring, in conjunction with a higher rate recoil spring is critical. Wolff ships recoil and firing pins springs as sets. The issue is that the heavier recoil spring will cause a more harsh slide return, so when the slide hits the end of its forward travel the firing pin’s inertia could keep it moving forward, possibly striking the newly chambered round. A firing pin spring, matched to provide a proper offset to a specific recoil spring, minimizes the chance of this happening. Changing the spring is easy, requiring no more disassembly than would be done during routine cleaning.

I always keep a plastic soldering aid around for poking at pins to avoid marring the finished surfaces of the gun, however, a pen or pencil can work just as well when disassembling a slide. The rear of the firing pin, the silver colored surface protruding through the firing pin stop at the rear of the side, is depressed enough to permit the firing pin stop to slide down. As the stop is removed, it’s important to keep a thumb over the firing pin, which is under spring pressure. With the firing pin stop out of t he way, the firing pin is eased out, along with the spring. The springs are swapped to the new heavy unit, and everything is put back in the reverse of how it was removed.

Back together again, and no leftover parts – alright ! The springs fit correctly, the gun’s function was fine and, with an increase in effort required to cycle the slide, the front serrations started to make a lot of sense. I moved on to work out the loads I would use for checking out the gun. I thought I’d start with standard .45 ACP high velocity 185 grain loads, move up to a +P Cor-Bon 185, on to the equivalent of a tactical .45 Super®, then if I was still holding a complete gun, move up to some max .45 Super®.

.45 Super® Case Capacity

The “Load From a Disk” database lists the .45 ACP at 27.2 grains of full case capacity (water), and net at 18.3 grains with a Speer 185 grain Gold Dot. However, the .45 Super® has a thicker web which should show as a decrease in capacity . Since there is excess case capacity in the .45 ACP, the slight loss of case capacity in the .45 Super® should be of little consequence, but I thought a measurement might give me some further insight into the degree of additional case strengthening that went into the .45 Super®. It’s a pretty quick process, especially if you have a program like “Load from a Disk” that takes care of the displaced volume of a cylinder calculations, etc.

All you need is:

All you need is:

– Small pouring container

– Scotch tape

– Samples of applicable brass and bullet combinations

– A decent powder scale

– Calipers

– A cleaning rod or any rod made of soft material

– The gun the ammo will end up in

– A shop radio – this stuff could get tedious

Essentially, you weigh each case and record the data; first empty, then filled with water. Surface tension will tend to lift the water level above the case level, so you’ll probably want to run something flat across the surface to level fill the cases.

Essentially, you weigh each case and record the data; first empty, then filled with water. Surface tension will tend to lift the water level above the case level, so you’ll probably want to run something flat across the surface to level fill the cases.

You may notice the new brass seems take on a lot of water, perhaps several quarts. It’s very important to seal the primer flash hole before pouring. I just stick a small piece of Scotch tape inside, over the flash hole.

The last three data collecting steps are: measure the overall case length, measure the overall bullet length, then measure the barrel length. The last part requires extra caution. Make sure a mag isn’t in place and the chamber is empty, then close the slide. Insert a rod down the barrel until it makes contact with the recoil face of the slide, that flat area the firing pin pokes through, then place a mark on the rod at the point the rod exits the barrel, and measure that length. I like to use the well known BIC barrel length rod, which is especially made for this purpose. The BIC rod also comes in handy when I have to jot down notes.

If you don’t have software to do your calculations for you, the manual stuff looks like this –

W = S * D2 * 198

W = Weight of water displaced by the bullet in grains

S = Seating depth in inches

D = Diameter of the bullet in inches

You get to “S” by measuring the bullet length, measuring the case length, then adding the two numbers. Then you subtract the spec for the overall cartridge length and the remainder is the seating depth. Generally, you can fill and weigh the case to get the gross capacity, however, the bullet when seated will displace some of the water which will result in a net capacity, or the amount of space left for powder after the bullet is properly seated. The ogive, or tapered profile of the bullet, is forward of the bullets seating area, so the portion inserted into the case is a parallel sided cylinder. The formula calculates the volume of that cylinder and converts the volume to the equivalent weight of water. That amount is then subtracted from the gross water capacity to get to net capacity.

The cutaway on the right illustrates the bullet displacement, as well as one of the reasons I go through these trivial verification steps when I start shooting or loading a new cartridge. The cutaway and the caliper are set to the correct overall cartridge length for a 185 grain bullet in a .45 ACP case. The .45 Super® is externally identical to the .45 ACP. The spec is 1.20″, yet the Triton load data, as well as virtually every article written on the .45 Super® indicates that a 2.220″ overall length is critical.

The reality is you can’t get there from here, the dimension stated in these article is incorrect, and all were obviously based on the same source document error. Unfortunately, in the case of the .45 Super®, there was also the other side of the problem; no two articles agreed on recoil spring rates, with specs cited from 28 – 32 lbs. My point is (as I wander far away from the subject of case capacity) not to focus on someone else’s errors, but rather to illustrate the need to independently test, try and verify. This applies especially to load data, start light and work up.

| Case Type and Mfg |

Case Length |

Bullet Weight-Type |

Bullet Length |

Bullet Dia” |

Case Wgt Grains |

Wet Case Grains |

Gross Capacity Grains |

Net Capacity Grains |

| .45 ACP Rem | .888″ | 185 Gr JHP | .556″ | .451″ | 89.9 | 115.5 | 25.6 | 15.7 |

| .45 ACP Win | .889″ | 185 Gr JHP | .556″ | .451″ | 80.2 | 107.6 | 27.4 | 17.5 |

| .45 ACP +P SL | .896″ | 185 Gr JHP | .556″ | .451″ | 93.2 | 120.1 | 26.9 | 16.8 |

| .45 Super SL | .894″ | 185 Gr JHP | .556″ | .451″ | 89.8 | 114.7 | 24.9 | 14.8 |

| .45 ACP Nominal | .895″ | 185 Gr GD | .568*” | .451″ | na | na | 27.2 | 18.4 |

* .45 Cal Speer Gold Dot bullets from three lots actually measured .535″ in length and they have a concave base to further complicate the issue. It’s always good to verify.

So what the heck does this all mean anyway ? The .45 Super® has the least capacity. An indication of the internal area lost when strength was added to the web area for reinforcement against elevated chamber pressures. Does water weight interpret into powder charge weight ? Each powder has it’s own density, and all are different from water weight. In the case of Alliant Power Pistol, powder weight per volume is about 20% less than water. Power Pistol at a max load will not require compression with the .45 Super brass and 185 grain bullets. AA 7, another slow burning pistol powder looks as though it may.

Okay, gun’s ready, ammo’s loaded and ready, and I will post specific load data and overall gun / cartridge performance in the next installment. By then, with this new heavy duty recoil spring in place, I should be well on my way toward growing a left arm like Popeye’s.

More “A Kimber in .45 Super®1 for under $8?”:

A Kimber in .45 Super® for under $8 ? – Part I

A Kimber in .45 Super® for under $8 ? – Part II

A Kimber in .45 Super® for under $8 ? – Part III

Handload Data 45 Super®1

Thanks,

Joe

Email Notification