Some may look at the photo on the left and see three boxes, 150 bullets in total, of Barnes’ new high performance Triple-Shock Bullets. Other’s may see $71.09 in an alternative form. As a frugal optimist, I tend to see both.

I’m pretty excited about the Triple-Shock product, to the extent I purchased several variations. Based upon the design, I have hopes they will help me achieve a level of ballistic horse power I could not have attained before. What took me to this project…

Bullets with driving bands

Bullets with driving bands have been with us for a very long time. Dating back before the Civil War, cast bullets utilized driving bands to reduce bore leading and hold lubricant and, in some cases, to assist in bullet heal expansion to facilitate bore sealing. As a modern machined solid material bullet, Barnes is not the first company to place driving bands on the shanks of its bullets. As an example, the moly coated bullet on the right is a product of GS Custom Bullets of South Africa, their line has been in production since 1993. I’ve worked with the GS bullet in the past, in conjunction with .257 Weatherby Magnum handloads, and found I could achieve 100 fps edge over bullets of a more traditional configuration, although I am not certain if the improvement came from the driving band, the moly coating or, perhaps, a combination of the both. Unfortunately, at $41.00 and $12.50 shipping for 50 bullets, the 100 fps came at too high of a price. At $19.00 for a box of 50, or 35% of the cost of the GS product, the new Barnes bullet is a comparative value.

Barnes’ Triple-Shock expressed benefits are: significantly increased velocities, lower pressures and less fouling without requiring an external coating. I believe, if bearing surface is reduced in a meaningful way, it is an established fact all three of these benefits will result to some degree. All thing equal; gun, cartridge and bullet, increasing the average pressure behind the bullet, before it leaves the bore, should result in a corresponding increase in velocity. Driving bands on bullet shanks can create this condition by lowering initial resistance, thereby lowering peak pressure for a given powder charge, thereby allowing a slightly heavier powder charge that will generate higher average pressure, while potentially not exceeding peak pressure limits….honest. No, I’m not exactly sure what I just said, but permit me to go on a bit and see if I can have it make more sense to all of us.

Theoretically speaking…

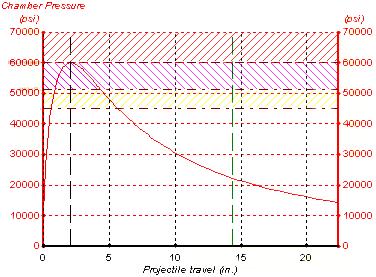

When ignition occurs in a cartridge, there is a resistance to the bullet’s forward progress as it moves forward to the rifling and obturates under pressure. I don’t know why I used the word “obturates”. Sometimes when I write articles with half baked technical information I begin to sound like the King for France, so let’s substitute the word “deforms”. The pressure required to overcome this resistance is generally expressed as initial or shot start pressure. The charts used in illustration were all generated with QuickLoad, then diminished in quality by me when I compressed each file to reduce its size.

A solid composition bullet, in this case copper, with a traditional shank may require 6,500+ PSI to overcome this initial resistance, pressure that will contribute to the 60,000 PSI peak pressure that will occur approximately 2.1″ down the bore. Beyond that point, powder will continue to burn, but the ever increasing space in the bore behind the moving bullet will cause pressure to steadily drop, and reduce the bullet’s rate of acceleration. In the charted example, the average pressure generated by this combination will result in a muzzle velocity of approximately 3,095 fps. Adding powder to increase this velocity is not possible with this bullet and powder combination because while the average pressure might increase, the peak pressure would increase above the 60,000 PSI maximum safe level. Reducing shot start pressure, while increasing average pressure would result in sustained bullet acceleration, and resulting higher velocity – which is the objective of bullets with a reduced coefficient of friction.

A solid composition bullet, in this case copper, with a traditional shank may require 6,500+ PSI to overcome this initial resistance, pressure that will contribute to the 60,000 PSI peak pressure that will occur approximately 2.1″ down the bore. Beyond that point, powder will continue to burn, but the ever increasing space in the bore behind the moving bullet will cause pressure to steadily drop, and reduce the bullet’s rate of acceleration. In the charted example, the average pressure generated by this combination will result in a muzzle velocity of approximately 3,095 fps. Adding powder to increase this velocity is not possible with this bullet and powder combination because while the average pressure might increase, the peak pressure would increase above the 60,000 PSI maximum safe level. Reducing shot start pressure, while increasing average pressure would result in sustained bullet acceleration, and resulting higher velocity – which is the objective of bullets with a reduced coefficient of friction.

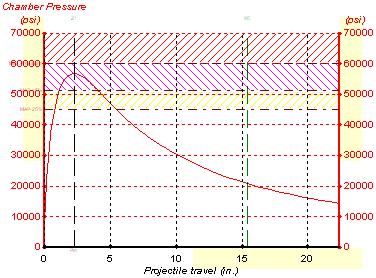

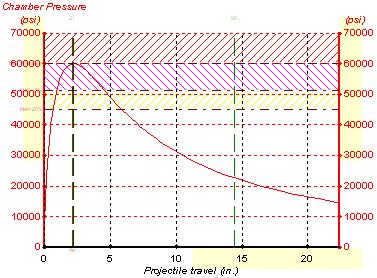

With a reduction in in shot start resistance through reduced bullet bearing surface, in our example, shot start pressure drops to 4.300 PSI, peak drops to 56,800 PSI and muzzle velocity is reduced to 3,067 fps. Because peak pressure was reduced, and no additional propellant was added, average pressure was reduced also. Now operating well below the peak pressure limit of 60,000 PSI, more powder was added to bring the load back closer to the peak limit. What amounts to another grain of powder raises peak pressure to 60,000 PSI, average pressure increases, as does velocity to 3,130 fps.

Running up and down the velocity and caliber scale, through calculations it appears 45~50 fps is a realistic reflection of gains to be had from a single method of resistance reduction. The GS Custom bullet offered 100 fps greater velocity over a more traditional bullet, but it used a combination of reduced bearing surface and moly coating to achieve this result.

Even 45~50 fps is a substantial gain when there is no associated premium price for the boost in velocity performance.

The silent world of customer service and BC

A bullet’s ballistic coefficient indicates to what degree it is streamlined, a key factor in retained velocity and energy. Barnes bullets tend to be a little more slippery than the average same bore and weight projectile, but I wondered what effect those three grooves would have on drag. Beyond overall profile of an object, at very high speeds, almost any surface irregularity will increase drag. So I shot an email off to Barnes and asked for the BC figures for the Triple-Shock line up and received…no response and as of this writing, the Triple-Shock remains the only bullet on the Barnes site without this data. Without BC a shooter can’t plot trajectory, zero at a distance, calculate point blank range, etc. so the missing information isn’t of minor importance.

As an alternative, I took a look at the Lazzeroni site, where they have cleverly disguised the same product by naming it “Lazerhead”, plating it with NP3 and charging twice as much per bullet. They list the same BC as the corresponding plain shank X-Bullet. I don’t believe it is possible that three significant grooves, pushed through the air perpendicular to the direction of flight, would not have a negative effect on drag. However, sometimes boundary layers do strange things when it comes to streamlining, so I will reserve final judgment until I care enough to set up the System 43 for 100 yard BC testing.

Real World Assessment

Three rounds I handload have been taped out in terms of maximum velocity attained with conventional bullets; the 7mm Remington Magnum, the .270 WSM and the .257 Weatherby Magnum. There are only so many combinations to flog and, unless some component’s functional design changes, there is little to gain with further experimentation. I have used Barnes bullets in X and XLC forms with good success, so I thought it might be interesting to see if I could move the velocity marker, so to speak, with the Triple-Shock configuration.

The bullets of interest to me were the 160 grain .284″, 130 grain .277″ and the 115 grain .257″ as I had lots of data from same weight loads with bullets from a good number of competing manufacturers. The 50 piece Triple Shock price was, respectively, $26.39, $25.59 and $19.11. To put these prices in perspective, the plain X-Bullet equivalents are priced at $22.30, $21.70, $22.00*, XLC Barnes equivalents run approximately $28.18, $26.31, $23.00. *Price is from Lock Stock & Barrel, the rest were taken from Midway USA. By comparison, comparable jacketed soft points from Sierra ran $15.45, $13.45, $13.45 as a 100 PIECE PRICE (yes, the .270 and .257 were the same price). So, basically, you would spend $10 for every 20 cartridge box of handloads with Barnes Triple Shock bullets, and $3 per box for Sierra Po Hunter bullets. Oh, I think I just figured out why Barnes doesn’t answer my tech support questions.

While it may not seem obvious, I’m not trying to be a jerk about the price of Barnes bullets. The truth of the matter is, manufacturing processes and shop time and materials vary, so it may even be that Sierra has a higher profit margin on their lower cost bullets than Barnes. The issue for the handloader and hunter becomes one of value; does the Barnes bullet offer sufficient practical benefits to warrant the additional cost? That is a question each individual shooter has to answer for themselves.

I’ve probably been exceptionally lucky, as I have never encountered a bullet that broke up so badly that a game animal walked away after being hit with a well placed shot. I have retrieved bullets that shed their jackets, bullets that broke into a couple of parts and bullets that seemed to do a bit more damage than appreciated to what could have been a nice roast. The only things these bullets had in common was that they were retrieved from dead animals and they were all “cheap” bullets. I still buy lots of Barnes, Nosler, Swift, Woodleigh and Premium Speer bullets, but mostly because I love to experiment with handloads and see how fast and how accurately I can get a rifle and cartridge combination to perform. For these reasons alone, the premium bullets referenced all have value. If I were hunting for something more dangerous than the average field mouse, something very large with claws and teeth, the margin of insurance offered by a premium bullet would also be a value.

A classic apple to tangerine comparison

Laying two .277″ 130 grain Barnes’ bullets down side by side, an XLC and a Triple-Shock, made me wonder how Barnes compensated for metal removed from the three grooves to get to the same weight. In a little closer assessment, the Triple-Shock measured .012″ longer. The shank of the coated XLC measured a dead on .277″. The shank of the Triple Shock was .2765″ and the grooves measured .2615″; .015″ smaller diameter for a groove depth of .0075″. The XLC bullets weighed an average of 130.1 grains, the Triple-Shock 129.6 grains, or half a grain lighter. Perhaps there is a subtle difference in ogive profile that would be picked up with an optical comparator.

Of course, as a new bullet, there is no Triple-Shock handload data readily available. Seems I remember Barnes packed some load data in the XLC bullet boxes when that product was initially released. Within the three types of Triple-Shock I purchased one, the .277″, contained a loading technique slip sheet. The slip sheet info suggested Triple-Shock handloads begin with the minimum loads listed for the corresponding uncoated X Bullet. They go on to suggest the Triple-Shock, if not demonstrating symptoms of excessive pressure (some noted) may be loaded to 0.5~2.0 grains above the X Bullet maximum loads. In no way, and under no circumstances did they intimate using XLC data or suggest that it was safe to begin at any level other than the minimum loads for the X Bullet. There is a huge difference between X Bullet and XLC bullet load data. In the case of a 7mm Remington 160 grain load, as an example, the XFB uncoated bullet lists a max of 63 grains of Re 22, while the XLC FB indicates a maximum load of 72.5 grains of Re 22. Do not use XLC data for Triple-Shock bullets.

What’s next?

I have worked up handloads with the Triple-Shock bullets, and I will be back next week with some quantified performance data. Right now I need to play musical scopes and find the WSM shell holder.

More “Barnes Triple-Shock X Bullets”

Barnes Triple-Shock X Bullets Part 1

Barnes Triple-Shock X Bullets Part II – Conclusion

Thanks

Joe

Email Notification