There is a lot to be said for simple machines that accomplish an objective, including those machines used for: hunting, informal target shooting and consumption of handloads. I get a kick out of hunting articles that run through the process of – “I glassed the slopes with my binoculars and spotted the (insert applicable) in the middle of the herd, then switched to my rangefinder and placed the extraordinary (blank) at 300 yards. My guide went ahead to check out the herd, while I unfolded my lawn chair/shooting bench, assembled the spotting scope, checked my position with my GPS and settled in for what I knew would be a tough shot. The cast iron rifle rest held the 6.5mm Macaroni steady. Not realizing, prior to the hunt, how long of a shot I would be taking, my gun was equipped with only a rudimentary 2-16x scope and laser dot reticle.” My personal hunting experiences have been somewhat different, “I was sitting on a large rock, drinking coffee, when I heard the twig snap behind me. I dropped my thermos, turned and pulled the Marlin to my shoulder, just in time to see the flag of a giant deer’s ass disappearing into the distance. Angry, I attempted to kick a tree, fell off the rock, and rolled down the hill “.

There is a lot to be said for simple machines that accomplish an objective, including those machines used for: hunting, informal target shooting and consumption of handloads. I get a kick out of hunting articles that run through the process of – “I glassed the slopes with my binoculars and spotted the (insert applicable) in the middle of the herd, then switched to my rangefinder and placed the extraordinary (blank) at 300 yards. My guide went ahead to check out the herd, while I unfolded my lawn chair/shooting bench, assembled the spotting scope, checked my position with my GPS and settled in for what I knew would be a tough shot. The cast iron rifle rest held the 6.5mm Macaroni steady. Not realizing, prior to the hunt, how long of a shot I would be taking, my gun was equipped with only a rudimentary 2-16x scope and laser dot reticle.” My personal hunting experiences have been somewhat different, “I was sitting on a large rock, drinking coffee, when I heard the twig snap behind me. I dropped my thermos, turned and pulled the Marlin to my shoulder, just in time to see the flag of a giant deer’s ass disappearing into the distance. Angry, I attempted to kick a tree, fell off the rock, and rolled down the hill “.

Not much has changed for me over the years from a firearms standpoint. I generally hunt on land that goes steeply upward, or downward, with not much level in between. As a result, I will persist in not hauling much with me that isn’t a firearm, cartridges, a knife, or comfortable clothing. Topography and trees will limit shots to under 100 yards or so, and deer / black bear size game will negate the need for magnum cartridges. So when I found myself shopping for what I needed least, a new rifle, I was determined to make it a unique experience and at least find something practical. In the past, I’ve acquainted myself with the facts of the situation, then thoroughly researched and matched the gun specs to the application. However, I would head for the gun store to purchase an ideal duck gun, and come home with a .416 Weatherby. As an alternative to my wife’s suggestion that I might seek professional help I decided, this time, I would make my firearm selection, avoid the gun store, and have my wife make the actual purchase.

The experiment worked, yielding a rifle that: weighs one half pound less than my .270 WSM Super Shadow, holds twice as many cartridges and is half a foot shorter. With a six inch kill zone, the gun provides a 200 yards of point blank range, which is twice the distance I require. Recoil is non-existent and, at $11/box for premium ammo, it is less than half the price of the .270 WSM. In addition the gun has a walnut stock, which I will always prefer, and at a price that won’t cause me to worry about scratches in the finish when it’s getting dragged through the woods. As a bonus, I already handload for this cartridge, so I have lots of components on hand. I can only conclude that I have identified, and obtained, what could only be labeled the perfect practical hills rifle.

The Winchester Model 94 AE .30-30 Vs. Marlin

When I was a youngster and selecting a first center fire rifle, I wanted something that would bring down game. However, being 11 years old, I also thought I might still want to become a cowboy, so the influence of Chuck Conner’s TV show “The Rifleman” was not insignificant. Having very opinionated little friends, who loved guns and knew specs inside and out, a great deal of debate took place and ” Winchester vs. Marlin” became the topic for weeks of discussion. Ultimately, Marlin prevailed, with it’s closed top receiver for ease of scope mounting the deciding factor, along with the potential for greater accuracy based on Marlin’s Micro-Groove rifling. I did get the Marlin but, unlike the Guide Gun model pictured right, my Model 336 Carbine was never fitted for a scope. Fortunately for me, this apparently never got in the way of bringing down deer and other assorted game over the years. Things have changed significantly for Winchester and Marlin, which caused me to make a Winchester decision this time around.

When I was a youngster and selecting a first center fire rifle, I wanted something that would bring down game. However, being 11 years old, I also thought I might still want to become a cowboy, so the influence of Chuck Conner’s TV show “The Rifleman” was not insignificant. Having very opinionated little friends, who loved guns and knew specs inside and out, a great deal of debate took place and ” Winchester vs. Marlin” became the topic for weeks of discussion. Ultimately, Marlin prevailed, with it’s closed top receiver for ease of scope mounting the deciding factor, along with the potential for greater accuracy based on Marlin’s Micro-Groove rifling. I did get the Marlin but, unlike the Guide Gun model pictured right, my Model 336 Carbine was never fitted for a scope. Fortunately for me, this apparently never got in the way of bringing down deer and other assorted game over the years. Things have changed significantly for Winchester and Marlin, which caused me to make a Winchester decision this time around.

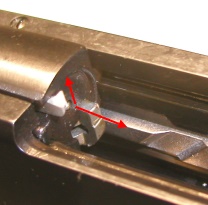

Since approximately 1984, Model 94’s have had angle ejection, so the rifle accepts a traditional above receiver scope mount set up. In the picture to the left, the up arrow is actually straight up and down, the second arrow pointing to the ejection ramp is at about 135 degrees off vertical, which means spent cases eject at about a 45 degree angle from the receiver.

Since approximately 1984, Model 94’s have had angle ejection, so the rifle accepts a traditional above receiver scope mount set up. In the picture to the left, the up arrow is actually straight up and down, the second arrow pointing to the ejection ramp is at about 135 degrees off vertical, which means spent cases eject at about a 45 degree angle from the receiver.

Marlin’s .30-30 WCF models still have Micro-Groove rifling, the Winchester traditional 6 groove, and not unlike the Ballard type rifling used by Marlin for its .45-70 products. The Marlin has a tighter twist rate of 1:10 versus the Winchester’s 1:12. The longest bullet I could identify for the .30-30 is a Barnes 165 grain X FN. At 1.165″ a 1:15 twist is optimal, so the 1:12 Winchester twist is more than enough to ensure bullet stability.

The Winchester has a pull of 13 1/2″, the Marlin 13 1/4″. The Winchester drop at the comb is a full 1 1/8″, 1 7/8″ at the heel, making for more natural metallic sight / eye alignment. The Marlin has a 1 1/2″ drop at the comb and 2 1/4″ at the heal which, as a practical matter, is the same. To the preceding information in context, Winchester Super Shadow Model 70 specs are 13 1/4″, 5/8″ and 7/8″ respectively, less comb drop for more natural eye alignment with a scope mounted an inch or so off the barrel. The 94 has a straight grip, no pistol grip, and neat cut checkering on the grip and forearm. The wood finish has an oil rubbed appearance, darker in color than the finish applied to Marlin rifles. The example I purchased has a cross bolt safety that passes through the side of the receiver. The newest generation for late 2003 relocates the safety to the tang and off the receiver, however, this version was not in distribution at the time of my purchase, and the change wasn’t significant enough for me to wait. You can accuse me of blasphemy, but having a solid bar between the firing pin and hammer is an extra margin of safety I can live with.

It’s sort of comical to read some of the lofty comments made on message boards about the Model 94 with references to a “Proper Model 94” not having a scope, or how the cross bolt safety is an “aesthetic atrocity”. The Model 94 is, as it always has been, not much more than a pile of mild steel wrapped in wood that serves a specific purpose; hunting. A “proper” rifle is one that does what it is intended to do, one that meets the requirements of its owner. Aesthetically “proper rifles” begin with a price tag on the upside of $10,000. Turn up an engraved and gold inlaid Model 94, with a serial number below 10, then I might be willing to listen to this non-shooter chatter about proper Model 94’s.

The Winchester’s sight system in a reliable buckhorn type rear, with hooded bead up front. The rear sight is adjustable for elevation by sliding a stepped ramp under the rear sight. Windage adjustment is accomplished by drifting either the front or rear sight. The Marlin set up, below, is virtually the same. The Winchester Model 94, like the Marlin 336, is tapped for scope mounts. Since the metallic sights on either rifle mostly cover up a deer at 100 yards, the addition of a compact scope that will not detract from the rifle’s compact form can go a long ways toward helping the shooter actually place precise shots.

The Winchester’s sight system in a reliable buckhorn type rear, with hooded bead up front. The rear sight is adjustable for elevation by sliding a stepped ramp under the rear sight. Windage adjustment is accomplished by drifting either the front or rear sight. The Marlin set up, below, is virtually the same. The Winchester Model 94, like the Marlin 336, is tapped for scope mounts. Since the metallic sights on either rifle mostly cover up a deer at 100 yards, the addition of a compact scope that will not detract from the rifle’s compact form can go a long ways toward helping the shooter actually place precise shots.

I’d like to speculate regarding the strength of the Model 94 action, but I have no real facts to support an opinion. Barrel shank diameter (.930″) and related receiver width (1.220″) are almost identical between the Marlin and Winchester. Both are factory rated to withstand .30-30 SAAMI spec, which is 42,000 PSI (38,000 CUP) MAP. I know Winchester did produce a Big Bore version that was chambered for the .375 Winchester with a MAP of 52,000 PSI, however, I do not know what mechanical and process differences existed in this higher pressure model other than thicker receiver walls. Winchester currently chambers the Model 94 only for cartridges with pressure levels similar to the .30-30 WCF. In any event, the .30-30 WCF is not the type of cartridge that responds well to excess powder charges, so the Model 94 will be strong enough for any handloads I will put together. As an observation, where the Marlin rifle bolt cams closed on the nose of the lever and a secondary level hook located about midway down the length of the bolt, the Winchester has a similar front end lever contact, plus a breech block (arrow) at the rear of the closed bolt – a little like a falling block design.

A few more general factoids – At 6 1/4lbs, the Winchester weighs 3/4 of a lb less than the Marlin 336, .30-30 or .45-70. All guns noted share the same hefty trigger pull at 5 1/2 lbs, which feels natural after a time, and seems to have no bearing on shooting accuracy. Both guns can be purchase in the $375~$400 range at these model levels. Both make upscale and downscale versions with pricing commensurate with grade of finish.

Now that I have this spiffy lever gun, I’m going to put together some handloads, see if I can’t come up with a decent scope set up, and see what type of performance I can get out of the this Winchester. It will be nice to work with a rifle, for a change, that does not beat me black and blue, blow out my ear drums or max out my credit card when I purchase handloading components.

More “The Ultimate Woods Rifle”:

The Ultimate Woods Rifle – Part I

The Ultimate Woods Rifle – Part II

The Ultimate Woods Rifle – Part III

Handload Data 30-30 WCF

Thanks,

Joe

Email Notification