In the past, I may have made one or two derogatory comments regarding firearm enthusiasts who own military firearms. Yes, my opinions may have been steeped in ignorance of the subject, but still there was always that visual image of a 20 year old guy, sitting in a tiny apartment, dressed in a WW I military uniform, having a wine and cheese date with a scantily clad mannequin. However, reality set in when I realized I know people who own antiquated military firearms and they don’t even LIKE cheese. I had to consider it was possible some of my other perceptions were incorrect as well. After some cursory investigation through books, message boards (military surplus firearms have some excellent boards) and visits to several places that sell military surplus material, I developed the sense individual’s interest in these old firearms fell into several broad categories: financially motivated collectors, historical collectors and enthusiasts who enjoy firearm related metal and woodworking projects originating with inexpensive military surplus firearms.

I’m not sure how I feel about financially motivated collectors; firearms are frequently taken out of circulation and public view and buying and selling activity drives prices through the roof and away from people who may actually have an interest in firearms. Still, these folks are careful and protective of their inventory, so the conclusion in any event is preservation of firearms and related information. Historical collectors also have the knowledge and resources to preserve firearms, but they typically share information and display firearms. I believe most project oriented people, the last category, are rarely guilty of carving up collectable firearms. They typically buy readily available and inexpensive surplus firearms and end up with a piece that is mechanically better than as purchased and a much better shooter. It is these lower budget efforts and frequent transactions that probably do more to keep this history in public view than either of the other categories.

I’m not sure how I feel about financially motivated collectors; firearms are frequently taken out of circulation and public view and buying and selling activity drives prices through the roof and away from people who may actually have an interest in firearms. Still, these folks are careful and protective of their inventory, so the conclusion in any event is preservation of firearms and related information. Historical collectors also have the knowledge and resources to preserve firearms, but they typically share information and display firearms. I believe most project oriented people, the last category, are rarely guilty of carving up collectable firearms. They typically buy readily available and inexpensive surplus firearms and end up with a piece that is mechanically better than as purchased and a much better shooter. It is these lower budget efforts and frequent transactions that probably do more to keep this history in public view than either of the other categories.

An Educational Process

Working with military firearms is an education through osmosis. In trying to identify a firearm’s origin and history, you’re taken through all of the surrounding world history including a pretty good depiction of friend and foe, nations and allies. In reading about a specific firearm’s capability, durability and longevity, you learn a lot about the nation of origin’s industrial and technological capabilities. You even learn something about the mind set and physical structure of the people who used the weapons and the outside world’s level of respect or lack of respect for all of the above.

Studying various issues or generations of weapons gives a lot of insight into firearm design; knowing why a rear sight design was changed over time, why certain parts fail, what potential these guns and assemblies have to offer, all give great insight into firearm designs and early firearm concept discards. You can’t do that today. Try calling a modern manufacturer’s tech line and ask the pressure capacity of one of their products, or what specific alloys they use, or who is the specific designer, or…..

Most military surplus firearms within the scope of this article are cheap, of mixed origins and of dubious working condition. Only milsurp firearms can lead you to a three day exploration into the world of best methods to leech cosmoline out of vintage walnut, or the pros and cons of Easy Off Oven Cleaner over Simple Green or Greased Lightning as a preliminary cleaner. These ancient relics can lead to rediscovery of 220 grit sandpaper, oil based wood stain and sealer, metal draw files, nuclear bore cleaner, and in search of a bluing shop that won’t laugh hysterically when you tell them you want the modern scratches and flaws removed, but the original marks and combat scars left in place. Unlike most of the shiny stuff I own, these are real guns.

Big 5 Stores – a Great Source

I’m not sure what “Big 5” means. I know it use to mean the big 5 African trophy animals; Lion, Elephant, Rhino, Leopard and Buffalo. Maybe not today, but I like the company’s name association, and the fact that a California based sporting goods retailer uses the word “hunting” on their website and carries firearms throughout their chain of 309 stores in 10 Western states. How could you not shop to support that type of organization? Every week, Big 5 places an ad insert in the Sunday paper filled with sales on golf clubs and lawn chairs, fishing tackle and sneakers and, prominently displayed, sale prices for various military surplus rifles. Usually there is a weekly rotation through varieties of Mausers, Enfields and Mosin Nagants. They also carry ’03’s, ’17’s and other, although maybe not sale items, still very low in cost, but probably not something to tinker with out of respect for history and limited availability.

The sections of rifle appearing in pictures throughout this article was purchased for $75 as a “Rifle, Turkish 1938 Cal 8mm”. That’s shorthand for a Mauser of various and unidentified origins, cobbled and remarked in a Turkish armory to reflect some unspecified Turkish standard, then dunked in a vat of Cosmoline for approximately 65 years until purchased by Century International Arms….then hosed down, free hand marked with engraving pen graffiti, dunked in Cosmoline again and then sold to Big 5. Which is what the very helpful and cautioning sales person kept trying to tell me when I insisted on buying a less than stellar example.

The sections of rifle appearing in pictures throughout this article was purchased for $75 as a “Rifle, Turkish 1938 Cal 8mm”. That’s shorthand for a Mauser of various and unidentified origins, cobbled and remarked in a Turkish armory to reflect some unspecified Turkish standard, then dunked in a vat of Cosmoline for approximately 65 years until purchased by Century International Arms….then hosed down, free hand marked with engraving pen graffiti, dunked in Cosmoline again and then sold to Big 5. Which is what the very helpful and cautioning sales person kept trying to tell me when I insisted on buying a less than stellar example.

I wanted a project rifle, not a near pristine, refinished or refurbished rifle, even though Big 5 had guns that were very clean and correspondingly graded. The gun I purchased was graded “Good”, and all of their rifles have been inspected and are in shooting condition; the worst of the lot still isn’t too shabby and this is a nice safeguard service Big 5 provides. Visit any message board populated with C&R (Curio & Relic) FFL participants and you will read horror stories about purchasing rifles from online distributors and discovering everything from severe bore corrosion to marine worm infestation.

The store staff pulled out rifles from the back room that had yet to be prepped for display, the store manager and assistant manager were gun people and answered questions carefully, thoroughly and with patience, and they had a good inventory of rifles. I did go to several area Big 5 operations while I was shopping for a specific type of gun. They were all good with the exception for the Sunnyvale, CA store on Steven’s Creek, which seemed not to have anyone willing to wait on customers at the gun counter, or any other counter. The best store and staff of the bunch was –

Big 5 Sporting Goods #123

757 E. Calaveras Blvd.

Milpitas, CA 95035

(408) 262-1726

Customers are greeted coming in the door with a smile, sales people venture out onto the floor to offer help and the gun counter has knowledgeable people who can just as easily provide insight into fishing tackle or a hunting knife as firearms. The store manager, a very helpful guy, is Elgin Sanchez. Over the course of a week I actually purchased three guns of a similar type, the guns were delivered complete and with related accessories; bayonet, sling, ammo belts, oiler, etc. I bought a Turkish Mauser that was a little rough around the edges and two excellent condition Mosin Nagants that looked almost as good as new Winchester production. My wife was no help in getting me out of the store. If we had stayed much longer she would have talked me into one of those Swiss things with the ring on the end of the bolt; we share a mutual interest in firearms. Over some period of time I’m going to modernize, not sporterize, and rebuild the Mauser into a solid shooter and spend some time handloading for the 8x57mm Mauser. The Nagants will remain intact and will be used mostly for developing 7.62x54R Russian handloads and pondering why they built a rifle that can only mount a scope like a rear view mirror. I will make sure I document every dufus error I make and embarrass myself publicly with disclosure, hopefully sparing someone else the aggravation.

What’s rounder, an orange? A little convoluted history…

I got the Mauser home and took a bunch of traditional “before” pictures for a number of reasons. When the project is completed I can brag about how comparatively good the gun looks, or explain away why the project didn’t end so successfully, or the real reason – so I would know where all the parts are suppose to go when reassembled. I also wanted to be able to post images around the Internet to see if someone could tell me what the heck the gun was besides a Turkish Frankenstein. I know that would seem an easy task, but it isn’t really. Some Turkish Mausers were made under specific contract, some were made in Turkish facilities and some were conversions from any number of Mausers models used to fulfill contracts with a best model available clause. This could include models 1890, 1893, 1903, 1905 carbine, G 98 and the Czech 98/22.

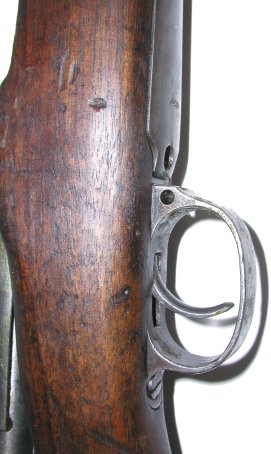

![]() My gun is similar to a 1903 Turkish Mauser, but with a large ring action and 1.1″diameter barrel thread and a 4 screw trigger guard which is consistent with a GEW 98. “GEW” is short for Gewehr 98, or “Rifle 98”, the basic German infantry firearm . The exceptions to early GEW 98 configuration are the absence of a Lange type rear site, which is consistent with the gun being chambered for the flatter shooting 7.9mm (8mm) Mauser, and a bayonet lug in place of a parade hook on the upper band which is more consistent with a 1903 Turkish Mauser part. More than likely, the gun began life as a GEW 98, then was reworked at the Askari Fabrika Turkish military factory to a common standard, including the rebarrel to 8mm Mauser and the corresponding tangent rear sight . The stock is walnut and devoid of grasping grooves, indicative of pre 1915 GEW production. The rifle has been restamped 1938 on the receiver ring, consistent with a German firearm reworked for Turkish service. If you see a Turkish Mauser advertised, chances are it could have been accurately labeled, “Assorted Mauser parts reworked and assembled in Turkey”. This is not a statement of substandard quality, only information regarding origins. Outside of reworked models listed in the preceding paragraph, some complete Mausers were produced in Turkey. Typically marked “K.KALE”, Kirikkale Tufek Fabrikast , the Kirikkale Rifle Factory, these have full length, large ring proportioned actions with a small ring Mauser barrel thread diameter.

My gun is similar to a 1903 Turkish Mauser, but with a large ring action and 1.1″diameter barrel thread and a 4 screw trigger guard which is consistent with a GEW 98. “GEW” is short for Gewehr 98, or “Rifle 98”, the basic German infantry firearm . The exceptions to early GEW 98 configuration are the absence of a Lange type rear site, which is consistent with the gun being chambered for the flatter shooting 7.9mm (8mm) Mauser, and a bayonet lug in place of a parade hook on the upper band which is more consistent with a 1903 Turkish Mauser part. More than likely, the gun began life as a GEW 98, then was reworked at the Askari Fabrika Turkish military factory to a common standard, including the rebarrel to 8mm Mauser and the corresponding tangent rear sight . The stock is walnut and devoid of grasping grooves, indicative of pre 1915 GEW production. The rifle has been restamped 1938 on the receiver ring, consistent with a German firearm reworked for Turkish service. If you see a Turkish Mauser advertised, chances are it could have been accurately labeled, “Assorted Mauser parts reworked and assembled in Turkey”. This is not a statement of substandard quality, only information regarding origins. Outside of reworked models listed in the preceding paragraph, some complete Mausers were produced in Turkey. Typically marked “K.KALE”, Kirikkale Tufek Fabrikast , the Kirikkale Rifle Factory, these have full length, large ring proportioned actions with a small ring Mauser barrel thread diameter.

The stock looked pretty good, a little like the floor in an old machine shop that hadn’t been cleaned in a 100 years or so. The hole in the butt stock is a disassembly tool that aids in disassembly and assembly of spring loaded bolt parts. Somewhere around mid WW1, this replaced a marking disk that identified the gun’s unit of assignment. An alternative, but unsubstantiated, explanation for this piece of hardware is that the through hole was used to locate a locking rod during shipment.

I still don’t have a lot of precise information about my rifle, but I did learn enough to convince me I wasn’t in the possession of a Mauser owned by Elvis. Accordingly, my gun was not received “replete with valuable patina of antiquity” in the vernacular of Antique Roadshow, it was just filthy and in need of a clean up. I could now, without an attack of collector’s conscience, sand, refinish, reblue and even making improvements, or what others may refer to as senseless modifications. That said, I still do not want a Mauser that looks new, nor do I want a weird looking Mauser. I want something that looks like a military firearm of some age, but one that shoots well, looks good and is relatively easy to maintain. What does that mean? We’ll, I would not replace the stock with new wood and lose the dings and knocks that marked the history of the gun. However, I would have no problem bluing the receiver and other parts that in some models was originally left in the white.

Basically sound, older than me, but in better shape…

A good place to check a rifle’s state of health is headspace. Before disassembling the entire rifle, I pulled the bolt and removed the extractor in preparation for checking headspace. Unfortunately, the go no-go gage set from Brownells is cut to the modern 8x57mm SAAMI spec with a 19° shoulder angle, rather than the 8x57mm JS original 20° 48’ standard. Gages to the old standard can be ordered through Forster. MidwayUSA carries Forster, Wheeler and PTG but, like Brownells, all are for the SAAMI 8x57mm Mauser standard. With the proper gage, the bolt should close snugly on a go gage, and not close over a no-go gage. With the wrong gage, even a correctly head spaced gun may not close over a go gage. This situation is pretty well documented on the Forster web site as a gage notation and if you run RCBS.Load the 8x57mm JS drawing reflects the older standard. Beyond go and no-go is a field gage. If you live in denial with a gun that closes on a no-go gage, if it will close over this one, you don’t want to shoot it around loved ones. What followed was of course a teardown and thorough clean, followed by a detailed inspection. I wanted to check for cracks, corrosion, erosion, pitting, bent parts, a bulged barrel, bad bore, anything weird that would tell me I wasted time buying loading dies and sandpaper. It wasn’t easy going.

A good place to check a rifle’s state of health is headspace. Before disassembling the entire rifle, I pulled the bolt and removed the extractor in preparation for checking headspace. Unfortunately, the go no-go gage set from Brownells is cut to the modern 8x57mm SAAMI spec with a 19° shoulder angle, rather than the 8x57mm JS original 20° 48’ standard. Gages to the old standard can be ordered through Forster. MidwayUSA carries Forster, Wheeler and PTG but, like Brownells, all are for the SAAMI 8x57mm Mauser standard. With the proper gage, the bolt should close snugly on a go gage, and not close over a no-go gage. With the wrong gage, even a correctly head spaced gun may not close over a go gage. This situation is pretty well documented on the Forster web site as a gage notation and if you run RCBS.Load the 8x57mm JS drawing reflects the older standard. Beyond go and no-go is a field gage. If you live in denial with a gun that closes on a no-go gage, if it will close over this one, you don’t want to shoot it around loved ones. What followed was of course a teardown and thorough clean, followed by a detailed inspection. I wanted to check for cracks, corrosion, erosion, pitting, bent parts, a bulged barrel, bad bore, anything weird that would tell me I wasted time buying loading dies and sandpaper. It wasn’t easy going.

I don’t know how old the Cosmoline was; Turkish install or Century International Arms, but it was nasty. Removal of the gunk allowed me to put on the magnifying lenses and examine the stressed parts for hairline cracks, hack work and wear, but also to uncover some very small and faint ,marks to further identify specifics about the gun. Outside of the bore and chamber, honestly, this is not a place for petrol based solvents unless you like blurry vision and white buffalo hallucinations.

I used two cleaners on external metal and wood parts. The first Greased Lightning is an alkaline based detergent that cuts right through Cosmoline and grit on steel parts. It is not for use on plastic or alloys….or on hands. Wear gloves. The second cleaner I used was Krud Kutter which is a biodegradable detergent and will not eat your hands. After scrubbing I flushed both with hot water and coated with water rejecting preservative oil. Not only were there no cracks forming at corners and wear surfaces, but there was no pitting, rust or other forms of corrosion. The gun was in remarkably good shape, which was a big relief, so I put the metal parts aside until I could decide how, or if, they would be refinished.

I should note that during the course of this work I had several reference manuals to protect me from destroying assemblies in the process. “The Mauser Bolt Actions” by Jerry Kuhnhausen and “Mauser Military Rifles of the World” by Robert W. D. Ball, and some reference from the NRA “Firearms Assembly – Rifles and Shotguns” book. When I got stuck in an area that wasn’t covered, Clark Magnuson was very generous with his time and explanations. In fact, it was Clark’s work with these firearms, along with a Real Gun 1917 Enfield article written by Michael T. Konczal, that motivated me to take a run at this. Other good sources of information and helpful people;www.milsurpshooters.net, www.surplusrifle.com, www.gunboards.com. I’m sure there are many more, but these were the most helpful when gathering information for the project.

Wood Parts

The stock is walnut. I didn’t want to sand too heavily to remove the oil finish and minor dents and scratches out of concern the hardware would fall off when reassembled. I used the same cleaners noted above and a Scotch-Brite pad to cut through the stock crud. After each clean I would hand the stock, fan dry it, then clean it again. I did not want to remove all of the oil from the stock as I was going back to an oil finish and I wanted to maintain a bit of the aged look. In addition to clean up, I used an iron on the wet stock, through a wet cloth, to steam out dents.

I pulled the bolt disassembly tool disks from the stock. I’ve seen suggestions of leaving them in place as the parts are swaged together, sandwiching the stock, but I didn’t think this would be a big deal to put back together or fabricate a new tube. I cut the formed flange with a countersink to remove the parts and came up with an inexpensive tool and easy method to reinstall. Pictured right – This is before and after (top) with only Krud Kutter and the Scotch-Brite pad; not a bad looking piece of old walnut and the wood is unstained or damaged by cleaning. I’ve seen Easy Off Oven Cleaner recommended for oil stripping, placing the stock in a dishwasher (must be a big one), using some really harsh chemicals, wood strippers and a variety of wood cleaning acids. My personal conclusion was these are all destructive to wood cells and are topical cleaning methods. If removing essentially all oil from the stock is the objective, it needs to be drawn out into an absorbent substance. Brownells offers Whiting powder that is mixed into a paste with methanol, TCE, acetone, or toluene then left in place to harden and draw out oil form the wood.

I mixed up my own concoction, just to see if there was a way to duplicate the process with household material. Baking soda is very absorbent, so I tried mixing it with Acetone and painting it on a section of the stock. The Acetone evaporated off too quickly and the baking soda wouldn’t adhere to the wood. Next I tried spraying the wood with Krud Kutter and sprinkling on baking soda. This actually worked. That tan area is oil soaked up from the forearm by the baking soda. The best result I got from baking soda was dipping a hunk of cheesecloth into a tray of Krud Kutter, then wrapping it tightly around the stock, sprinkling backing soda on each layer. Overnight is soaked up enough oil to turn the baking soda uniformly brown.

I mixed up my own concoction, just to see if there was a way to duplicate the process with household material. Baking soda is very absorbent, so I tried mixing it with Acetone and painting it on a section of the stock. The Acetone evaporated off too quickly and the baking soda wouldn’t adhere to the wood. Next I tried spraying the wood with Krud Kutter and sprinkling on baking soda. This actually worked. That tan area is oil soaked up from the forearm by the baking soda. The best result I got from baking soda was dipping a hunk of cheesecloth into a tray of Krud Kutter, then wrapping it tightly around the stock, sprinkling backing soda on each layer. Overnight is soaked up enough oil to turn the baking soda uniformly brown.

So where the heck am I in this process?

The metal parts were stripped disassembled down to the bitty springs and sent out for refinishing. I will cover that area separately when I have the parts back in my hands and I can make an assessment of a new service I am trying. I am finishing off the wood parts and need to make a decision soon as to which I will use. I am leaning toward a boiled linseed oil finish as being closest to original and not as critical to apply as Tung Oil, however, I have both. I also need to decide if I will use a sanding sealer and a stain to further darken the wood. I may wait for the metal parts to come back before making a decision. In the mean time I will work on some handloads, probably at modern 8x57mm pressures, and investigate the rest of these marks to see if I can uncover anymore of this particular gun’s story. This may not be as fancy as covering the 335 Winchester, but it certainly is a lot more fun and a lot more rewarding.

The metal parts were stripped disassembled down to the bitty springs and sent out for refinishing. I will cover that area separately when I have the parts back in my hands and I can make an assessment of a new service I am trying. I am finishing off the wood parts and need to make a decision soon as to which I will use. I am leaning toward a boiled linseed oil finish as being closest to original and not as critical to apply as Tung Oil, however, I have both. I also need to decide if I will use a sanding sealer and a stain to further darken the wood. I may wait for the metal parts to come back before making a decision. In the mean time I will work on some handloads, probably at modern 8x57mm pressures, and investigate the rest of these marks to see if I can uncover anymore of this particular gun’s story. This may not be as fancy as covering the 335 Winchester, but it certainly is a lot more fun and a lot more rewarding.

More “Turkish Mausers and the Big 5 Way Back Machine Part I”:

Turkish Mausers and the Big 5 Way Back Machine Part I

Turkish Mausers and the Big 5 Way Back Machine Part II – Conclusion

Handload data 8x57mm JS

Thanks,

Joe

Email Notification