I wanted to provide some updated information on loads for the .338-378 Weatherby, now that I’ve had a chance to work with Hodgdon H870.

I wanted to provide some updated information on loads for the .338-378 Weatherby, now that I’ve had a chance to work with Hodgdon H870.

123.0 grains H870

250 grain Sierra spitzer soft point boattail

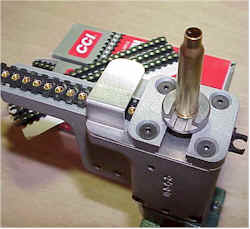

CCI #250 large rifle magnum primers

Avg. MV 3,210

Avg. group size 3 shots well under .700″

Temp was about 52°F and there were no signs of excessive pressure, however recoil was…well…Weatherby like. I’m looking forward to getting some of these other projects off my desk to I can get back to spending more time with this cartridge/rifle combination. I have some Nosler Ballistic Tip 200 grain bullets that should hit orbit entry speed.

And yet one more way to measure rifling twist

Periodically I need to check out rifling twist rate on a firearm I’m working with. As an example, for the past few weeks it’s been verifying twist in Contender barrels prior to selecting bullets for test loads. I’m one of those people who try to use the tight patch on a cleaning rod methods, but it never works for me. Every few inches of travel the patch skids and I end up with twist rates of 1:36. So, with some free time on my hands and an ample supply of scrap and junk, I worked up my own widget.

I start by drilling a small hole above the slot on a cleaning rod patch tip. A .22 caliber rod will work fine for all bore sizes up to around .30. The hole needs to be drilled to about .070″, or twice the diameter of a standard paper clip.

I start by drilling a small hole above the slot on a cleaning rod patch tip. A .22 caliber rod will work fine for all bore sizes up to around .30. The hole needs to be drilled to about .070″, or twice the diameter of a standard paper clip.

A pair of needle nose pliers can be used to clip a loop from a paper clip, and form it into a “Y” shape as illustrated. The narrow portion of the formed piece should be just wide enough to clear the thickness of the flat area of the cleaning rod.

A pair of needle nose pliers can be used to clip a loop from a paper clip, and form it into a “Y” shape as illustrated. The narrow portion of the formed piece should be just wide enough to clear the thickness of the flat area of the cleaning rod.

Clips can be dipped in plastic coating to insure the clips won’t scratch the bore when being pulled through during checking. Probably need to let them dry a little longer than between pictures if you don’t want the plastic to come off on the first pull.

A 14″ .30/30 barrel for the Contender actually has about 11.5″ of rifled bore and it’s important that the clip is in contact with rifling when the measuring process begins. So I measure 10″ up from the tip of the rod and place a single wrap of masking tape. Then I measure 5″ up and put another piece of tape. The spread of 5″ should be the distance between the bottom of the first piece of tape to the bottom of the second piece of tape.

The rod is fed through the breech end of the barrel, until it clears the muzzle, then the rod end is attached. The rod is then pulled through until the bottom of the first piece of tape is just level with the end of the barrel.

The rod is fed through the breech end of the barrel, until it clears the muzzle, then the rod end is attached. The rod is then pulled through until the bottom of the first piece of tape is just level with the end of the barrel.

A small horizontal line is then marked on the tape. This will serve as a reference point, or index mark, so the degree of rod rotation can be observed when the rod is withdrawn from the bore. While a single mark will work, making a mark each 90° will improve accuracy.

A small horizontal line is then marked on the tape. This will serve as a reference point, or index mark, so the degree of rod rotation can be observed when the rod is withdrawn from the bore. While a single mark will work, making a mark each 90° will improve accuracy.

The rod is withdraw to the bottom of the second piece of tape, noting the number of turns, or partial turns, the rod makes through this span of 5 inches.

The rod is withdraw to the bottom of the second piece of tape, noting the number of turns, or partial turns, the rod makes through this span of 5 inches.

Then the number of turns/partial turns is divided into the number 1, and 5 is multiplied by that result. As an example, a half turn would divide into 1, 2 times. 2 X 5 = 10. The barrel has a twist of 1:10, or one full twist every ten inches.

If you are working with a longer barrel, there is nothing that prohibits the tape marks from being spaced 20″, or more, a part. What does remain constant is the number of turns the rod makes during the travel between the marks, divided into 1, multiplied by the number of inches separating the tape marks.

Contender Part III

The Contender, with a Super 14 .223 Remington barrel, had been cleaned up and fitted with Leupold one piece mounts, and a Burris 2X-7X long eye relief scope.

The Contender, with a Super 14 .223 Remington barrel, had been cleaned up and fitted with Leupold one piece mounts, and a Burris 2X-7X long eye relief scope.

At an aim steadying, felt recoil reducing 4 pounds, the gun made me think a bipod, tripod, rest or a hernia would be in my very near future. The gun actually feels good, just nose heavy enough to steady sights. The trigger pull is as it came from the factory, breaking at 3 1/4 pounds. The only item left on the check list, prior to firing, was to bore sight the new scope installation.

Bore sighting the Contender

I didn’t have a .224 arbor for my somewhat mature (that means old, beat up, tired, nobody carries parts anymore…) Bushnell Pocket Bore sighter, so I picked up a reasonably priced Simmons Bore sighter from Brownells. This model covers a range from .17″ – .50″ in 15 increments.

I didn’t have a .224 arbor for my somewhat mature (that means old, beat up, tired, nobody carries parts anymore…) Bushnell Pocket Bore sighter, so I picked up a reasonably priced Simmons Bore sighter from Brownells. This model covers a range from .17″ – .50″ in 15 increments.

The Simmons unit is well made and is easy to use, but I think I would have preferred adjustable arbors to the fixed sized bore spuds, or at least spuds finished with anything softer than hard chrome. Brownells does sell adjustable arbors from B-Square, in three ranges covering .240 – .45, but the range excludes common bore sizes at the upper and lower end, and each of the three arbors cost $20.

If you haven’t used a bore sighter to finalize a scope installation, I could only describe the process as a snap. A spud is affixed to the bore sighter, and the assembly is inserted into the bore of the firearm. Looking through the gun’s scope, the reticle appears overlaid on the grid pattern of the bore sighter. You then crank away on the normal windage and elevation adjustments on the scope and/or scope mount, until the reticle of the scope appears centered and square to the grid in the bore sighter.

If you haven’t used a bore sighter to finalize a scope installation, I could only describe the process as a snap. A spud is affixed to the bore sighter, and the assembly is inserted into the bore of the firearm. Looking through the gun’s scope, the reticle appears overlaid on the grid pattern of the bore sighter. You then crank away on the normal windage and elevation adjustments on the scope and/or scope mount, until the reticle of the scope appears centered and square to the grid in the bore sighter.

There are many elements that determine a bullet’s point of impact, from the way the gun is held to the weight of a bullet. No bore sighter can get you to a bullseye without doing final scope adjustments at the range, but it can get you within a few inches of intended point of impact. It can also save the time and expense of using up boxes of ammo trying to get a shot to hit anywhere on the visible target area. I carry the Simmons with me in my shooting box, and it came in handy when a scope shot loose, and when I wanted to move a scope to a different gun. Works great.

Component and load selection

Every once in a while, I let everyone know I just discovered the earth isn’t flat. Writing about handloads for the .223, rather than the .300 Remington Ultra Mag, may be one of those times. However, the .223 represents a new hands on experience for me, and the .223 is a popular Contender barrel selection. So for those who wish to remain seated….

Buying new brass removes the need to accumulate a lot of empties from live fire, and insures the brass has a known history. Sometimes, “once fired” empties turn out to be sweepings from a range floor, or are the remains of a cartridge that had been loaded and fired with corrosive components. You can purchase new brass from the manufacturer of choice and, when purchased in bulk, it’s available at a pretty good price.

Brass can be ordered with, or without primers. For the purpose of this article, because I knew I would be using various types of primers, I bought unprimed material. Remington .223 virgin brass, through most outlets, routinely sells at a price between 12 – 14 cents. The price is volume based and discount outlets, both on and off the Internet, frequently have sales.

Brass can be ordered with, or without primers. For the purpose of this article, because I knew I would be using various types of primers, I bought unprimed material. Remington .223 virgin brass, through most outlets, routinely sells at a price between 12 – 14 cents. The price is volume based and discount outlets, both on and off the Internet, frequently have sales.

That unit price may seems a little steep, but if each case is reloaded 10 times, the per cartridge cost drops to 1.2 to 1.4 cents. Exactly how many times cases can be reloaded depends upon a lot of factors. Maximum loads with heavy bullets, chambers with excessive headspace, and excessive full length or small base resizing can all contribute to accelerated wear and tear. For less than extreme conditions, I think 20 reloads is a realistic expectation.

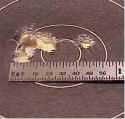

New brass is not perfect brass, and new brass will not save many steps in case prep. From his picture, hopefully, you can see how out of shape some of the material can be when received in bulk form. Most of the imperfections will be disfigured case mouths, small dings, discoloration, and burrs around the mouth edges. Inside/outside chamfering and a quick run through a resizing die will usually most minor neck damage. First firing has a tendency to iron out any minor dings.

New brass is not perfect brass, and new brass will not save many steps in case prep. From his picture, hopefully, you can see how out of shape some of the material can be when received in bulk form. Most of the imperfections will be disfigured case mouths, small dings, discoloration, and burrs around the mouth edges. Inside/outside chamfering and a quick run through a resizing die will usually most minor neck damage. First firing has a tendency to iron out any minor dings.

Case necks may have a pink cast. This is typically the result of the annealing process all brass is subjected to during manufacturing. Annealing is a tempering process that makes the brass pliable prior to forming. Even used brass, that has been heavily sized or reloaded many times, may become work hardened and prone to cracking. Cases can sometimes be annealed by the reloader to make the brass malleable again, and extend its use.

I bought the brass used in this article from Graf & Sons (Order line 800-531-2666). No sales tax for an additional savings of 8.2%, and they pay lower 48 state surface delivery, and the items shipped next day from stock.

I bought the brass used in this article from Graf & Sons (Order line 800-531-2666). No sales tax for an additional savings of 8.2%, and they pay lower 48 state surface delivery, and the items shipped next day from stock.

Remington brand bulk brass seems to have very good quality. On initial measurement, all casings fell within a couple of thousandths of 1.750″ overall length and I don’t think that changed by .001″ after being run through the RCBS full length sizing die.

After working with all large magnum rifle cases the past few months, it was nice to be able to fit 100, rather than 10 rounds or so, in a small plastic reloading bin. Material handling, and the amount of effort required to work a press, makes a big difference when when running off a bunch of handloads. Even metering powder into small capacity case is a comparative pleasure.

There is a ton of reloading data for the .223, unfortunately, some of it is inconsistent. I noticed that even amongst mainstream reloading manuals, there are wide performance differences with same, or very similar loads, +/- a couple of hundred feet per second.

There is a ton of reloading data for the .223, unfortunately, some of it is inconsistent. I noticed that even amongst mainstream reloading manuals, there are wide performance differences with same, or very similar loads, +/- a couple of hundred feet per second.

So I selected what appeared to be optimal from all, noted that primer selection seemed critical with full case and compressed loads, and went with the following –

| IMR 4198 | Primer | IMR 4895 | Primer | AA 2520 | Primer | Win 748 | Primer |

| 21.7 | CCI #450 | 26.5 | CCI BR-4 | 28.0 | CCI #450 | 28.0 | CCI #450 |

| 21.9 | CCI #450 | 26.7 | CCI BR-4 | 28.2 | CCI #450 | 28.2 | CCI #450 |

| – | – | – | 28.4 | CCI #450 |

The bullets selected were: Speer 50gr HP TNT, Nosler 50gr Ballistic Silver Tip and Hornady 50gr SXSP – are all designed to operate in the 1,800 – 3,400 fps range. Based on a ballistic coefficient of .214, and an anticipated muzzle velocity of 3,000 fps, the Contender .223 would be within this bullet design velocity range from muzzle to 300 yards.

The bullets selected were: Speer 50gr HP TNT, Nosler 50gr Ballistic Silver Tip and Hornady 50gr SXSP – are all designed to operate in the 1,800 – 3,400 fps range. Based on a ballistic coefficient of .214, and an anticipated muzzle velocity of 3,000 fps, the Contender .223 would be within this bullet design velocity range from muzzle to 300 yards.

With a variety of powder, bullet and primer selections – all to be assembled in short runs, I set up the Ammo Master as a single station press and used the RCBS bench mount APS press to install primers.

With a variety of powder, bullet and primer selections – all to be assembled in short runs, I set up the Ammo Master as a single station press and used the RCBS bench mount APS press to install primers.

The APS press has meant, no more high primers, and no more primer flipping or chasing rolling primers across the floor. The strips can be snapped together for long priming runs, or easily removed from the press when the job ends in the middle of a single strip. Strips can be returned to the original packaging, safe from contaminants.

A portion of the test rounds were assembled with bench rest primers. All bench rest primers are marked with a small “B” on the impact surface. Dumped into a box with small rifle magnum primers, they are easily distinguishable.

A portion of the test rounds were assembled with bench rest primers. All bench rest primers are marked with a small “B” on the impact surface. Dumped into a box with small rifle magnum primers, they are easily distinguishable.

Bench rest primers have no greater ignition than standard primers, but are manufactured to a closer tolerance. They can not be substituted for magnum primers, but they can be used as an upgrade to standard primers. Magnum / non-magnum primer usage may have a direct impact on chamber pressure. Magnum primers, with greater ignition power, should only be used when specified, and may not be used as a substitute for standard primers. The table below is a comparative reference for various primer manufacturers.

| Mfg. | Small Pistol | Small Pistol Magnum | Large Pistol | Large Pistol Magnum | Small Rifle | Small Rifle BR | Small Rifle Magnum | Large Rifle | Large Rifle BR | Large Rifle Magnum |

| Federal (M) | 100 | 200 | 150 | 155 | 200 | 205 | 210 | 215 | ||

| Remington | 1 1/2 | 5 1/2 | 2 1/2 | 6 1/2 | 7 1/2 | 9 1/2 | 9 1/2M | |||

| Winchester | WSP | WSPM | WLP | WSR | WLR | WLRM | ||||

| CCI | 500 | 550 | 300 | 350 | 400 | BR4 | 450 | 200 | BR2 | 250 |

| RWS | 4031 | 4047 | 5337 | 4033 | 5341 | 5333 | ||||

| M=All are available in match (BR) version, same number designation + a letter “M” |

||||||||||

Rifle data, in most publications, establish cartridge overall length for 50 grain bullets in the .223 as 2.200″. Contender loads, with an assumption of greater freebore, were listed with a 2.260 COL. To hold this cartridge length I had to adjust the seating plug for each of the different bullets, with the shortest bullet requiring the plug to be back out the farthest – inverse of what would be expected.

Rifle data, in most publications, establish cartridge overall length for 50 grain bullets in the .223 as 2.200″. Contender loads, with an assumption of greater freebore, were listed with a 2.260 COL. To hold this cartridge length I had to adjust the seating plug for each of the different bullets, with the shortest bullet requiring the plug to be back out the farthest – inverse of what would be expected.

The profile of the bullet and the profile of the seating plug combine to have more of an effect on seating depth than just the depth of the plug in the seating die. If I spend much more time with this combination cartridge and pistol, I’ll make up a gauge and arrive at a better determination of freebore and optimal cartridge overall length for each bullet.

Powder Selection

IMR 4895, a general purpose cylindrical powder used across a wide variety of cartridges from the .17 Remington to the .458 Winchester. I was actually pretty surprised it would be recommended in such a small case, especially when used in a pistol length barrel.

IMR 4895, a general purpose cylindrical powder used across a wide variety of cartridges from the .17 Remington to the .458 Winchester. I was actually pretty surprised it would be recommended in such a small case, especially when used in a pistol length barrel.

Compared to other smokeless powder burn rates, on a scale of 1 – 10, with 10 being slowest, IMR 4895 is about a 6.5. The charges filled the case up into the neck and required some slight level of compression when the bullets were seated.

IMR 4198 is a stick powder, the granules are longer and thinner than 4895, which contributes to a change in burn rate. It’s faster than 4895, falling around a 5 on the 10 point scale, and a full charge only fills to the case shoulder.

IMR 4198 is a stick powder, the granules are longer and thinner than 4895, which contributes to a change in burn rate. It’s faster than 4895, falling around a 5 on the 10 point scale, and a full charge only fills to the case shoulder.

Like 4895, these are relatively old powders, some of a type dating back to when the US government was starting to issue rifles chambered for the .30/06. Subtle difference, but because charge sizes are 20% less than 4895, 4198 also 20% less expensive per round.

AA 2520 is a 7.5 on a slow burn scale of 1 – 10, it is also a ball or spherical powder. While the charges are heavy, compared to the previous powders, the small granules bring the powder level just above the shoulder, into the neck.

AA 2520 is a 7.5 on a slow burn scale of 1 – 10, it is also a ball or spherical powder. While the charges are heavy, compared to the previous powders, the small granules bring the powder level just above the shoulder, into the neck.

The folks at Accurate are very helpful. They answer E-mail quickly and are and are very helpful in providing lots of data on the use of their products. I’ve found Alliant to be the same. Maybe it’s something about powder companies that begin with the letter “A”.

Winchester 748 is a ball powder designed for medium capacity cases ranging from the .223 to the .308.On the burn scale it ranks about a 6. The powder dispensed uniformly however, because of its bulk, I needed to use a drop tube to fill cases with anything over 28 grains.

Winchester 748 is a ball powder designed for medium capacity cases ranging from the .223 to the .308.On the burn scale it ranks about a 6. The powder dispensed uniformly however, because of its bulk, I needed to use a drop tube to fill cases with anything over 28 grains.

748 seems to show up in more applications than any of the others I selected. I was looking forward to seeing how performance stacked up to published data, as there is the potential of using this is several other moderate capacity cases I’m working with.

Cartridge assembly notes

Bullet runout ran as high as .004″. Maybe I expected a little better concentricity out of a small caliber cartridge. The longer Nosler bullets seem to run a little tighter in alignment, averaging less than .003″. The consistently higher runout came from the Speer TNT bullets.

Bullet runout ran as high as .004″. Maybe I expected a little better concentricity out of a small caliber cartridge. The longer Nosler bullets seem to run a little tighter in alignment, averaging less than .003″. The consistently higher runout came from the Speer TNT bullets.

The Speer bullet seemed to take a different design approach than the other two manufacturers. There was the hollow tip, that I understand is to react to fluid pressure for rapid expansion, but there were also striations in the jacket to apparently help expansion along.

Bullet weight variations were about the same in all three products. The Speer had the highest swing from -.3 grains to +.2, Hornady ran -.2 to +.2 and Nosler+.2 with no minus swing.

This is the part of the story where we play find the hidden Weatherby cartridge. Large cartridges are a lot of fun to shoot, lots of noise, cover long distance, and can have extraordinarily flat trajectory with heavy bullets. Unfortunately, the cost per bullet for rounds like the .338-378 is $4.25, or one bullet equals the cost of a box of .223’s.

This is the part of the story where we play find the hidden Weatherby cartridge. Large cartridges are a lot of fun to shoot, lots of noise, cover long distance, and can have extraordinarily flat trajectory with heavy bullets. Unfortunately, the cost per bullet for rounds like the .338-378 is $4.25, or one bullet equals the cost of a box of .223’s.

By the time I’ve reloaded these .223 cartridges 20 times, the cost per box of 20 (with all premium components) will be around $3.60. Decent .223 commercial ammo, Winchester Ballistic Silvertip as an example, runs about $12 per box of 20. Cheapo practice ammo is routinely sold for $5+.

I do believe I have developed a better understanding of one aspect of why people enjoy smaller bore firearms and why they are so popular. They have a great deal of accuracy potential that can be realized with a less than $10,000 custom gun. The cartridges are easy and inexpensive to handload, and offer a very broad range of components to choose from.

Results

There are some things they can’t do with these little guys. Stop a large Cape Buffalo in its tracks, fracture your shoulder as a result of severe recoil, drive people clear of the firing line with a dB reading of 300 – but I guess everything has its tradeoffs.

I have to admit there were some bizarre moments during testing and data recording. I bought this fresh box of low cost Winchester ammo to use as a baseline for the handloads. The average velocity was higher than even the stuffed handloads, 3013 fps, and they left a great deal of powder residue.

I have to admit there were some bizarre moments during testing and data recording. I bought this fresh box of low cost Winchester ammo to use as a baseline for the handloads. The average velocity was higher than even the stuffed handloads, 3013 fps, and they left a great deal of powder residue.

They also generated enough pressure to require assistance for extraction, and jammed the gun’s action to the point I had to remove the barrel to clear the gun. Accuracy was poor.

I’ve used this brand of ammo, on numerous occasions for handgun target practice, with excellent results, so I’m not sure exactly what the problem was. I fired 5 rounds with the exact same results, and none of the handloads, heavily or lightly loaded, caused the same condition.

(This article was written some time ago and, since I still get mail on this issue, I thought I better note the cause of the problem. 5.56mm ammo is loaded to a different specification for maximum average pressure, approximately 8,000 PSI higher, and the brass may be thicker for the .5.56mm and hold less powder. The typical problem of high pressure is caused not so much my a heavier charge or lesser case capacity, but rather because the 5.56mm has a longer leade, unrifled section just ahead of the cartridge chamber, approximately .162″ compared to .085″ for the .223 Remington. Rifles chambered for the .5.56mm can easily handle the .223 Remington round as there is extra room ahead of ammunition assembled to specification. However, ammunition assembled to 5.56 mm specification may force contact with rifling when closing the breech of the firearm, which will result in pressure spike. SAAMI specifies 5.56mm ammo as unsafe for use in firearms chambered for the .223 Remington.)

The Nosler/Winchester Supreme Hunting Bullets were erratic in performance. They held dimensions and weight better than the other two bullets used during checking, but they displayed erratic velocity with all powders and loads, where the other bullets were quite uniform.

The Nosler/Winchester Supreme Hunting Bullets were erratic in performance. They held dimensions and weight better than the other two bullets used during checking, but they displayed erratic velocity with all powders and loads, where the other bullets were quite uniform.

I thought the difference might be attributed to the Winchester Lubalox® coating, but that’s a guess I’m making only because it’s the only visible characteristic differentiating the Nosler bullet from the others. I did disassemble remaining loads and checks powder charge weight, which were verified as indicated on the log sheets.

![]() The max variation within a load was 150 fps, the min was 70 fps. The odd part was, the velocity variation seemed to have no impact on the accuracy within each group. If one powder charge weight / primer combo was accurate for Speer and Hornady, it was also accurate for Nosler, even with the velocity inconsistencies.

The max variation within a load was 150 fps, the min was 70 fps. The odd part was, the velocity variation seemed to have no impact on the accuracy within each group. If one powder charge weight / primer combo was accurate for Speer and Hornady, it was also accurate for Nosler, even with the velocity inconsistencies.

And the wiener is…

|

The handload speed winner

|

|

The handload speed runner up

|

|

The handload accuracy winner

|

When the Contender didn’t like a load, the results weren’t all that subtle. Velocity, not bullets or powder type seemed to determine accuracy. The accuracy load group pictured was shot using three different bullets types and manufacturers, but it didn’t seem to matter. In some other groups, even powder variations of a few tenths shot to the same point of impact and grouped well, if velocity was kept below 2,900 fps.

Conclusion

It was a little disappointing, and maybe a little surprising, to not meet or exceed published velocities for the .223 Contender loads. Surprising because the .223 is such a mature cartridge, and manuals have become so conservative in stating loads and performance results. With best accuracy achieved below 2,900 ft/sec, perhaps this isn’t such a big deal. Working within a 6″ target area, the reduced muzzle velocity results shortened the .223/Contender combination’s effective range by about 50 yards.

| Range Yards | 0 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 200 | 250 |

300 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity ft/s | 2819 | 2600 | 2386 | 2177 | 1974 | 1776 | 1585 |

| Kinetic Energy | 882 | 751 | 632 | 526 | 432 | 350 | 279 |

| Trajectory Inches | -1.0 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 1.3 | -2.7 | -9.3 |

At some point in time, I’ll run some more loads for the Contender .223, using a longer, heavier Berger bullet. This may be a better match to the gun’s rifling, and I’ll concentrate on the powder types that filled the case. Since none of the handloads I’ve covered showed indications of high pressure, I may be able to approach the same 2,900 ft/sec velocity levels with the heavier bullet, and get tight groups.

I know Contenders are very popular with handgun hunters. I don’t believe I would use one on anything larger than very small game, only because I have a difficult time seeing any single shot used for hunting larger animals. I understand an experienced shooter can quickly load a second shot, but I also know I spent a portion of Sunday freeing stuck cases from factory loads the Contender wouldn’t extract.

Contenders are inexpensive to customize, there are lots of accessories available for them, and even nice wood is relatively inexpensive on custom grips and forearms. If handloading is of primary interest, particularly handloading a lot of different cartridges, the Contender is an inexpensive way to build up a long list of cartridges. But ultimately the Contender is a firearm of compromises:

Rifles with longer barrels will always have a higher potential for accuracy

Revolvers, or an X100 repeater will always carry more rounds

High capacity cartridges will not be fully utilized

All that said, I have my Contender and an assortment of barrels and scopes. I’ll write these articles, fire maybe a couple of hundred rounds of a variety of cartridges, and enjoy every moment of it. Then I’ll pack it away for a year or so, until I run across it while I’m digging around for something to do. I’ll handload some more ammo for it, or see another barrel I’d like to try, and……

| More “Revisiting the Thompson Contender”: |

| Revisiting the Thompson Center Contender |

| Revisiting the Thompson Center Contender II |

| Revisiting the Thompson Center Contender III |

Thanks

Joe

21.7 grains IMR 4198

21.7 grains IMR 4198 26.7 grains IMR 4895

26.7 grains IMR 4895

Email Notification